View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

*This is the second part in our series, “Gat, traditional headgear in Korea.”

The development of the gat over time: Changes in dress codes and hats

In terms of headgear, the representative hat for Joseon-era men was the gat, whose socio-cultural context far surpasses the dictionary definition of the term. The development of the gat has implications not only with regard to the influence of Confucianism during the Joseon period (1392-1910), but also by representing the development of indigenous headwear in Korea. As can be imagined, a diverse range of gat existed during the 500 plus years of the Joseon period. There was the paeraengi, the chorip, the heukrip, the baekrip, the jurip, the okrorip, the jeonrip, the bangnip and the sakkat, for example, all to be worn according to one’s social status and depending on the occasion. In particular, the heukrip was the foremost exemplar of Joseon-era headgear, as it was the representative official hat over the five centuries of the Yi Dynasty’s reign. To date, it remains in use for ceremonial purposes.

The term heukrip can be found in use as early as 1367, the 16th year of King Gongmin’s reign (r. 1351-1374) during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). The word originated from the production of heukrip decorated with jewelry befitting one’s governmental status. The heukrip prevalent at this time, however, differed from those used later in the Joseon period, and the hat-top decorations on Goryeo-era heukrip allow the speculation that they may have been closer in origin to the balip of the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), established by Kublai Khan. The shape of the heukrip was finalized during the Joseon era, and soon became the hat of choice for the upper class.

Over time, the aesthetic sense of the time shifted, restrictions based on social class were lightened and gat began to be worn by ordinary citizens and by low-level officials. Changes in gat fashion changed, too, alongside such trends. In terms of appearance, the popular hat went through changes in shape, size and brim width, as well as in the materials used in production and in the decorations. Such alterations are evident not only from ancient documents regarding the restrictions placed upon social status, but also from existing paintings and artifacts. According to the Gyeongguk Daejeon, the complete codification of Korean law from Goryeo (918-1392) to Joseon (1392-1910) and published in 1485, officials from the first rank to the third rank were to use silver for the embroidery of their hats, while royal families, including the daegun himself, were permitted to use gold. Hat-top decorations made of jade were permitted for officials in the administrative divisions of the saheonbu, the branch that oversaw the government, the saganwon, the branch that oversaw the monarchy, and the jeoldosa, the military chiefs. Finally, government inspectors wore crystals on top of their hats. This would suggest that the late Goryeo-era policy of wearing decorated heukrip was in place at least by the time of King Seongjong (r. 1469-1494), during the early Joseon era.

Although the precise form of early Joseon gat is indeterminable, records exist regarding the gat, the heukrip, the gojeonglip, the jungnip and the chorip. The shape of the gat was first discussed during the reign of King Seongjeong (r. 1469-1494), when it was name the ibche wonjeong-I cheomgwang, meaning that it had “a round top and a broad brim.” It was decreed that all gat would be produced following this format.

It would appear that following King Seongjong, the gat neared its stage of completion. From the hemispherical crown and broad brim of the balip, the gat was altered to have a more cylindrical crown with a narrow top and a broader base, and was produced using a more diverse range of materials. Having undergone phases such as the pyeongnyangja and chorip, headgear in Korea culminated in the heukrip, which is representative of the Joseon period.

The heukrip is made by attaching the yangtae, or brim, to the daewu, or crown, wherein the former is somewhat curved at the rim, while the latter is cylindrical and broader at the base with a flat peak. The crown and brim are meshed using fine bamboo threads cut to a hair’s breadth, and the heurip is completed with a black lacquer finish. The hat was considered a part of comfortable dress, mainly worn by the gentry in their daily lives. It was an indigenous invention of the Joseon people, with sartorial influences from neighboring kingdoms, and saw widespread use until the latter days of the Yi family’s reign. Despite the popularity of the black style, different occasions required the use of different colors; for example, the red-lacquered jurip was worn as part of the uniform for a military dangsanggwan, or senior official, while the white baekrip was worn on occasions of national mourning.

While in some cases, only bamboo threads were used for the hat crown and brim, some used horsehair for the crown. Further distinctions can be made through the cover enveloping the crown and brim. Dependinon the material and method of production, the heukrip can be subdivided into categories such as the jinsarip, the eumyangsarip, the eumyangrip, the mamirip and the porip.

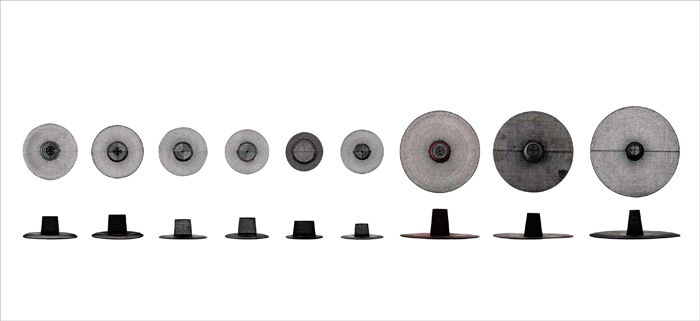

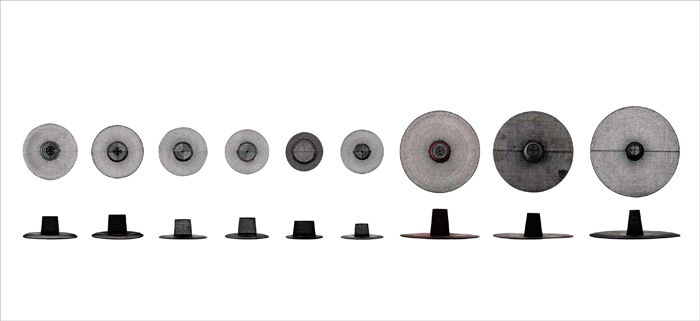

From the chronology of changes made to the gat, it is evident that the headgear was initially round at the crown with a broad rim and that the crown became gradually higher and the rim remained broad. During the reign of King Myeongjong (r. 1545-1567), the crown was excessively low, to the point of resembling a small plate atop a larger plate, while the brim resembled a small umbrella. This trend was mocked for its similarity to the hat worn by monks, the seungnip. The variation created to compensate for this shape was, in turn, ridiculed for its disproportionately high crown and narrow brim. Alterations such as these show the effect of fashion trends of the period on the development of headgear.

Indeed, the gat of the early 16th century, toward the end of the Yeonsangun’s reign (r. 1494-1506), showed many changes regarding the height of the crown and the width of the brim. Headgear policy during the reign of King Jungjong (r. 1506-1544) was variable to the point of frivolity. The gat of this period began with a tall crown and a wide brim, but toward the end of this period, when the hat had become even higher while the brim became narrower. King Myeongjong’s reign saw the crown lowered and the brim broadened again.

Subsequently, complaints were made during King Hyojong’s time on the throne (r. 1649-1659) that the gat brim was too wide, to the point of being caught on doorframes. In contrast, King Sukjong (r. 1674-1720) saw that both the crown and the brim were reduced to an extent that caused controversy, as it was said to be in violation of past policy.

Critic Yi Deok-mu wrote that, “The hat-brims of olden days could barely cover the shoulders, but now, they are too broad and take up more space than a person covers when sitting cross-legged. At present, the design of the gat is deplorable and strange, being neither aesthetically pleasing nor easy to use. The excessive size errs on the side of extravagance and wastefulness, and there is a dire need to instigate regulations and discontinue this already-familiar custom in order to resist further negative repercussions.”

Yi Deok-mu blamed the arrogant conduct of the nobility entirely upon the gat. He felt the translucent headgear could neither provide shelter form the rain nor from the sunlight and yet the reverence that men had for their gat was exceptional. The gat was an ornate affair, not only with regard to the body of the hat but also to the chin strap (gakkeun). According to the Gyeongguk Daejeon, a code of law promulgated in 1485 that dictated one’s behavior, clothes and other local ordinances, only officials above the level of dangsanggwan were permitted to use gold and jape on their chin strap, while the lower-leveled danghagwan were prohibited from using agate, amber, coral or lapis lazuli. The social disorder and instability of the legal system at the time led to the emergence of the class-based regulation when one’s gat strap became a social issue.

Furthermore, the gat straps used by the nobility were comprised of beads made from ivory, agate and bamboo, of such a length that some drooped down below the waist. Some examples have been found of a lengthy gat strap curled around the ears. Changes were also seen in gat straps, such as the use of silk thread. During one of King Yeongjo’s (r. 1724-1776) sojourns at a hot springs in Gwacheon-hyeon, silk thread was first used along with previous stones for the gat strap.

The competition over the size of the gat and the lavishness of the strap was not only the culmination of the nobility’s desire to display their wealth, but also the somewhat more subtle show of the availability of leisure time necessary for dressing properly. Such pursuits became the measure upon which the nobility compared each other’s fashion and elegant taste.

Through King Seonjo’s reign (r. 1567-1608), the height of the crown was raised to around eight chi (24.314cm, 1 chi= 3.03cm), with a narrower brim. This trend was reversed in the Gwanghaegun’s reign (r. 1608-1623). Records from King Injo’s reign (r. 1623-1649) indicate that, “following the years of gyemi [1643] and gapsin [1644], the gat crown was suddenly made taller and larger, with the brim following suit, to become much broader.” Minutes from discussions regarding official dress policy during Hyojong’s reign (r. 1649-1659) document the complaint that the crown and the brim of the gat have become too tall and wide, and have become a hindrance when entering doorways. At this time, the height of the crown was set at four chi and five pun (13.5cm) using a pobaekcheok, a special ruler used for measuring items of clothing.

Around the time of King Yeongjo’s reign (r. 1724-1776) in the 18th century, the crown’s height was raised and the brim broadened once again. As apparent from the cultural remains from the period, the gat of Yeongjo and Jeongjo’s reigns (1724-1776 and 1776-1800) had relatively wide brims, while the straps made of materials such as cloudy amber, amber and turtle shell, added to the glamour.

In the late Joseon period, the range of robes became more diverse, with variants such as the dopo, the jungchimak, the chang-ui and the hakchang-ui all worn in accordance to the time and occasion. The po, made for daily wear, would have a straight lape and broad sleeves with a think cord tied at the chest. Various types of po could be distinguished through the presence of a side slit. Although the prevalence of white po would suggest a lack of diversity in terms of color, the combination of a robust and elegant white and the more reserved shade of black used on the gat create a sense of grace and sophistication not seen in any other outfit.

The latter days of King Sunjo’s (r. 1800-1834) sovereignty in the 19th century saw the gat become even larger until the brim would cover a person sitting cross-legged, a diameter of 70-80cm. Headgear policy toward the end of King Heonjong’s rule (r. 1834-1849) was characterized in the Joseon-era encyclopedia, the Ojuyeonmunjangjeonsango, as having changed suddenly to accommodate a larger head capacity with a shorter brim, to around one ja (30.3cm). Following the dress code reform in the 21st and 34th years in King Gojong’s reign (1863-1907), both the crown and the brim were reduced in size.

Amidst the turbulence facing the late Joseon era arising from the opening of the country and the Westernization of its culture, the dress culture of Korea started down the path toward modernization, as traditional clothing became simplified, practical and Westernized. An Enlightenment in Korea grew from the reformist movement of the late 18th century, although the more direct causes were the Korea-Japan Treaty of 1876, succeeded by the Korea-U.S. Treaty of 1882 and the Korea-France Treaty of 1886,

The Westernization of men’s dress initially began with official uniforms, followed by student uniforms and then everyday wear. However, the phenomenon of Westernization was limited to a section of the urban elite, whereas commoners stayed loyal to the traditional hanbok. For Western visitors in Korea a century ago, the sight of the waves of black gat and white robes made for a striking image. The hanbok of this period included the newly-added magoja, a modified version of the Qing Dynasty’s magoe, as well as the baeja, which was an imitation of the Western waistcoat. The latter was more convenient than its traditional predecessor due to the presence of buttons and pockets, therefore becoming widely worn by the public. In addition, wide-sleeved overcoats such as the dopo or chang-ui, which were reserved for the nobility, were abandoned in favor of the narrow-sleeved durumagi, to be worn by all regardless of social class. Thus, equality in the right to dress was established in Korea.

Following this Enlightenment period in the final years of the Joseon Dynasty, when both traditional hanbok and Westernized dress were both worn on the streets in daily life, the wide range of overcoats that men customarily wore throughout the seasons were narrowed down to just the durumagi, while the jokki, a type of vest, and the magoja, a type of outerwear jacket, were newly invented. Instead of the traditional winter jacket of the jangot, a winter overcoat, similar to the durumagi, was also created for women. Hanbok, it seems, adapted to the times.

As seen above, the extensive development in the types of casual hats during the Joseon era was likely related to the social rules that permeated the ancient kingdom at any one time. Such rules always emphasized the dress code. The Chinese geon headgear was closely related to its Joseon counterparts, and was worn by Taoist scholars, literary figures, intellectuals with no desire for public office and by individuals with a well-established livelihood. Indeed, there is no doubt that the black gats actually a low functional and impractical hat. However, the care taken toward the gat, such as the act of using beaded strings to fasten the hat to the wearer’s head, and using galmo, a rain cover for hats made of oiled paper, and a heavy leather case to protect it from the rain, have cemented the dress culture of the period as being representative of the entire culture.

The interest and care that one put into maintaining his gat originated from the social rules of the time. They emphasized etiquette and admiration for the artistic qualities of the gat, its elegant blackness and translucence. Explaining the various changes in gat fashion as being mere trendiness lacks credibility. The diminishing use of the gat with the onset of the 20th century is the result of a change in the livelihood and dress code at the end of the Yi’s family’s over-500-year reign.

The induction of Westernized clothing meant that the gat was no longer worn as an everyday item. However, even today, it is said that family ceremonies, Confucian rituals and traditional events are only complete when the participants dress in dopo, durumagi and gat. Just as hanbok was established as the proper mode of ceremonial dress, the gat remains in use for ceremonial purposes, thus continuing the tradition. The gat was an essential item for any adult throughout the Joseon period and gat-making was a common occupation found everywhere in Korea at the time. Along with the fact that gat-making was the first traditional craftsman technique to be designated as an Important Intangible Cultural Heritage Item, one might hope for a day when the gat is not merely a historical, ornamental headpiece gathering dust atop a wardrobe, but is an essential item to go with one’s hanbok and durumagi on Lunar New Year’s Day.

*This series of article has been made possible through the cooperation of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. (Source: Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea)

The development of the gat over time: Changes in dress codes and hats

In terms of headgear, the representative hat for Joseon-era men was the gat, whose socio-cultural context far surpasses the dictionary definition of the term. The development of the gat has implications not only with regard to the influence of Confucianism during the Joseon period (1392-1910), but also by representing the development of indigenous headwear in Korea. As can be imagined, a diverse range of gat existed during the 500 plus years of the Joseon period. There was the paeraengi, the chorip, the heukrip, the baekrip, the jurip, the okrorip, the jeonrip, the bangnip and the sakkat, for example, all to be worn according to one’s social status and depending on the occasion. In particular, the heukrip was the foremost exemplar of Joseon-era headgear, as it was the representative official hat over the five centuries of the Yi Dynasty’s reign. To date, it remains in use for ceremonial purposes.

The term heukrip can be found in use as early as 1367, the 16th year of King Gongmin’s reign (r. 1351-1374) during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392). The word originated from the production of heukrip decorated with jewelry befitting one’s governmental status. The heukrip prevalent at this time, however, differed from those used later in the Joseon period, and the hat-top decorations on Goryeo-era heukrip allow the speculation that they may have been closer in origin to the balip of the Mongolian Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), established by Kublai Khan. The shape of the heukrip was finalized during the Joseon era, and soon became the hat of choice for the upper class.

Over time, the aesthetic sense of the time shifted, restrictions based on social class were lightened and gat began to be worn by ordinary citizens and by low-level officials. Changes in gat fashion changed, too, alongside such trends. In terms of appearance, the popular hat went through changes in shape, size and brim width, as well as in the materials used in production and in the decorations. Such alterations are evident not only from ancient documents regarding the restrictions placed upon social status, but also from existing paintings and artifacts. According to the Gyeongguk Daejeon, the complete codification of Korean law from Goryeo (918-1392) to Joseon (1392-1910) and published in 1485, officials from the first rank to the third rank were to use silver for the embroidery of their hats, while royal families, including the daegun himself, were permitted to use gold. Hat-top decorations made of jade were permitted for officials in the administrative divisions of the saheonbu, the branch that oversaw the government, the saganwon, the branch that oversaw the monarchy, and the jeoldosa, the military chiefs. Finally, government inspectors wore crystals on top of their hats. This would suggest that the late Goryeo-era policy of wearing decorated heukrip was in place at least by the time of King Seongjong (r. 1469-1494), during the early Joseon era.

Although the precise form of early Joseon gat is indeterminable, records exist regarding the gat, the heukrip, the gojeonglip, the jungnip and the chorip. The shape of the gat was first discussed during the reign of King Seongjeong (r. 1469-1494), when it was name the ibche wonjeong-I cheomgwang, meaning that it had “a round top and a broad brim.” It was decreed that all gat would be produced following this format.

It would appear that following King Seongjong, the gat neared its stage of completion. From the hemispherical crown and broad brim of the balip, the gat was altered to have a more cylindrical crown with a narrow top and a broader base, and was produced using a more diverse range of materials. Having undergone phases such as the pyeongnyangja and chorip, headgear in Korea culminated in the heukrip, which is representative of the Joseon period.

The heukrip is made by attaching the yangtae, or brim, to the daewu, or crown, wherein the former is somewhat curved at the rim, while the latter is cylindrical and broader at the base with a flat peak. The crown and brim are meshed using fine bamboo threads cut to a hair’s breadth, and the heurip is completed with a black lacquer finish. The hat was considered a part of comfortable dress, mainly worn by the gentry in their daily lives. It was an indigenous invention of the Joseon people, with sartorial influences from neighboring kingdoms, and saw widespread use until the latter days of the Yi family’s reign. Despite the popularity of the black style, different occasions required the use of different colors; for example, the red-lacquered jurip was worn as part of the uniform for a military dangsanggwan, or senior official, while the white baekrip was worn on occasions of national mourning.

While in some cases, only bamboo threads were used for the hat crown and brim, some used horsehair for the crown. Further distinctions can be made through the cover enveloping the crown and brim. Dependinon the material and method of production, the heukrip can be subdivided into categories such as the jinsarip, the eumyangsarip, the eumyangrip, the mamirip and the porip.

(Left) Peacock feathers and amber strings; (right) Jade accessories adorn the crown of a hat

Amber gat straps are reserved exclusively for the dangsanggwan, but the recent trend of excess is worsening day by day, to the extent that bureaucrats, hereditary officials and military officers, as well as dangsanggwan and chamha (the lowest-level officials) are insisting on using amber. (from the Gyeongguk Daejeon, 1485)

The custom of using both beads and silk for the gat strap began during the vacation in Onyang. For the most part, it was out of concern that the gat strap would snap, but it persisted to become a customary practice. (from the Gyeongguk Daejeon, 1485)

From the chronology of changes made to the gat, it is evident that the headgear was initially round at the crown with a broad rim and that the crown became gradually higher and the rim remained broad. During the reign of King Myeongjong (r. 1545-1567), the crown was excessively low, to the point of resembling a small plate atop a larger plate, while the brim resembled a small umbrella. This trend was mocked for its similarity to the hat worn by monks, the seungnip. The variation created to compensate for this shape was, in turn, ridiculed for its disproportionately high crown and narrow brim. Alterations such as these show the effect of fashion trends of the period on the development of headgear.

Indeed, the gat of the early 16th century, toward the end of the Yeonsangun’s reign (r. 1494-1506), showed many changes regarding the height of the crown and the width of the brim. Headgear policy during the reign of King Jungjong (r. 1506-1544) was variable to the point of frivolity. The gat of this period began with a tall crown and a wide brim, but toward the end of this period, when the hat had become even higher while the brim became narrower. King Myeongjong’s reign saw the crown lowered and the brim broadened again.

Subsequently, complaints were made during King Hyojong’s time on the throne (r. 1649-1659) that the gat brim was too wide, to the point of being caught on doorframes. In contrast, King Sukjong (r. 1674-1720) saw that both the crown and the brim were reduced to an extent that caused controversy, as it was said to be in violation of past policy.

Critic Yi Deok-mu wrote that, “The hat-brims of olden days could barely cover the shoulders, but now, they are too broad and take up more space than a person covers when sitting cross-legged. At present, the design of the gat is deplorable and strange, being neither aesthetically pleasing nor easy to use. The excessive size errs on the side of extravagance and wastefulness, and there is a dire need to instigate regulations and discontinue this already-familiar custom in order to resist further negative repercussions.”

Yi Deok-mu blamed the arrogant conduct of the nobility entirely upon the gat. He felt the translucent headgear could neither provide shelter form the rain nor from the sunlight and yet the reverence that men had for their gat was exceptional. The gat was an ornate affair, not only with regard to the body of the hat but also to the chin strap (gakkeun). According to the Gyeongguk Daejeon, a code of law promulgated in 1485 that dictated one’s behavior, clothes and other local ordinances, only officials above the level of dangsanggwan were permitted to use gold and jape on their chin strap, while the lower-leveled danghagwan were prohibited from using agate, amber, coral or lapis lazuli. The social disorder and instability of the legal system at the time led to the emergence of the class-based regulation when one’s gat strap became a social issue.

Furthermore, the gat straps used by the nobility were comprised of beads made from ivory, agate and bamboo, of such a length that some drooped down below the waist. Some examples have been found of a lengthy gat strap curled around the ears. Changes were also seen in gat straps, such as the use of silk thread. During one of King Yeongjo’s (r. 1724-1776) sojourns at a hot springs in Gwacheon-hyeon, silk thread was first used along with previous stones for the gat strap.

The competition over the size of the gat and the lavishness of the strap was not only the culmination of the nobility’s desire to display their wealth, but also the somewhat more subtle show of the availability of leisure time necessary for dressing properly. Such pursuits became the measure upon which the nobility compared each other’s fashion and elegant taste.

Through King Seonjo’s reign (r. 1567-1608), the height of the crown was raised to around eight chi (24.314cm, 1 chi= 3.03cm), with a narrower brim. This trend was reversed in the Gwanghaegun’s reign (r. 1608-1623). Records from King Injo’s reign (r. 1623-1649) indicate that, “following the years of gyemi [1643] and gapsin [1644], the gat crown was suddenly made taller and larger, with the brim following suit, to become much broader.” Minutes from discussions regarding official dress policy during Hyojong’s reign (r. 1649-1659) document the complaint that the crown and the brim of the gat have become too tall and wide, and have become a hindrance when entering doorways. At this time, the height of the crown was set at four chi and five pun (13.5cm) using a pobaekcheok, a special ruler used for measuring items of clothing.

Around the time of King Yeongjo’s reign (r. 1724-1776) in the 18th century, the crown’s height was raised and the brim broadened once again. As apparent from the cultural remains from the period, the gat of Yeongjo and Jeongjo’s reigns (1724-1776 and 1776-1800) had relatively wide brims, while the straps made of materials such as cloudy amber, amber and turtle shell, added to the glamour.

A high-ranking military official’s felt hat adorned with peacock feathers.

In the late Joseon period, the range of robes became more diverse, with variants such as the dopo, the jungchimak, the chang-ui and the hakchang-ui all worn in accordance to the time and occasion. The po, made for daily wear, would have a straight lape and broad sleeves with a think cord tied at the chest. Various types of po could be distinguished through the presence of a side slit. Although the prevalence of white po would suggest a lack of diversity in terms of color, the combination of a robust and elegant white and the more reserved shade of black used on the gat create a sense of grace and sophistication not seen in any other outfit.

Cheonggeumsangryeon, “Resounding geomungo and praiseworthy lotus,” 1758, by Shin Yun-bok.

The latter days of King Sunjo’s (r. 1800-1834) sovereignty in the 19th century saw the gat become even larger until the brim would cover a person sitting cross-legged, a diameter of 70-80cm. Headgear policy toward the end of King Heonjong’s rule (r. 1834-1849) was characterized in the Joseon-era encyclopedia, the Ojuyeonmunjangjeonsango, as having changed suddenly to accommodate a larger head capacity with a shorter brim, to around one ja (30.3cm). Following the dress code reform in the 21st and 34th years in King Gojong’s reign (1863-1907), both the crown and the brim were reduced in size.

Amidst the turbulence facing the late Joseon era arising from the opening of the country and the Westernization of its culture, the dress culture of Korea started down the path toward modernization, as traditional clothing became simplified, practical and Westernized. An Enlightenment in Korea grew from the reformist movement of the late 18th century, although the more direct causes were the Korea-Japan Treaty of 1876, succeeded by the Korea-U.S. Treaty of 1882 and the Korea-France Treaty of 1886,

The Westernization of men’s dress initially began with official uniforms, followed by student uniforms and then everyday wear. However, the phenomenon of Westernization was limited to a section of the urban elite, whereas commoners stayed loyal to the traditional hanbok. For Western visitors in Korea a century ago, the sight of the waves of black gat and white robes made for a striking image. The hanbok of this period included the newly-added magoja, a modified version of the Qing Dynasty’s magoe, as well as the baeja, which was an imitation of the Western waistcoat. The latter was more convenient than its traditional predecessor due to the presence of buttons and pockets, therefore becoming widely worn by the public. In addition, wide-sleeved overcoats such as the dopo or chang-ui, which were reserved for the nobility, were abandoned in favor of the narrow-sleeved durumagi, to be worn by all regardless of social class. Thus, equality in the right to dress was established in Korea.

Following this Enlightenment period in the final years of the Joseon Dynasty, when both traditional hanbok and Westernized dress were both worn on the streets in daily life, the wide range of overcoats that men customarily wore throughout the seasons were narrowed down to just the durumagi, while the jokki, a type of vest, and the magoja, a type of outerwear jacket, were newly invented. Instead of the traditional winter jacket of the jangot, a winter overcoat, similar to the durumagi, was also created for women. Hanbok, it seems, adapted to the times.

As seen above, the extensive development in the types of casual hats during the Joseon era was likely related to the social rules that permeated the ancient kingdom at any one time. Such rules always emphasized the dress code. The Chinese geon headgear was closely related to its Joseon counterparts, and was worn by Taoist scholars, literary figures, intellectuals with no desire for public office and by individuals with a well-established livelihood. Indeed, there is no doubt that the black gats actually a low functional and impractical hat. However, the care taken toward the gat, such as the act of using beaded strings to fasten the hat to the wearer’s head, and using galmo, a rain cover for hats made of oiled paper, and a heavy leather case to protect it from the rain, have cemented the dress culture of the period as being representative of the entire culture.

(Left) Hats of a family on a picnic; (right) A Korean wearing his gat and hanbok and a Westerner wearing his felt hat and boots.

The interest and care that one put into maintaining his gat originated from the social rules of the time. They emphasized etiquette and admiration for the artistic qualities of the gat, its elegant blackness and translucence. Explaining the various changes in gat fashion as being mere trendiness lacks credibility. The diminishing use of the gat with the onset of the 20th century is the result of a change in the livelihood and dress code at the end of the Yi’s family’s over-500-year reign.

The induction of Westernized clothing meant that the gat was no longer worn as an everyday item. However, even today, it is said that family ceremonies, Confucian rituals and traditional events are only complete when the participants dress in dopo, durumagi and gat. Just as hanbok was established as the proper mode of ceremonial dress, the gat remains in use for ceremonial purposes, thus continuing the tradition. The gat was an essential item for any adult throughout the Joseon period and gat-making was a common occupation found everywhere in Korea at the time. Along with the fact that gat-making was the first traditional craftsman technique to be designated as an Important Intangible Cultural Heritage Item, one might hope for a day when the gat is not merely a historical, ornamental headpiece gathering dust atop a wardrobe, but is an essential item to go with one’s hanbok and durumagi on Lunar New Year’s Day.

A gat and other headgear worn by a group of men

*This series of article has been made possible through the cooperation of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. (Source: Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea)