- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

Shortly after the term “punk” was coined to represent this chaotic new musical movement in the late ‘70s, people started asking, “Is punk dead?” And the question has been asked ever since, in music scenes around the world.

Punk in Korea has had two previous golden ages, where there were prominent bands making music for a distinct community. The second grew from the ashes of the first. After the scene built around Drug Records and Joseon punk of the ‘90s got too big and unresponsive, the younger bands came together in new groups, the most prominent being Skunk Label. Run by Won Jonghee, lead vocalist of the streetpunk band Rux, they opened a venue in a tiny basement on the wrong side of the tracks near Sinchon. Later, in January 2005, Skunk reopened in a new location—the former venue of Drug Records, which continued to serve as ground zero for punk in Korea.

On Tuesday, January 20, I came from Suwon to Seoul to meet with Jonghee, to find him standing in the former Drug covering up the old spraypaint on the walls with new stuff. All that history, I thought.

Jonghee handed me a spray can. “It’s time to start our own history.”

Jonghee covers the walls of the new Skunk Hell with spraypaint in -20 weather.

Skunk Hell opened on Saturday, January 24, with 14 bands playing all night until the first subway of the morning. Naturally, I drank way too much, broke my camera, and lost my glasses.

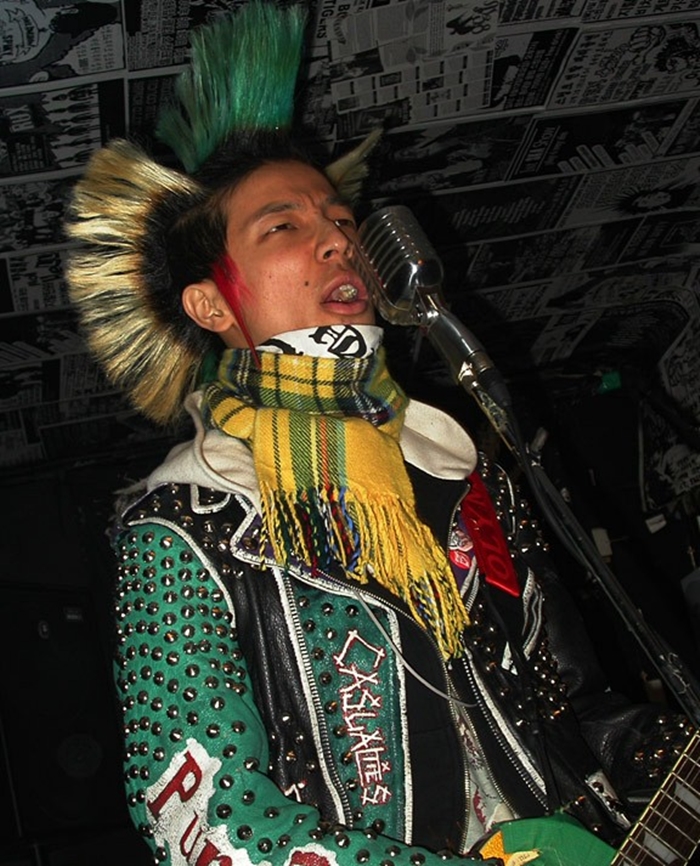

Rux plays at Skunk Hell's first show.

The main bands back then were Rux, Couch, and Spiky Brats. Following the Joseon punk bands, which were a blender of influences trying to find footing in Korea, the Skunk bands took near-complete concepts and ran with them. Rux was a streetpunk band occupying a common ground between American punk band Rancid and UK oi band Cock Sparrer.

Rux in Skunk Hell in 2008

Many of their songs were bilingual, alternating between Korean and English. In “우리는 한마음” the chorus is “We should all unite because our minds are all the same.”

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DJtqzdsb0oY

Most of the bands were iconic punk, clad in studded leather, patches, and big boots, and frequently had their hair up in multicoloured liberty spikes and mohawks. In those days in Korea, that made you look dangerous, not like a cosplayer or fan of Big Bang.

I seem to recall the hairdresser DonaldK was using Korean punks as his test subjects, creating this trihawk on Spiky Brats member Byungsun.

Skunk Hell—and Drug—has always been a dingy basement, decorated with spraypaint and gig posters rather than normal materials. There was a welded metal shelf separating the stage from the crowd, which made it easy to stage dive and kept the bands safe. The more senior members of the scene would come up on stage and stand or sit along either side, to show their support for the band and sing along.

When New York ska band the Slackers played in Skunk in 2007, the barrier wasn't much help when saxist Dave Hillyard was grabbed by fans.

It was important having a venue owned and operated by punks. All the other clubs at the time were owned by older guys who hated punk music, and they would charge high rental fees to promoters. At Skunk, we could do what we wanted.

The biggest shows must have had around 200 paying customers, but sometimes it was lower than 20.

Shows back then started early and ended early, mainly so the younger people could get the last train home. But most of us would stay out all night waiting for the first train. After about half an hour of waiting around after a show and cleaning, someone would lead everyone to the afterparty.

Usually cleaning took a bit of time.

After a show ended, we would go and fill a restaurant with punks and keep it open until early in the morning, or hang out in Hongdae Playground.

The only non-punks in this restaurant worked there.

Back in those days, it was still pretty rare to see foreigners at concerts in Hongdae, or even in the playground. The area wasn’t quite the flashy party district it is today, and foreigners didn’t have any way of finding shows. The few foreigners who did make it didn’t last long, and more than once I heard someone say “I wish I found out about Skunk sooner! This is my last month here.”

The foreigners that did stick around longer became pretty well known.

The Korean punks were hungry for information and contact with the outside world. One American soldier who became a regular helped them order stuff online, and before he knew it, everyone was flooding him with orders of stuff they wanted to get from overseas.

Putting on new patches.

The Korean punk scene always had a close relationship with Japan’s punk scene, which unlike ours stretches back pretty close to the beginning of ‘70s punk. I recall even one time, a Japanese band played in Skunk Hell on March 1, only figuring out it was a major national holiday marking resistance to Japanese occupation. They were unnerved during their set but the Koreans there were all thoroughly appreciative.

On June 26, 2004, we had the first Korea/Japan Oi! Festival, bringing seven Japanese bands to Seoul to perform alongside nine local bands, all for just KRW 20,000. The show was intense and exciting, giving us a glimpse of one corner of the Japanese punk scene and letting the Korean punks stand up and represent their scene. And they gave it their best, showing their visiting Japanese friends the best of the local scene.

This festival has been held nearly every year ever since, the most recent one in Korea being held on 16 November 2013.

Korean and Japanese punks and skinheads pose for a group photo outside Skunk Hell.

Summer 2004 was brutally hot, and the higher the temperature climbed, the more people we had coming to Skunk Hell, making it increasingly sweaty and unpleasant inside. At its peak, the whole room was packed with people to be lightly pressurised, and the walls dripped with condensation as if they were actually sweating.

I'm 70 percent sure this is 49 Morphines. EDIT: Turns out it's Vassline.

Skunk was starting to wear out its welcome in the neighbourhood, with legal actions threatened and neighbours lodging formal complaints about the noise and the weirdos coming out to shows. Our shows were loud, although no louder than many other parts of the neighbourhood where nightclubs played hip-hop and pop and had more fights and other troubles.

A Korean comic book set in Hongdae has one frame in front of Skunk Hell.

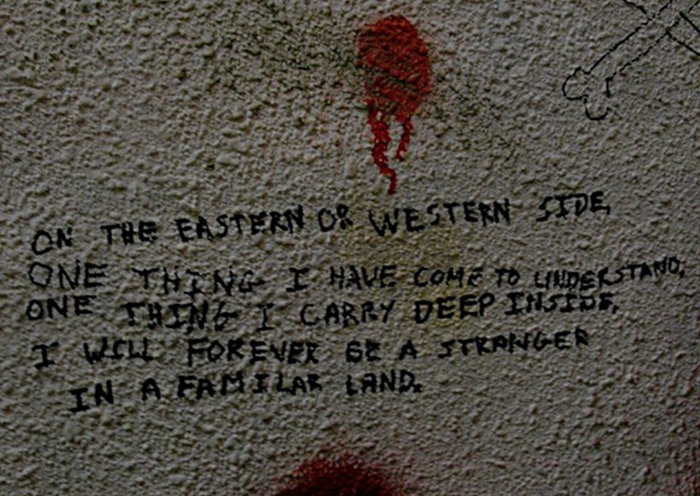

In fall, we were visited by Paul, a half-Korean American army brat who used to play guitar in Rux before moving to the US for university. Before my time, he ran away from home and spent some time living in the first Skunk Hell by the train tracks. During his brief visit, he wrote a poem on the wall right outside Skunk Hell’s front door.

On the eastern or western side/ One thing I have come to understand/ One thing I carry deep inside/ I will always be a stranger/ In a familiar land.

Paul moved back to Korea a few months later in early 2005 after not taking his studies seriously and making too many enemies stateside. The first time he went to a show, he started moshing and within seconds punched me, hard, in the ribs. Ouch, but he turned a show with mediocre attendance into a riot. Paul was full of energy and ideas. He wanted to start a punk zine, and we quickly founded Broke in Korea, which is about to celebrate its 10th anniversary this weekend.

Here's me with Paul and a couple other Korean punks.

Suck Stuff, a punk band in love with the Clash, was led by Chulhwan, the founder of BPJC. Paul was invited to join the band, placing two of the scene’s best songwriters in the same band. They gradually became one of the main bands of Skunk Hell, and Chulhwan gradually replaced Jonghee as the main organiser of shows.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e5UFKXmmBoU

Various other bands rose and fell under the Skunk Dynasty. Big-name bands like Kingston Rudieska and Galaxy Express had their debut shows here. Shorty Cat, originally formed by the girlfriends of punk musicians, was perhaps Korea’s third all-girl punk band, and their cutesy-aggressive version of punk appealed to young girls and lecherous older guys.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=whI1qcLuLG0

Once at a show, the door girl left her post and someone took all the door money. Paul passed a hat around to the foreigners at the show, and we raised more money than had been stolen. In appreciation, a special show was put on with a discount for foreigners headlined by Suck Stuff and 13 Steps.

The big event of 2005 was a visit from Champion, a Seattle-based straight-edge band that had previously met Geeks frontman Kiseok in the US. They were touring Japan and it wasn’t a lot of money to lure them over to Korea at the end for three more shows: Anyang, Seoul, and Cheongju. I went to all three. The Korean bands were in top form, and Champion were treated like royalty. Their visit led to many future foreign hardcore tours to Korea. I asked the members of Champion how touring Korea stacked up to Japan. The crowds were smaller here, obviously, but the kids were so much more excited to see a touring band. There was never a time when someone wasn’t with them here, and they made plenty of friends. Rather than hotels, they stayed in people’s homes. In Japan they did a serious tour, going from city to city and playing shows every night. It was a professional deal and there was no time to sightsee and no time to make friends; the Japanese touring machine is too efficient for that. Korea was the first break they had.

Champion perform in Skunk Hell on March 2, 2005.

Skunk Hell continued facing increasing competition for the next few years, as the number of venues increased but the audiences failed to keep up. Some weeks, there would be only ten paying customers at Skunk shows, and with no liquor revenue, that was a cyanide pill. They stayed open several more months relying on loans and donations from friends and supporters, but the fate of Skunk Hell was inevitable.

"I think it should have been closed earlier," said Chulhwan.

"I feel free," said Jonghee. "There’s more bands, but there’s much more clubs right now, so the clubs have no bands. Some clubs have to close down and some clubs have to do other music. Skunk won’t compete with other clubs ‘cause we just wanted the punk bands to be free to play."

Rux on 1 March 2008

After months of inactivity, Skunk had its farewell show on 3 January 2009. Probably not the best decision, but they had Galaxy Express, Rux, Crying Nut, and a few other bands play, for free. The place was packed tighter than ever before, and the last show was a huge blowout, but it was mostly appreciated by Crying Nut fans, while the main Skunk supporters were stuck outside unwilling to brave the screaming fans.

Jonghee of Rux and Han Gyeong-rok of Crying Nut joined arms to close Skunk Hell together.

Rux and Suck Stuff both signed to Dope Entertainment and continue to make music. Paul left Suck Stuff and joined the US Army. Many other Skunk regulars grew up, started successful businesses, embarked on real careers, or became famous as musicians.

The punk scene never found another home base quite like Skunk Hell. Today, punk in Korea has moved away from the Skunk era, with more bands playing harder and angrier music and much less emphasis on appearance.

I look back fondly on the Skunk era as a time when Korean youths (well, mainly those in their 20s) were discovering and playing around with new musical concepts and having a lot of fun doing it. The punk community was small and everyone knew each other, and we didn't always know what we were doing but we were among the first to give it a try in Korea.

Group photo

By Jon Dunbar for the Korea Blog