On that same day, the two governments also signed the Agreement on the Settlement of Problems Concerning Property & Claims and on Economic Cooperation.

Clause 1 of Article II of that agreement says, "The contracting parties confirm that the problem concerning properties, rights and interests of the two contracting parties and their nationals, including juridical persons, and concerning claims between the contracting parties and their nationals, including those provided for in Article IV, paragraph (a) of the Treaty of Peace with Japan signed in the city of San Francisco on September 8, 1951, is settled completely and finally."

The clause above has been grounds for Japan's claim that every bilateral problem between the two governments, including the so-called "comfort women" issue, has been settled. Korea, on the other hand, continues to claim that the clause does not cover the "comfort women" issue and that this issue and others have not been settled. As seen with their differences over these issues, the Korea-Japan Agreement signed in 1965 has been the target of broad criticism, even though it marked the official resumption of diplomatic ties between the two neighbors. Some say that the agreement is "humiliating" and was "hasty, with no caution." Others say the agreement should be amended or that even the two governments should sign a new agreement.

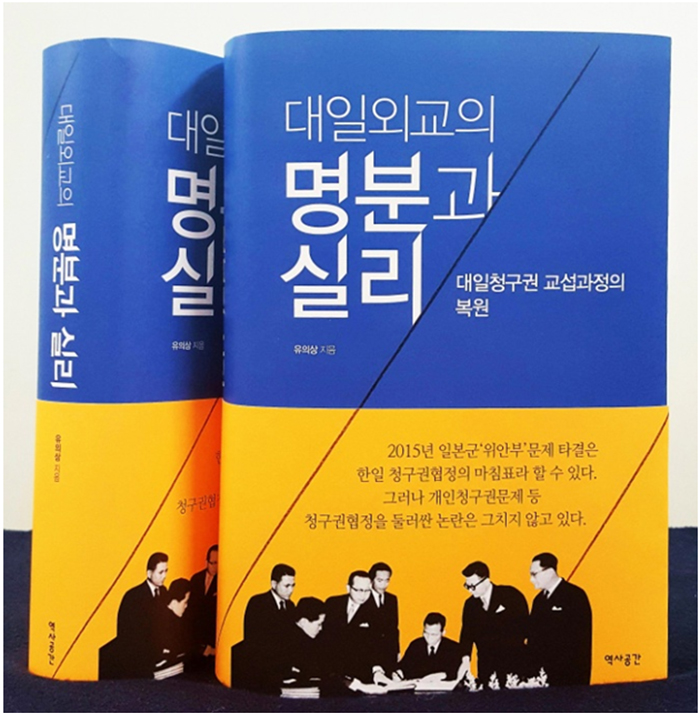

Against this stream of criticism, a new book has been recently published that sees the agreement as a great achievement of Korean diplomacy. "Diplomatic Propriety & Our Interests With Japan" (대일외교의 명분과 실리) was written by Ambassador-at-large for Geographic Naming Yoo Euy-sang, currently at the Northeast Asian History Foundation. The author is a professional diplomat who has been working for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs since 1981, with years of experience at the Korean Embassy in Japan as both the second and first secretary, and at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs as director of Northeast Asia Division 1.

In his book, the diplomat meticulously reviews the entire process of bilateral meetings that were required to reach the agreement. He says, "The 'comfort women' issue was never discussed as one of the major agenda items during the meetings," and that, "Japan's claim that the issue has been settled in accordance with the agreement is an arbitrary interpretation that is not correct."

Korea.net recently sat down with Yoo and heard from him about explaining and outlining the complicated puzzle that is the 1965 Korea-Japan agreement.

Yoo Euy-sang, diplomat and author of 'Diplomatic Propriety & Our Interests With Japan,' says that the 1965 Korea-Japan agreement is a significant moment in the diplomatic history of Korea, and that it should be comprehensively re-estimated considering all the factors. These include the political background at the time, the other party's interpretation of history, its willingness for meetings, third party intervention, Korea's then very weak diplomatic infrastructure and Korea's economic status at the time.

- Issues between Seoul and Tokyo are like a heavy, tangled skein of thread. Your book, though, seems to have succeeded well in explaining such difficult material, both chronologically and logically. What made you write this book?

As I wrote in my foreword, diplomatic relations with Japan don't only include Tokyo, but also include Korean domestic media and Korean non-governmental organizations. Dealing with Tokyo takes only, let's say, 30 percent out of 100, and the rest is dealing with domestic public sentiment.

Issues related to the colonial past are really complicated. Once they're on the table, talking about the 1965 Korea-Japan agreement is inevitable.

Working in this field, I instinctively knew that reaching the agreement must've been extremely difficult. Despite my access to records, reading the entire set of records about the agreement wasn't easy while holding down a full-time job. Indeed, I often felt my lack of knowledge when I had to sit down with some NGO and explain the agreement to them, which made me decide to read through the entire records at some point.

More direct motivation came in 2003 and 2004 when I had to appear in court as a witness for the government in a case asking for the disclosure of certain records concerning the agreement. Though the government might have lacked consistency, it never lied to its nationals. Still, people easily assumed that the government was fooling them.

About a year later, the government decided to release the records and pretty much all of such assumptions have been proven wrong. No one, however, commented about the false accusations or even about the record itself. It's not easy to read through all the primary sources, I understand, but even academics said nothing about it. That's when I decided I would do it. I collected the sources for my research from all the records released by the Korean government in 2005, and more from the records partly disclosed by the Japanese government in response to non-government organizations' requests.

A pragmatic point of view and an understanding of history is required to analyze and re-estimate the 1965 Korea-Japan agreement, says Yoo.

- Seventy years have passed since the end of colonialism, yet resentment or rage has become somewhat stronger. As disagreements over the colonial past have worsened, it has fueled emotional conflicts. Also, the fervor for Korean pop culture in Japan has also diminished. It's a bit of an exaggeration, but the two nations have never seen so much disagreement on any matter, ever since the invasions of Korea in the 1590s. What are the problems do you think?

The Korea-Japan relationship is like a series of hills and valleys. It has always had some ups and downs, ever since Korea's independence in 1945. During the Rhee Syngman administration, anti-Japan sentiment was dominant nationwide, and reconciliation between the two wasn't even imaginable. This means that the Seoul-Tokyo meetings during the Rhee administration were unproductive. The two reached an agreement and re-established diplomatic ties under the Park Chung-hee administration, but what happened after the agreement is more important.

In 1973 when Kim Dae-jung was kidnapped in Tokyo, the bilateral relationship was bad. In January 1998, during the Kim Young-sam administration, when Japan broke the fisheries agreement, the relationship worsened again. This then led Japan to even withdraw all of its short-term funds that had been invested in Korea due to the so-called "IMF crisis." The bilateral relationship has repeated this pattern of good and bad. That means that this recent discord is nothing particularly new.

Nonetheless, there are certain aspects that can be seen as new. In the past, positive efforts would soon follow as soon as the relationship worsened. There were politicians who could communicate with Japan in Japanese due to legacies from the colonial period, which is not the proudest thing to say. Politicians like former Prime Minister Kim Jong-pil is one of them. Those people moved quickly and spoke with the people in power behind the curtain in Tokyo to ease the worsened relationship.

'Diplomatic Propriety & Our Interests With Japan' is written by Yoo Eui-sang and recalls the entire process of reaching the 1965 Korea-Japan agreement. It's based on primary sources and declassified records from the two governments.

- The "comfort women" issue was mentioned during the administration of former President Lee Myung-bak, too, I believe.

Most of the former Korean administrations have shown certain patterns in their relationship with Japan. They tend to maintain a good relationship at the beginning of their term in office and closer to the end of their term, the relationship worsens. Things like a president's visit to Dokdo Island or a comment aimed at the Japanese monarch can worsen the relationship, and then the "comfort women" issue has been shifted over to this administration.

One thing is, though, that the issue used to be just one of the many challenging tasks between the two nations. Now, it has become one of the most serious, important priorities. This may have triggered some embarrassment or confusion.

Academics analyze the background of the recent discord in various ways. First of all, the current Japanese administration is the conservative Abe cabinet. No, this is not the first time that Japan has had a conservative cabinet. However, in the past, politicians with a good understanding of each other were able to sit down and talk "under the water." There are no such politicians nowadays. The Federation of Korea-Japan Politicians doesn't play its role anymore. In the past, there was no language barrier, even though that's not something of which to be proud, and it was easier for politicians to talk to each other. Nowadays, however, Korean politicians who speak Japanese are nowhere to be seen. In short, the communication bridge has collapsed, which means it's now up to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, but the ministry doesn't really have any people who are that specialized in Japan anymore.

Another reason is structural change. In the past, Japan in some ways stepped back from Korea and gave it some space, in what was called a "strategic tolerance" policy. The nation had no problem being tolerant of Korea. Twenty years of economic depression, however, have caused Japan to no longer be tolerant. In addition, Korea has nearly kept up with them. Japan now has no reason anymore to be tolerant of Korea. This was, in fact, mentioned in an interview with a former Japanese foreign affairs minister recently in a financial newspaper.

In the meantime, recession also encourages nationalism and populism in Japan. In the past, most Japanese newspapers were politically balanced, except for a few papers. Now, however, there's barely any balance. The daily Yomiuri newspaper publishes serialized articles condemning Korea, and even the neutral Mainichi Daily News has now changed, not to mention the Sankei daily newspaper. This change in newspaper voice has consolidated Japanese public sentiment, which works as an obstacle to easing our relationship.

The 1965 Korea-Japan agreement, though not perfect, still contains many achievements that can be seen positively by both history and by people today, Yoo believes.

- Let's get into your book. Intellectuals and students criticize the 1965 agreement. Historians don't see it positively. Some, meanwhile, say that the fifty years since the agreement have been "deserved blessings." You insist that there is great value in the agreement. Why is that?

The 1965 agreement surely has aspects that could be criticized. First of all, it didn't succeed in achieving its initial goal, to settle all the problems related to the colonial past, and down to today we still argue about those problems. Second, the Korean government took away its citizens' individual rights to ask for reparations from the Japanese government as victims of colonialism. The Korean government made a lump sum agreement concerning this matter.

I believe, however, that history, especially diplomacy, should be seen from a comprehensive point of view, considering all the factors and backgrounds that are involved. For example, look at the other party's character, the conditions the two parties were facing, any pressure from a third party, et cetera. I think that assuming some premise to begin with, and then using the values and standards of our time to look at history in a narrow manner, just isn't right. That's why I've explained in this book why the 1965 agreement should not be re-evaluated based on today's thinking or frame of mind.

First, there were only 30 people in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs when we first met with Japan in the 1950s. Our Japanese counterpart had a staff of about 1,000. As of the end of 2015, our staff at the ministry number around 2,200, and the figure at the Japanese ministry is about 5,800.

In addition, Japan was once an empire. An empire has a great many people skilled in the art of diplomacy and negotiations, as it has to run and manage other countries. We, as non-professionals, sat down to negotiate with that staff fully loaded with years of accumulated diplomatic knowledge and experience.

Another thing to know when looking at the 1965 agreement is how the Korea-Japan meetings began. At first, Korea asked for reparations from Japan for the victims and damages from colonial times. However, Korea couldn't talk directly with Japan, as Japan was under U.S. occupation. As a consequence, Korea had to talk through an international channel, the Peace Treaty of San Francisco signed in 1951.

The Korean government made every effort to participate in those meetings as one of the parties, but didn't succeed. There're several reasons as to why, but the principal reason was that Korea strongly claimed that reparations were against the interests of the U.S. Initially, the U.S. wanted China to be its Northeast Asian ally, while keeping Japan, its enemy during the Pacific War, far away from revival. China, however, became a communist country.

With an international situation where half of Europe was turning communist, the wave of communism was now coming to Northeast Asia. The U.S. wanted a Northeast Asian agent, and the only potential was Japan.

Against this backdrop, the Korean government, asking strongly for reparations from Japan, was excluded from the San Francisco meetings. Still, the Rhee administration didn't give up and was able to include one paragraph into the San Francisco treaty. It prescribed that any matters related to reparations could be discussed through a "special arrangement." According to Article 4, paragraph (a) of the Peace Treaty of San Francisco, "subject to the provisions of paragraph (b) of this Article, the disposition of property of Japan and of its nationals in the areas referred to in Article 2, and their claims, including debts, against the authorities presently administering such areas, and the residents (including juridical persons) thereof, and the disposition in Japan of property of such authorities and residents, and of claims, including debts, of such authorities and residents against Japan and its nationals, shall be the subject of special arrangements between Japan and such authorities. The property of any of the Allied Powers or its nationals in the areas referred to in Article 2 shall, insofar as this has not already been done, be returned by the administering authority in the condition in which it now exists. (The term nationals whenever used in the present Treaty includes juridical persons.)" This was the basis through which Seoul was later able to hold meetings with Tokyo.

According to paragraph (b) of the same article, "Japan recognizes the validity of dispositions of property of Japan and Japanese nationals made by or pursuant to directives of the United States Military Government in any of the areas referred to in Articles 2 and 3." This was also included in the Seoul government's request. In short, the Korea-Japan meetings were arranged by the U.S. and this bound Korea to not ask for reparations.

The basic idea behind the first Korea-Japan meetings was simply about Japan giving up its claims to property left in Korea, and about Korea giving up its right to ask for reparations from Japan, with a little bit extra that Korea was eligible to receive. Korea, however, eventually ended up getting USD 500 million from Japan after a series of meetings. Japan's holdings at that time were about USD 1.6 billion. The roughly USD 500 million, though it took 10 years to get, is an achievement that is valuable enough.

Finally, Japan had no shame about or willingness to apologize about colonization. In fact, other empires have been no different from Japan. This is why there was no legal post-war reparations for the victims. Nonetheless, Korea reached an agreement. Is this still something to be criticized? This is what I wanted to say in this book.

There're no win-lose scenarios in diplomacy, only win-win. Yoo praises Seoul's diplomatic successes in 1965, earned under a difficult domestic and international situation.

The "comfort women" issue is very complicated. In the past, Korea only asked for an apology from the Japanese government, claiming that the Korean government would give reparations to those victims. The Liberal Democratic Party of Japan also once showed some shame about its country's past, and former Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama of a coalition government was from the Social Democratic Party. The Murayama Statement announced in 1995 and the Asian Women's Fund were all part of this political trend in Japan, though the Seoul government rejected the funds as it wasn't what the victims wanted.

What's important here was that the Tokyo government admits its legal responsibility to the victims and pay them reparations. The funds were rejected because they didn't include the Japanese government's admission of responsibility. Meanwhile, Japan raised objections that there were some victims who accepted the funds, and, in fact, seven people did accept the funds at first.

The Seoul government later paid KRW 43 million per person: KRW 5 million from the Kim Young-sam administration and KRW 38 million from the Kim Dae-jung administration. The KRW 38 million consisted of KRW 6.5 million from the government, and KRW 31.5 million from public donations. The original number of victims eligible to receive reparations at that time was about 150, and is now about 238 people. Eligible victims registered on the list later got paid their entire amount at once, in full. At present, the victims are paid KRW 1.2 million per month, and receive free housing and medical services. Local governments also distribute to them a stipend of between KRW 500 thousand and KRW 1 million.

- The diplomats who negotiated with their Japanese counterparts were mostly in their 30s and 40s in the 1950s and 1960s. The results of their meetings seem to be quite an achievement, given Seoul's lack of human resources specialized in international law and diplomatic negotiation.

During the Rhee administration, the president gave every order concerning every single matter. A former congressman once called Rhee the "god of diplomacy." Though the former president and his work is controversial, I agree that he, indeed, had great diplomatic insight.

Yang Yu-chan, the chief delegate at the preliminary, first and second meetings, was a former obstetrician who spoke fluent English and who didn't speak Japanese at all. Rhee appointed Yang, who, as I said, didn't speak Japanese, on purpose and encouraged him to focus only on talking to the U.S.

The second delegate, Kim Yong-shik, though, spoke both English and Japanese fluently. Rhee liked this and planned and gave directions on every single little detail. During the ten years of the Rhee administration, true diplomats were developed. Kim Dong-jo, who later became the chief ambassador during the signing in 1965, played a key role during this time. From the fifth meeting, under the Chang Myon administration, professional diplomats and practitioners joined in, and this was when the real diplomatic negotiations began.

- As you mentioned earlier, Japan has no shame about its colonization, and Japan, in fact, is no different from other empires. Japan these days is often contrasted with Germany because the European country has admitted shame about its past, but Japan hasn't. Also, Germany doesn't seem to be too strict about the punishment of war criminals.

That's exactly what Japan claims. In Germany, the Nazi Party, the subject of all the war crimes, is extinct and that's why later generations did and are able to criticize the nation's past. In Japan, on the other hand, the monarch still remains on his throne. General Douglas MacArthur insisted that the Japanese monarch should retain the throne and be the "spiritual leader" that would allow Japan to rise again.

Another difference between Germany and Japan is that the former went through social struggles, such as division and reunion. In other words, the nation had a chance to look back on its past.

Japan, meanwhile, had no such chances. The Liberal Democratic Party has been ruling Japan since 1955, except for one very short moment. There has been no atmosphere of looking back on the past. This is in contrast to Germany, whose current chancellor is actually from East Germany.

- What lessons could we learn from the Korea-Japan meetings and from the 1965 agreement?

The fundamental element of negotiation is the existence of another party. This is not a game where only one party can win, like with a binary score of either 100 or 0. Compromise is inevitable. This is why negotiations should not be measured by a standard frame of mind or by any moral principles. No matter how unsatisfactory the results, any achievement, if made, should be seen objectively. This is the lesson I want to deliver through my book.

By Wi Tack-whan, Chang Iou-chung

Korea.net Staff Writers

Photos: Jeon Han

whan23@korea.kr

Most popular

- APEC Economies Gather in Incheon to Advance Tourism Cooperation through Innovation and Sustainability

- Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Holds First Digital & AI Ministerial Meeting (DMM)

- Authorities Propose Plans to Set Up Anti-vishing Platform Using Artificial Intelligence Analytics

- Campaign Launched to Correct National Heritage Errors in ChatGPT

- Learning from Korea, the Best Practice Country in Pandemic Preparedness and Response