-

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel- NEWS FOCUS

- ABOUT KOREA

- EVENTS

- RESOURCES

- GOVERNMENT

- ABOUT US

"He choked me so hard while thinking of you that from now on things should be okay."

Try to wrap your mind around that sentence. Who's choking who? Who's apologizing to whom, and for what? Between who should things be OK? Insanity is the only refuge for the sane in an insane Escher world.

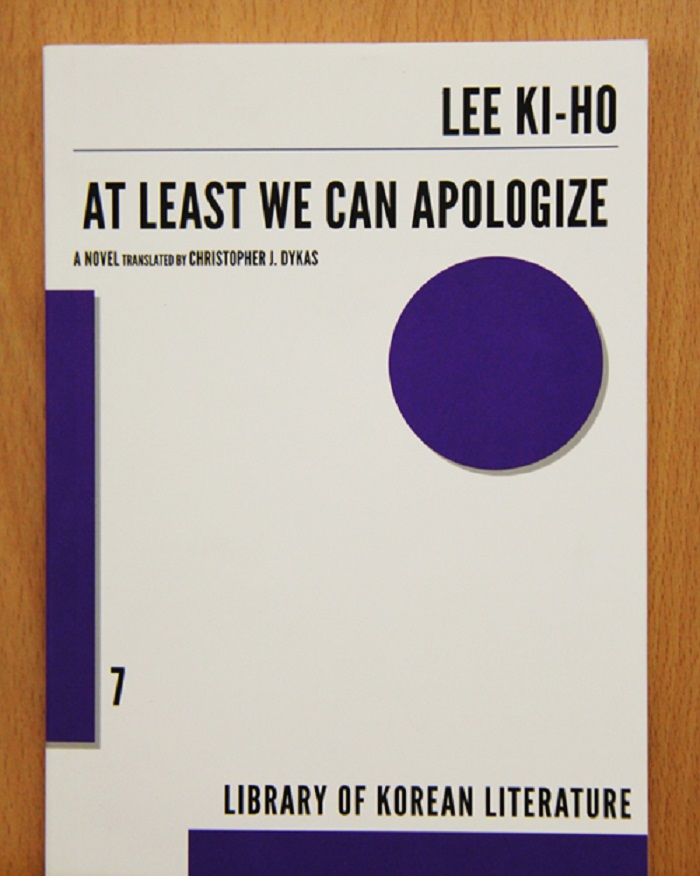

Flying out of far left field like some crazed winged gecko and climbing the padded walls in a white straitjacket, the twisted world of Lee Kiho's "At Least We Can Apologize" ("사과는 잘해요", 2009) hits you like a bucket of cold water. The insanity jumps to the fore from page one, making Hunter S. Thompson or Joseph Heller look almost timid. Lee twists his plot like a lemon in a juicer until a story oozes forth that's part art, part tale and part supernova.

Lee Kiho's 'At Least We Can Apologize' is published in English in 2013 by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea.

Start with the setting. Lee Kiho's Coketown unfolds with the dark asphalt sweat of modern cities. Soviet-style tenement apartment blocks seep into Lee's tale. Humanity is so insane that we live like rats in rectangular cement tenements that reach for the sky and stretch to the horizon. Between the towers lies a sole depressing child's swing set, painted in faded red or pink, in the shadow of the tenement, a tribute to man's idiotic belief that the world is bright. Slogging residents drag their feet up and down a graffitied elevator, convincing themselves that this is a life. As the woman at the corner store says, "Ugh! This dirty neighborhood! I'm sick of all these deadbeats!... This month, I'm outta here... this month!" She's there throughout the novel.

The tale begins a few months earlier at a psychiatric hospital just out of town. There's the superintendent, the director general, the cafeteria woman and the two male caretakers: the shorter one who wears a doctor's gown and the taller one who has a really bad combover. On occasion, government inspectors come to make sure the mental hospital is adhering to national guidelines. On those days, the patients' industrial plastic bed sheets are replaced with cotton bed sheets.

Then there are the patients, euphemistically referred to as "residents," two of whom are the anti-heroes of this tale. They are Si-bong and I, Si-bong and I, Si-bong and I. The story is narrated by Jin-man, but we almost never hear him refer to his own name. You don't even read his name until page 32. It's always, "Si-bong and I," the two Pillars of the Institution.

These two inmates, at this sketchy mental institution, bond through their communal beating: beating after beating. Belt. Boots. Pipe. Fist. Phone book. Shovel to the head. Morning. Day. Night. They're beaten every way possible. They smile and apologize. They're beaten again. Then enters the man with the sideburns.

A scandal erupts in Chapter 1 and so the psychiatric hospital is closed and abandoned, and "Chief" and "McMurphy" are released upon the world. They shack up with Si-bong's sister. Of course she's a small-time prostitute and her deadbeat live-in boyfriend is her pimp and is losing money at the track.

Our two heroes, like Odysseus on his way home, face a series of trials and tribulations as they leave the mental hospital in the early pages and head out into society. First, they have to walk to Si-bong's sister's place: hours walking along the shoulders of rural freeways, and then a bit on a bus. The horse gambling pimp boyfriend takes them out to look for a job. At one point, they head back to the abandoned mental institute to collect uneaten pills, climbing over a cyclone fence along the way. They encounter a Dirt Harpy insane old woman, walk out with pillow cases full of pills and are able to pick up a copy of the superintendent's old diary, too.

Just about to give up on the job hunt, the re-inclusion of formerly prescribed, now free-flowing, medication into their bodies causes them to remember what they're good at: apologizing. They had to apologize for their beatings. They turn this into a small-time business.

Across from the sister's apartment live two squares. Like clowns in a Mozart opera, these buffoons are The Two Men: the Butcher and the Fruit Monger. The Butcher and the Fruit Monger are like Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum, so of course our two mental patients decide to begin apologizing to The Two Men and, like Iago, plant the seeds of jealousy. Our two mental patients plant the seeds of doubt between the Butcher and the Fruit Monger, looking to turn apologizing into a business. Like a quiet gangster building up an extortion racket from small-time store owners, our two heroes progress. As in "Asterix and the Soothsayer", chaos erupts. Fights break out. Our two heroes now have a thriving business on their hands. The story progresses.

Novelist Lee Kiho is at the vanguard of modern Korean literature.

Literature as social commentary

Author Lee Kiho's world is distraught. As the twists and tears of modern Korea's social fabric are being catapulted into the future, the past's romanticized centuries of honorable nobility are leaving people ill-equipped to face a globalized world. There are only elements of honorable behavior remaining in today's society.

Broadly, Lee Kiho's world has been eviscerated through a colonial imperialist grinder for some 50 odd years, and then doubly-eviscerated through a similar series of militarized dictatorship grinders for another 50 some odd years, removing any honorable behavior. Emerging, shocked, like Si-bong and I, into the 21st century, Korea's wounds bleed openly, and it is the novelists, writers and poets who offer a soothing balm to our painful scars.

To see a truly human Korea, however, you must read literature. Read, read and read more. If you want to see humans as being truly human, not as some plastic pastiche read Korean literature. Read Korean literature and this nation becomes truly alive. Read Korean literature and this place becomes so much more cool. Psy would approve.

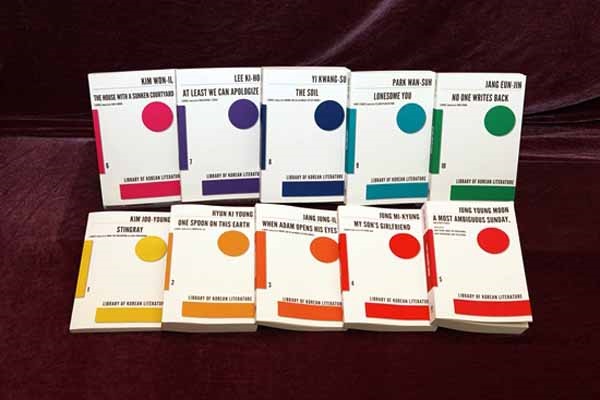

Leading this vanguard of modern Korean literature is Lee Kiho (이기호). He turns 44 this year and lives in Gwangju, South Jeolla Province. His pen must be possessed by a jack rabbit, as his chapters jump back and forth between flashback and the present. Like scenes from "Pulp Fiction", the reader has to piece it all together. It unfolds at a proper pace, however, with no bumps or jilts. Readers are never lost. He uses short sentences, short chapters and even some short mini-chapters. This edition is part of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea's "Library of Korean Literature" and was translated in 2013 into English by Christopher Dykas. Lee Kiho weaves a tale of sanity in an insane world: extorting money from you for apologizing to someone else for something you didn't do. As it progresses, we, ourselves, slowly climb the padded wall in our white straight jacket.

The Library of Korean Literature is put out by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea.

"After we confessed a wrong, we always made sure to commit it. That was on account of our feeling unsettled after having the confession in our heads all day long."

Corporal punishment

To a modern Western reader, the sheer physicality of Lee Kiho's world can be a shock. Physical barbarity seeps through the paragraphs like sweat through a rag.

So corporal punishment, though on the way out, is all over the modern Korean psyche and is all over Lee Kiho's "At Least We Can Apologize."

Si-bong and I are beaten all the time. Each flash back has the two main characters being beaten. Lee Kiho's creepiness as an author comes about quite clearly: Si-bong and I smile as we're beaten. Our two heroes, who go on to sell the act of apologizing, bear physical punishment worse than "Fight Club", worse than some torture scenes. They smile and apologize.

Lee Kiho finishes many of his chapters like this: "That was on account of that being all there was to say." The beatings and the apologies say it all.

Small shafts of light & Pulling yourself up by your bootstraps

There is light in Lee Kiho's otherwise dystopian world. The main characters, all dregs and bilge water of the world, can develop hearts of gold and do have human emotions. To see it, however, you'll have to read the middle third of the novel. That third-of-a-book is an amazing breath of fresh air... until the shock hits you. Lee Kiho never relents.

As Charlie Kaufman once said in one of his screenplays, "The last act makes a film. Wow them in the end, and you got a hit. You can have flaws, problems, but wow them in the end, and you've got a hit. Find an ending, but don't cheat, and don't you dare bring in a deus ex machina. Your characters must change, and the change must come from them. Do that and you'll be fine."

Well, Lee Kiho is fine. He's just fine.

It was a pitch black night

To share but a taste of Lee Kiho's dystopian world, we can conclude with a short recollection from early on in "At Least We Can Apologize".

Si-bong says: "A long time ago I was in a taxi and I had to go to the bathroom." He was scratching his head as he spoke. "So the taxi pulled over and I squatted down right in the ditch by the side of the road to take care of my business, but when I got up, the taxi was gone."

"Wow... it just left you there and drove off?"

"No. It ended up underneath a semi. It was a pitch black night."

by Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Literature Translation Institute of Korea, Yonhap News

gceaves@korea.kr