-

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel- NEWS FOCUS

- ABOUT KOREA

- EVENTS

- RESOURCES

- GOVERNMENT

- ABOUT US

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

|

Monthly Korea’s Jan. 2020 issue. ▶Link to Webzine |

Durable, Eco-friendly Homes

A daemokjang is a master carpenter who assumes full responsibility for the design and construction of traditional Korean structures such as Hanok (traditional Korean home), starting with the selection of timber. Just three daemokjang remain in Korea, and one of them is Choi Gi-young. He has received the designation of intangible cultural heritage by the Korean government for his contributions to numerous restoration projects for historical Buddhist temples.

Written by Kim You-rim / Photographed by Studio Kenn

The start of Choi Gi-young’s life was far from comfortable. He was born in 1945 after Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule, and five years later, the country was devastated by the Korean War. His father died when Choi was 5 and his family soon fell into abject poverty. He barely graduated from elementary school as he had to collect firewood from the mountains and cut grass on the fields every day. Choi, however, spared time to attend a seodang (Confucian academy) for basic education in Chinese classics ranging from The Cheonjamun (Thousand Character Classic), used as a primer for teaching Chinese characters, to The Book of Mencius, which helped him study traditional Korean architecture later. He decided to become a carpenter after learning that the son of his seodang teacher who pursued that trade had a stable occupation, thus valuing security more than anything else at the time.

“I had no lofty reason for wanting to become a carpenter. I wanted to gain the skills to survive. I learned carpentry to feed myself. While learning carpentry, I found myself a bit ahead of others in talent and worked hard. That made me what I am today. I’ve experienced everything you can imagine in my life, but never considered quitting carpentry,” he said.

Passion-led Development

This is a tool that master Hanok carpenter Choi Gi-young has used for a long time.

Choi said he has never slept more than four hours a day since childhood. Though he lucked out in meeting master carpenters Kim Deok-hee and Kim Chung-hee, his outstanding dexterity and sharp eyes were a testament to his extraordinary skills. His hands did exactly what he was shown or told, he said, and he quickly familiarized himself with any new tool. Korea at the time had no carpentry textbooks, let alone one-on-one training for vocational skill development. He watched his teachers working on their pieces, but his natural talent did not remain hidden for long. Choi later heard from his mother that not only his father but also his grandfather had been a carpenter. As the old saying goes, the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree. With his mentors, Choi crisscrossed the country to work on major landmarks from Woljeongsa Temple in Pyeongchang-gun County, Gangwon-do Province, to Deoksugung Palace in Seoul. In the evening, his teachers drew architectural drawings on Hanji (traditional handmade Korean paper), a scene that captivated the young apprentice and eventually drove him to sneak out of bed and go over the fences of royal palaces at night many times. Pointing a flashlight at eaves and pillars, he memorized every detail of the structure he was to work on; when he had no flashlight, he drew every detail on scraps of paper under the moonlight.

“If you learn things the ordinary way, you’ll become just an ordinary carpenter. When I began to learn carpentry, there were 50 of us, and just a few became master carpenters who worked while the others were sleeping. They kept thinking about their work, made numerous drawings, delved into structural factors and even dreamed about their work at night. A master carpenter considers the lifestyle of the owner of a potential building he or she will build, thus pays keen attention to every detail possible including the height and width of spaces in a given structure as well as the size of columns,” Choi said.

Achieving Fame

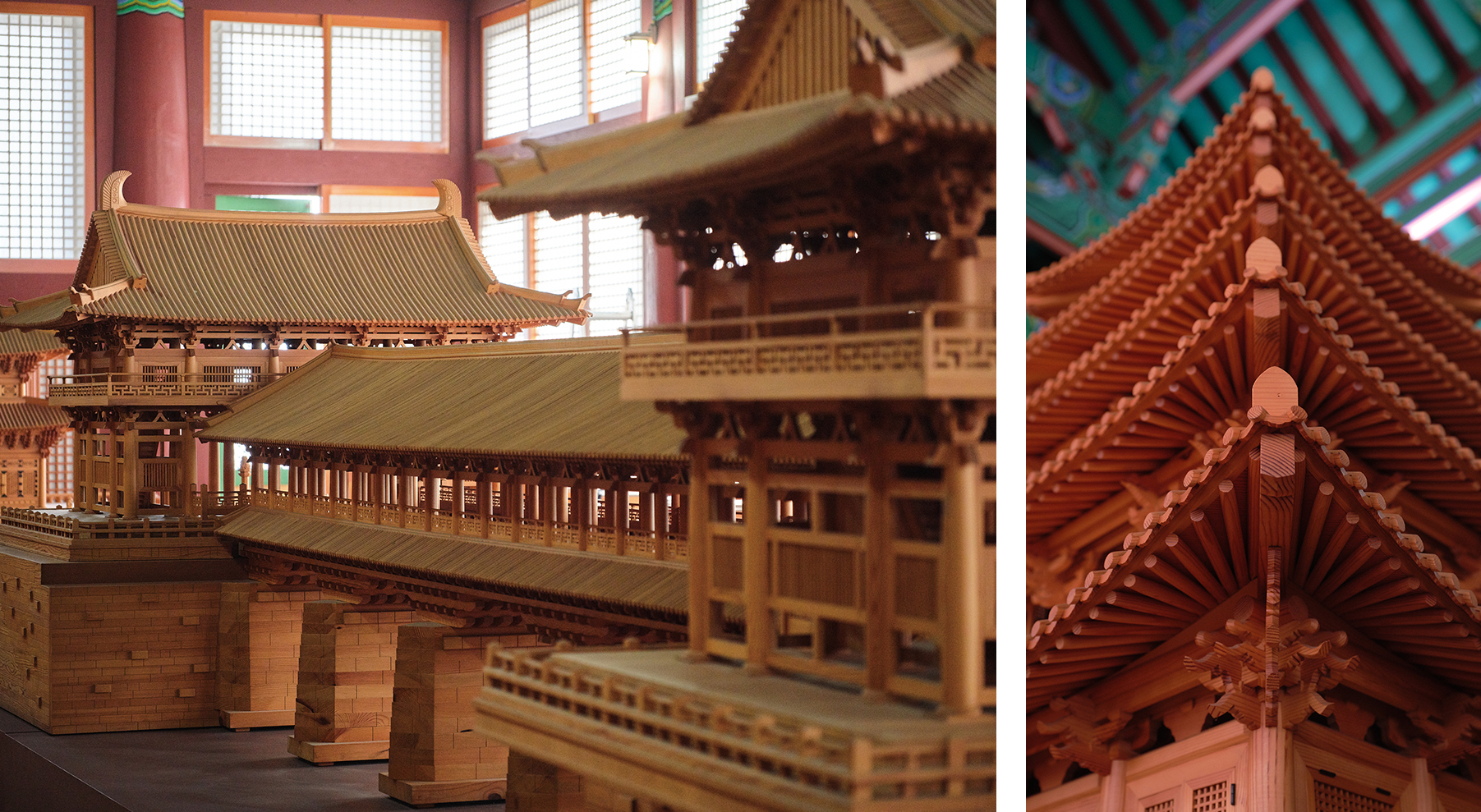

Miniature replicas of Geunjeongjeon Hall of Gyeongbokgung Palace and Woljeonggyo Bridge in Gyeongju, Chungcheongbuk-do Province, both built by Choi Gi-young, greatly help those trying to understand Hanok structure.

Geungnakjeon Hall at Bongjeongsa Temple in Andong, Gyeongsangbuk-do Province, was built around 1200, and as National Treasure No. 15, it is the oldest surviving wooden building in Korea. Choi dismantled, repaired and reassembled this building, and the cold of winter did not deter him from resting. Rather, the season is perfect for building a Hanok with cold winds blowing and low humidity. Previous master builders used to work with their favorite students throughout the winter from late October.

Civil engineering works began before the ground froze, and work on the base was done on the cornerstones before winter began. In winter, wood was trimmed and dried simultaneously, as it was essential to assemble timber before March and lay roof tiles prior to the rainy season. The best time for finishing plaster work was before and after Chuseok. Around that time, the early morning dew permeated the walls and the drying process was repeated by day, resulting in less cracking than in walls plastered in other seasons.

“Hanok built from nature can last a thousand years alongside people. How is that possible? First, all of (Hanok’s) materials come from nature. Second, it is built by carpenters who abide by principles and fundamentals. Korean pine, soil, stones, tiles and window paper are all from nature. Even if they are chopped and cut, they are alive and continue to breathe. Tiles breathe. Pinewood keeps breathing. Its blood — pine resin — continues to flow. In a Hanok, you can hear the house breathe just as nature breathes. Of course over time, even the best-built Hanok can develop cracks in its earthen walls and wood. Yet if you live in and take care of it, Hanok can last for a thousand years without much difficulty and your descendants can cherish it for numerous generations,” he said.

The carpenter scrutinizes thick hardwood to be used for building a Hanok.