View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

Born in Gyeongju, North Gyeongsang Province in 1915, Pak Mogwol first became well known for writing children’s poetry. In 1933, his poem “Tong-ttak-ttak Tong-ttak-ttak” was selected for a prize by the magazine Child, and in the same year another poem, “Welcoming the Swallows,” was awarded a prize by New Family magazine. Then in 1939 his work was recommended by Jeong Ji-yong and published in the September edition of Sentence, thus launching his career as a poet in earnest. From then onwards, Pak Mogwol made a place for himself in the history of modern Korean poetry as the consummate creator of concise, simply constructed lyric poetry.

As a nature poet, drawing on and embodying the sensual realities humming in nature and metaphysical meaning, he is best remembered as part of the Cheongnokpa (Green Deer Group) which was born out of the three-poet anthology published in 1946 and entitled Cheongnokjip (Green Deer Collection), which was also Pak’s first published collection of poetry. In this work there is a strong undercurrent of a specific form of purely lyrical methodology running throughout.

The subject matter of Pak Mogwol’s early poetry is nature. However, rather than being a physical kind of nature where the principle of survival of the fittest rules, or an agricultural, bucolic kind of nature, it is nature transformed, so to speak, in the imagination of the poet, reflecting his attitude and outlook on life. An examination of poems such as “Blue Deer” or “April” which are typical of his early works, shows that such a hypothesis is highly convincing. The settings of these poems such as “Cheongun Temple on a faraway Mountain,” “Jahasan,” and “a remote peak/the wind laced with pine pollen” are not so much realistic descriptions of locations in Korea. Rather, they are nature imagined, projected with archetypal ideals to accompany characters such as a “blue deer” and a “blind young woman,” who are the real focus of the poems.

This perfectly intact, imagined world of nature is continually transformed and reproduced in lines such as: “Every wine-mellowing village/ afire in the evening light,” from “The Wayfarer,” and “The mountain/ Gugangsan/ a rocky violet-tinged mountain,” from “Wild Peach Blossoms 1.” This nature, then, becomes something which, shaking off the dust of the everyday world, people can seek without constraint, and be held within its warm embrace. In this way, the nature that appears throughout Mogwol’s early poetry is not inherently the real nature of the agricultural world, but an image of ‘Eden’ conceived of by the poet’s own longing for the divine, the source of all things. Therefore, when the blind young woman in “April,” “puts her ear to the lattice door/ and listens,” it alludes both to the sound of nature and at the same time to the “sound of silence” as an imagined model of divinity.

Towards the middle of his career, Mogwol turned his focus to the sphere of everyday life and, in particular, the communal unit that is the “family.” At the same time, through the substantiality of life and death, his poems sang of earthly love. Consider “Lowering of the Coffin,” which, through the narrator’s eulogizing his own flesh-and-blood younger sibling, allows the soul of the deceased to depart—a masterpiece that expresses devoted love and compassion. The dark heavy image of descent in lines such as: “The coffin was lowered by ropes/ as if into the deep well of the heart,” “world where snow and rain comes down,” and “when fruits fall” acts both to evoke the death of the younger sibling as it happened and to allow us to feel the depth of the narrator’s inner sorrow. In particular, the onomatopoeia of “jwa-reu-reu” and “tuk” appear as vehicular language making the distance between life and death tangible. Here the ropes serve the purpose of lowering the coffin, but they also act as a sort of link between the impassable boundary that divides life and death, and thus the ropes become a means of transmitting the love felt by the living. Therefore, the ropes lower into “the deep well of the heart.”

Another masterpiece, “Family,” expresses the exhaustion of life and a boundless sense of pity for one’s family and oneself. In a home on this Earth live “nine pairs of shoes, different sizes.” Here the walls built of “snow and ice” by the head of a household, who has walked back home along a path of snow and ice, are tangible. However, the reaction to this life of pity appears as “the smile on my face.” Even though it is a life of “treading a way of humiliation and hunger and cold”—this is melted away by the warmth of ardent love.

In “Song of Farewell,” on the other hand, Mogwol reacts to the physical event of death, bringing in the impossibility of communication between the space that separates “you” on the far banks of the river and “me” at the prow of a boat. The “river” separates the two, with one in this world and one in the next world. The narrator on this side of the river can hear a voice coming from the other side, but with the wind blowing it is impossible to make out the meaning of what is being said, and “my” voice asking of the meaning is blown asunder by the gale. A rope that is eroding and weakening is the tie which once bound “you” and “I” in this life. Even if the connection between the two in this life is over, their ties in the next world are something that cannot be known and so we hear the following lines: “Let’s not depart, let’s not depart/ the tie is the wind that crosses the reed bed.” “Let’s not depart” is both “your” words that “I” cannot hear, and a parting greeting from deep down in the narrator’s heart. This is why the narrator responds, “Alright. Alright. Alright./ If not in this world at least in the next...” In the end, through the event of death, this poem actually serves to create affirmation and a philosophical view of life, while also displaying the adaptive quality of the poet’s imagination.

In Mogwol’s later poetry, while still addressing the concreteness of everyday life, he also leans towards ontology and a broader outlook upon life. In his later work, traces of the discipline of his early poems, characterized by linguistic craftsmanship and implication, become difficult to detect, and through an increasingly prose-like form of poetry, Mogwol’s spiritual position is clearly marked out. For example, in “Empty Glass” the poet shows us a self that longs for the emptiness that in fact represents a state of being full to the brim. The “empty glass,” therefore, represents a pure and ordered life. However, the narrator says, “But there cannot be in this world/ things that are empty and void.” This is because “you” do not leave it to be empty. No matter what, “If not filled/ with cool resignation/ it is filled with the water of faith.” Here “cool resignation” represents a self-awareness of human limitations, and it is only then that resigned affirmation of the providence of a higher being can begin. If it is not with coolness, then the empty glass is filled with something soft and warm like the absolute “water of faith.” In this way, God’s providence is not something the narrator has any say in, but is rather a form of grace that he must accommodate unconditionally. Of course such self-awareness is not based on rational principle but on religious experience.

In “Epiphany” for instance, the poet alludes to the experience of a miracle which took place beside the Pool of Siloam as recounted in the New Testament, where eyes that see things “just as they are” refers to the importance of being able to sense the ethereal. This is both a form of self-discipline for a worldly being enraptured by empty desire and a record of introspection regarding the futility of myopic ardor. In the end, in the poetry of his later years, Mogwol shows the stance of accepting a “you” which is completely other, singing of unlimited affirmation for the “absolute being” which pre-exists one’s own life and consciousness.

Continuing the Legacy of Mogwol’s Lyric Poetry

Pak Mogwol was an active poet for forty years, from his debut in 1939 until his death in 1978, and during this time he was a great mentor who guided many poets along their intended path. These poets came together and founded an organization called the Mogwol Literature Forum. The Forum has organized various events to commemorate the centennial anniversary of Pak’s birth, and published a poetry collection, Lonesome Hunger, in memoriam. A total of forty poets contributed to Lonesome Hunger, and surveying the members of the group, we can see that they are the major representative poets in Korean poetry circles.

Actually, Pak’s students, the poets belonging to the Mogwol Literature Forum, can be classified into different groups. First of all, there are the poets from the 1960s who debuted in prominent literary journals through Pak’s recommendations. Second are the poets who debuted in Pak’s professional journal, Simsang, which began publication in 1973. Finally, there are the poets who studied with him during his career as a professor at Hanyang University and then made their debut, even if this did not involve Pak’s recommendation.

Only by understanding the uniquely Korean recommendations process, the way in which writers are inaugurated into the writing community, can one truly understand that later generations of poets write to carry on his legacy. Passing through the recommendations system is the special way that poets and novelists join the literary community and launch their writing careers. In fact, the Korean words for “literary community” (mundan) and “joining the community in one’s literary debut” (deungdan) are characteristically Korean in that they imply a degree of exclusivity. This exclusivity means that one cannot become a poet or novelist without first being recognized by an already established poet or novelist.

This distinctive method by which authors debut is either through the recommendations system (chucheonjae) in the case of literary journals, or the annual spring literary contests (sinchunmunye) in the popular dailies. The two systems have different names and differ slightly in their methods, but they are ultimately alike in that through them an established writer recognizes the work of a new writer. For this reason, writers usually assume “junior” or “senior” status in the Korean writing community according to the year in which they debut rather than with reference to age. By extension, terms such as “poets of the 60s” and “poets of the 70s” also classify poets largely according to the year they debuted. As the debut system was at one time relatively strict, writers had to be recommended three times before they had completed the process. Also, new writers were permanently stamped with the mark of the writer who recommended them in a particular journal, and this recommendation also became a yardstick for evaluating their ability. Therefore, if writers received Pak’s recommendation, it meant that they were esteemed as being the most talented at the time.

The recommendations system came into being in 1939 in Munjang, a journal that was forcibly shut down by the Japanese colonial government in 1941. Pak was among the poets who debuted in Munjang, in 1939. At that time, he received a recommendation from the poet Chong Chi-yong and was published in the journal. It is a well-known story that Chong gave Pak the highest praise, mentioning him together with Kim Sowol in his recommendation letter: “Just as the North had Sowol, it is natural that the South would have Mogwol.” Although many poets debuted in Munjang, the ones remembered together with Pak Mogwol are Pak Tu-jin and Cho Chi-hun. This is because the three of them are known in literary history as members of the Green Deer Group (Cheongnokpa), named after their book of poetry and illustrations entitled Green Deer Collection (Cheongnokjip) published in 1946, the year after Korea was liberated from Japan. In fact, we could say that the journal Munjang was the agent of fate bringing the group together.

The first group of poets that has extended Pak’s legacy debuted in literary journals or in the spring writing contests in the 1960s or 1970s, owing to Pak’s recommendation. Lee Jung was the first poet so honored. After that came Heo Young Ja, Kim Jong-hae, Lee Seung-hoon, Kim Young-jun, Yu An-Jin, Park Geon-han, Jeong Min-ho, Kim Jun-sik, Lee Geon-cheong, Oh Sae-young, Yu Seong-u, Cho Jeonggwon, Na Tae-joo, Lee Chae-gang, Shin Dalja, Lee Geun-shik, Kim Myong-bae, Seo Young-su, Shin Gyu-ho, Jeong Ho-seung, Yu Jae-young, and Yun Seok-san. These poets debuted in magazines such as Hyundae Munhak until the early 1970s. A number of the poets mentioned above also studied with Pak at Hanyang University: Lee Seung-hoon, Park Geon-han, Lee Geon-cheong, Yu Seong-u (graduate school), and Yun Seok-san (Yun was not directly recommended by Pak, but can be counted as a student from Pak’s early period).

The second group debuted in Simsang, the journal Pak published beginning in 1973. The poets included in this group are: Kim Seong-chun, Han Gwang-gu, Lee Jun-gwan, Kwon Taek-myeong, Kim Yong-beom, Han Gi-pal, Kwon Dal-ung, Lee Myeong-su, Jo U-seong, Mok Cheol-su, Yun Gang-no, Lee Eon-bin, Lee Sang-guk, Hwang Geun-sik, and Shin Hyeop. These were the major poets at the forefront of the poetry scene in the 1970s. Some of them also studied with Pak at Hanyang University: Kim Yong-beom, Kwan Dal-ung, Jo U-seong, and Mok Cheol-su.

Pak Mogwol died in 1978, so it was impossible for anyone to receive his recommendation after that. The third group of poets—Park Sang Chun and Lee Sang-ho—were not directly recommended by Pak, but studied Korean Language and Literature with him at Hanyang University and debuted in the early 1980s. This was the last generation to study poetry with him in his days as a university professor. Pak’s students and heirs that debuted in the 1970s and 1980s, including the ones mentioned earlier in this paragraph, once formed a group called Simgakgak, and garnered much attention for being leading young poets. Not only that, but the Mogwol Literature Forum poets are all important members of the Society of Korean Poets, and Forum poets Heo Young-ja, Kim Jong-hae, Lee Geon-cheong, Oh Sae-young, and Shin Dalja have also served as president. It is because their teacher, Pak Mogwol, was deeply connected to the organization that his successors could function as important members and become president themselves. Thus we can say that the poets Pak mentored were following their teacher’s example by participating in the society and assuming leadership roles as poets.

Through membership in the Forum, Pak’s students and heirs can take pride in their teacher and be actively involved in the literary community. The members of the Forum all write poetry in their own individual style, but they are alike in that they are Pak’s students, following after their teacher by extending the literary legacy of Korean lyric poetry.

Hearts Pay Tribute to “Big, Soft Hands”

This year marks the 100th Anniversary of the birth of the poet Pak Mogwol. Pak Mogwol, whose given name was Yeong Jong-in, was born on January 6th, 1915. By way of a recommendation from Chong Chi-yong, he debuted in 1939 in the literary magazine Munjang. After his debut, Mogwol published in Cheongnokjib along with the poets Cho Chi-hun and Pak Tu-jin; together they became widely known as the “Cheongnokpa” (Green Deer Group) and were influential in guiding the path of Korean lyric poetry. There is no hesitation in calling Pak Mogwol our “National Poet” because so many of his outstanding lyric poems, such as “The Wayfarer,” “The Mountain Peach,” “April,” and “Song of April,” are held in the hearts of the nation. His students and those who cherish his memory have come together over the past year to celebrate the centennial of his birth with academic conferences, exhibitions, musical performances, and a variety of other events, as well as the publication of a memorial book, CD, and more. These diverse events and commemorative projects happening all over the country were only possible due to the many people who have been missing their “National Poet.”

The various events for the 100th Anniversary of the poet’s birth have been accomplished through the combined efforts of four organizations: the Mogwol Literary Forum, Hanyang University, the Tong-ni·Mogwol Memorial Society, and the poetry journal Simsang.

The first event was a dinner jointly hosted by the Mogwol Literary Forum, Hanyang University, the Tong-ni·Mogwol Memorial Society, and Simsang Publishers. The dinner was held on the anniversary of Mogwol’s death, March 24th, at Literature House Seoul, where around 150 guests, including veteran poets like Kim Jong-Gil, and Mogwol’s former students were in attendance for the event, which covered all aspects of the literary world.

It was at this dinner that the head of the Mogwol Literary Forum, Lee Geon Cheong, made the following summation of Mogwol’s poetry: “In spite of living through the situation where the Japanese Colonial Government had attempted to erase the Korean language, Mogwol’s poetry faithfully expresses elements in Korean lyric poetry that have the feel of our language and an inherently Korean sentiment.” Many poets, such as Lee Keun-bae and Yoo An-Jin also reminisced about Mogwol’s tender side, conveying that he was more than just a literature teacher, he was a teacher of life. Poets including Shin Dalja, Kim Jong-hae, Lee Sang-ho, and Na Tae-joo recited a selection of his poems.

Matching up perfectly with the timing of the memorial dinner, the Mogwol Literary Forum, which is composed of Mogwol’s former students, published a collection of poems dedicated to their teacher titled Lonesome Hunger. This collection includes elegies from forty poets who were either able to debut due to Mogwol’s recommendation or who studied under him at Hanyang University.

Hanyang University is the school that nurtured Mogwol’s students since he was appointed a professor there in 1962. The Hanyang University Museum held a special exhibition in honor of the centennial of his birth. This exhibit, which opened on April 24th and will run through the end of the year, has attracted much attention, not only for being a showcase of Mogwol’s poetic success, but also because it includes letters he sent to his students as well as other personal effects that show his human side. In addition, an academic seminar titled “The ‘Nowness’ and Re-recognition of Pak Mogwol’s Literature” took place on April 25th. This seminar provided an opportunity for six professors, including Yoo Jong-ho, Lee Namho, and Lee Jae-bok, to present papers that shed a new light on Mogwol’s literary works.

Hanyang University also published a number of anniversary books and CDs for the occasion. One was a book titled Paiknam’s Music, Mogwol’s Poetry. “Paiknam” Kim Yeon-jun, in addition to being a composer and one of the founders of Hanyang University, composed several songs during Mogwol’s tenure at Hanyang that were based on his poetry. This book, which shines a light on the two artists’ collaboration, has even more significance for the fact that last year marked 100 years since “Paiknam” Kim Yeon-jun’s birth. A CD containing fourteen traditional Korean-style compositions by Paiknam with lyrics by Mogwol was released to commemorate the book’s publication. In addition to this, a collection of Mogwol’s essays titled The Moon and Rubber Shoes was published to highlight his essay writing skills, and was accompanied by a pictorial CD showing various activities from his years at Hanyang.

The Tong-ni·Mogwol Memorial Society is the organization that, in December 2002, founded the Tong-ni·Mogwol Literary Center in the city of Gyeongju. The Tong-ni·Mogwol Literary Center is a shared space which commemorates the two authors’ literary achievements. It was established in Gyeongju (close to Bulguksa Temple) because it is the hometown of both. The writers’ joint memorial society is responsible for holding a variety of events in their honor. These events—including an essay contest on April 19th, followed by a Pak Mogwol musical performance held at the Gyeongju Arts Center on the 29th, and a children’s song competition on May 2nd at Seorabeol Culture Hall—were all held in Gyeongju.

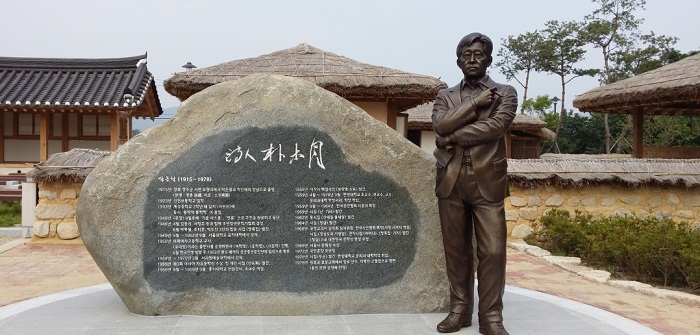

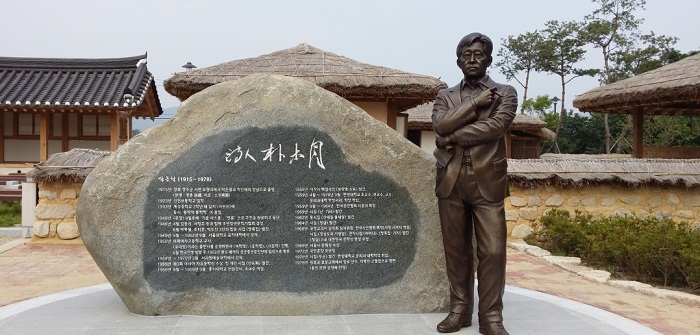

It was particularly poignant that, on July 17th, readings of Mogwol’s poetry and a performance of traditional music were held at the home where he was born, which had been restored in 2014. Mogwol’s birth home is located in Gyeongju-si, Geoncheon-eup, Moryang-ri. The buildings, including the main house, front building, treadmill (foot powered mortar) area, and poetry recitation room were restored, and a boulder engraved with Mogwol’s life story and a statue of the poet were set up as a place to take pictures.

The Tong-ni·Mogwol Memorial Society published a special 100th Anniversary edition of the Tong-ni·Mogwol literary quarterly magazine titled “Shedding New Light on Mogwol’s Literature” and are currently working on having 100 of Mogwol’s poems translated into English, Japanese, and Chinese. Simsang, a poetry journal founded by Mogwol in 1973, is currently published by Mogwol’s eldest son, Seoul National University Professor Emeritus Park Dong-Gyu together and Simsang Publishers. They held a special event on May 30th for the opening of the “Pak Mogwol Literary Park” in the Yongin Moran Park located in Gyeonggi-do Yongin-si where Pak Mogwol’s grave can be found. It was during the opening ceremony that Professor Park Dong-Gyu announced the plan to publish a handwritten poetry collection comprised of eighty of his father’s handwritten poems.

When his students think of Pak Mogwol, their first thought is of his “Big, Soft Hands,” which doubles as the title of his posthumous poetry collection. This is because, while he was strict in matters of education and poetry, Mogwol had a warm and tender, human side as well. All of the events held nationwide in his name over the past year have not only commemorated his literary success, but have been meaningful for the many people who carry fond memories of his warmth.

Article from the List Magazine published by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea

As a nature poet, drawing on and embodying the sensual realities humming in nature and metaphysical meaning, he is best remembered as part of the Cheongnokpa (Green Deer Group) which was born out of the three-poet anthology published in 1946 and entitled Cheongnokjip (Green Deer Collection), which was also Pak’s first published collection of poetry. In this work there is a strong undercurrent of a specific form of purely lyrical methodology running throughout.

The subject matter of Pak Mogwol’s early poetry is nature. However, rather than being a physical kind of nature where the principle of survival of the fittest rules, or an agricultural, bucolic kind of nature, it is nature transformed, so to speak, in the imagination of the poet, reflecting his attitude and outlook on life. An examination of poems such as “Blue Deer” or “April” which are typical of his early works, shows that such a hypothesis is highly convincing. The settings of these poems such as “Cheongun Temple on a faraway Mountain,” “Jahasan,” and “a remote peak/the wind laced with pine pollen” are not so much realistic descriptions of locations in Korea. Rather, they are nature imagined, projected with archetypal ideals to accompany characters such as a “blue deer” and a “blind young woman,” who are the real focus of the poems.

This perfectly intact, imagined world of nature is continually transformed and reproduced in lines such as: “Every wine-mellowing village/ afire in the evening light,” from “The Wayfarer,” and “The mountain/ Gugangsan/ a rocky violet-tinged mountain,” from “Wild Peach Blossoms 1.” This nature, then, becomes something which, shaking off the dust of the everyday world, people can seek without constraint, and be held within its warm embrace. In this way, the nature that appears throughout Mogwol’s early poetry is not inherently the real nature of the agricultural world, but an image of ‘Eden’ conceived of by the poet’s own longing for the divine, the source of all things. Therefore, when the blind young woman in “April,” “puts her ear to the lattice door/ and listens,” it alludes both to the sound of nature and at the same time to the “sound of silence” as an imagined model of divinity.

Towards the middle of his career, Mogwol turned his focus to the sphere of everyday life and, in particular, the communal unit that is the “family.” At the same time, through the substantiality of life and death, his poems sang of earthly love. Consider “Lowering of the Coffin,” which, through the narrator’s eulogizing his own flesh-and-blood younger sibling, allows the soul of the deceased to depart—a masterpiece that expresses devoted love and compassion. The dark heavy image of descent in lines such as: “The coffin was lowered by ropes/ as if into the deep well of the heart,” “world where snow and rain comes down,” and “when fruits fall” acts both to evoke the death of the younger sibling as it happened and to allow us to feel the depth of the narrator’s inner sorrow. In particular, the onomatopoeia of “jwa-reu-reu” and “tuk” appear as vehicular language making the distance between life and death tangible. Here the ropes serve the purpose of lowering the coffin, but they also act as a sort of link between the impassable boundary that divides life and death, and thus the ropes become a means of transmitting the love felt by the living. Therefore, the ropes lower into “the deep well of the heart.”

Another masterpiece, “Family,” expresses the exhaustion of life and a boundless sense of pity for one’s family and oneself. In a home on this Earth live “nine pairs of shoes, different sizes.” Here the walls built of “snow and ice” by the head of a household, who has walked back home along a path of snow and ice, are tangible. However, the reaction to this life of pity appears as “the smile on my face.” Even though it is a life of “treading a way of humiliation and hunger and cold”—this is melted away by the warmth of ardent love.

In “Song of Farewell,” on the other hand, Mogwol reacts to the physical event of death, bringing in the impossibility of communication between the space that separates “you” on the far banks of the river and “me” at the prow of a boat. The “river” separates the two, with one in this world and one in the next world. The narrator on this side of the river can hear a voice coming from the other side, but with the wind blowing it is impossible to make out the meaning of what is being said, and “my” voice asking of the meaning is blown asunder by the gale. A rope that is eroding and weakening is the tie which once bound “you” and “I” in this life. Even if the connection between the two in this life is over, their ties in the next world are something that cannot be known and so we hear the following lines: “Let’s not depart, let’s not depart/ the tie is the wind that crosses the reed bed.” “Let’s not depart” is both “your” words that “I” cannot hear, and a parting greeting from deep down in the narrator’s heart. This is why the narrator responds, “Alright. Alright. Alright./ If not in this world at least in the next...” In the end, through the event of death, this poem actually serves to create affirmation and a philosophical view of life, while also displaying the adaptive quality of the poet’s imagination.

In Mogwol’s later poetry, while still addressing the concreteness of everyday life, he also leans towards ontology and a broader outlook upon life. In his later work, traces of the discipline of his early poems, characterized by linguistic craftsmanship and implication, become difficult to detect, and through an increasingly prose-like form of poetry, Mogwol’s spiritual position is clearly marked out. For example, in “Empty Glass” the poet shows us a self that longs for the emptiness that in fact represents a state of being full to the brim. The “empty glass,” therefore, represents a pure and ordered life. However, the narrator says, “But there cannot be in this world/ things that are empty and void.” This is because “you” do not leave it to be empty. No matter what, “If not filled/ with cool resignation/ it is filled with the water of faith.” Here “cool resignation” represents a self-awareness of human limitations, and it is only then that resigned affirmation of the providence of a higher being can begin. If it is not with coolness, then the empty glass is filled with something soft and warm like the absolute “water of faith.” In this way, God’s providence is not something the narrator has any say in, but is rather a form of grace that he must accommodate unconditionally. Of course such self-awareness is not based on rational principle but on religious experience.

In “Epiphany” for instance, the poet alludes to the experience of a miracle which took place beside the Pool of Siloam as recounted in the New Testament, where eyes that see things “just as they are” refers to the importance of being able to sense the ethereal. This is both a form of self-discipline for a worldly being enraptured by empty desire and a record of introspection regarding the futility of myopic ardor. In the end, in the poetry of his later years, Mogwol shows the stance of accepting a “you” which is completely other, singing of unlimited affirmation for the “absolute being” which pre-exists one’s own life and consciousness.

Continuing the Legacy of Mogwol’s Lyric Poetry

Pak Mogwol was an active poet for forty years, from his debut in 1939 until his death in 1978, and during this time he was a great mentor who guided many poets along their intended path. These poets came together and founded an organization called the Mogwol Literature Forum. The Forum has organized various events to commemorate the centennial anniversary of Pak’s birth, and published a poetry collection, Lonesome Hunger, in memoriam. A total of forty poets contributed to Lonesome Hunger, and surveying the members of the group, we can see that they are the major representative poets in Korean poetry circles.

Actually, Pak’s students, the poets belonging to the Mogwol Literature Forum, can be classified into different groups. First of all, there are the poets from the 1960s who debuted in prominent literary journals through Pak’s recommendations. Second are the poets who debuted in Pak’s professional journal, Simsang, which began publication in 1973. Finally, there are the poets who studied with him during his career as a professor at Hanyang University and then made their debut, even if this did not involve Pak’s recommendation.

Only by understanding the uniquely Korean recommendations process, the way in which writers are inaugurated into the writing community, can one truly understand that later generations of poets write to carry on his legacy. Passing through the recommendations system is the special way that poets and novelists join the literary community and launch their writing careers. In fact, the Korean words for “literary community” (mundan) and “joining the community in one’s literary debut” (deungdan) are characteristically Korean in that they imply a degree of exclusivity. This exclusivity means that one cannot become a poet or novelist without first being recognized by an already established poet or novelist.

This distinctive method by which authors debut is either through the recommendations system (chucheonjae) in the case of literary journals, or the annual spring literary contests (sinchunmunye) in the popular dailies. The two systems have different names and differ slightly in their methods, but they are ultimately alike in that through them an established writer recognizes the work of a new writer. For this reason, writers usually assume “junior” or “senior” status in the Korean writing community according to the year in which they debut rather than with reference to age. By extension, terms such as “poets of the 60s” and “poets of the 70s” also classify poets largely according to the year they debuted. As the debut system was at one time relatively strict, writers had to be recommended three times before they had completed the process. Also, new writers were permanently stamped with the mark of the writer who recommended them in a particular journal, and this recommendation also became a yardstick for evaluating their ability. Therefore, if writers received Pak’s recommendation, it meant that they were esteemed as being the most talented at the time.

The recommendations system came into being in 1939 in Munjang, a journal that was forcibly shut down by the Japanese colonial government in 1941. Pak was among the poets who debuted in Munjang, in 1939. At that time, he received a recommendation from the poet Chong Chi-yong and was published in the journal. It is a well-known story that Chong gave Pak the highest praise, mentioning him together with Kim Sowol in his recommendation letter: “Just as the North had Sowol, it is natural that the South would have Mogwol.” Although many poets debuted in Munjang, the ones remembered together with Pak Mogwol are Pak Tu-jin and Cho Chi-hun. This is because the three of them are known in literary history as members of the Green Deer Group (Cheongnokpa), named after their book of poetry and illustrations entitled Green Deer Collection (Cheongnokjip) published in 1946, the year after Korea was liberated from Japan. In fact, we could say that the journal Munjang was the agent of fate bringing the group together.

The first group of poets that has extended Pak’s legacy debuted in literary journals or in the spring writing contests in the 1960s or 1970s, owing to Pak’s recommendation. Lee Jung was the first poet so honored. After that came Heo Young Ja, Kim Jong-hae, Lee Seung-hoon, Kim Young-jun, Yu An-Jin, Park Geon-han, Jeong Min-ho, Kim Jun-sik, Lee Geon-cheong, Oh Sae-young, Yu Seong-u, Cho Jeonggwon, Na Tae-joo, Lee Chae-gang, Shin Dalja, Lee Geun-shik, Kim Myong-bae, Seo Young-su, Shin Gyu-ho, Jeong Ho-seung, Yu Jae-young, and Yun Seok-san. These poets debuted in magazines such as Hyundae Munhak until the early 1970s. A number of the poets mentioned above also studied with Pak at Hanyang University: Lee Seung-hoon, Park Geon-han, Lee Geon-cheong, Yu Seong-u (graduate school), and Yun Seok-san (Yun was not directly recommended by Pak, but can be counted as a student from Pak’s early period).

The second group debuted in Simsang, the journal Pak published beginning in 1973. The poets included in this group are: Kim Seong-chun, Han Gwang-gu, Lee Jun-gwan, Kwon Taek-myeong, Kim Yong-beom, Han Gi-pal, Kwon Dal-ung, Lee Myeong-su, Jo U-seong, Mok Cheol-su, Yun Gang-no, Lee Eon-bin, Lee Sang-guk, Hwang Geun-sik, and Shin Hyeop. These were the major poets at the forefront of the poetry scene in the 1970s. Some of them also studied with Pak at Hanyang University: Kim Yong-beom, Kwan Dal-ung, Jo U-seong, and Mok Cheol-su.

Pak Mogwol died in 1978, so it was impossible for anyone to receive his recommendation after that. The third group of poets—Park Sang Chun and Lee Sang-ho—were not directly recommended by Pak, but studied Korean Language and Literature with him at Hanyang University and debuted in the early 1980s. This was the last generation to study poetry with him in his days as a university professor. Pak’s students and heirs that debuted in the 1970s and 1980s, including the ones mentioned earlier in this paragraph, once formed a group called Simgakgak, and garnered much attention for being leading young poets. Not only that, but the Mogwol Literature Forum poets are all important members of the Society of Korean Poets, and Forum poets Heo Young-ja, Kim Jong-hae, Lee Geon-cheong, Oh Sae-young, and Shin Dalja have also served as president. It is because their teacher, Pak Mogwol, was deeply connected to the organization that his successors could function as important members and become president themselves. Thus we can say that the poets Pak mentored were following their teacher’s example by participating in the society and assuming leadership roles as poets.

Through membership in the Forum, Pak’s students and heirs can take pride in their teacher and be actively involved in the literary community. The members of the Forum all write poetry in their own individual style, but they are alike in that they are Pak’s students, following after their teacher by extending the literary legacy of Korean lyric poetry.

Hearts Pay Tribute to “Big, Soft Hands”

This year marks the 100th Anniversary of the birth of the poet Pak Mogwol. Pak Mogwol, whose given name was Yeong Jong-in, was born on January 6th, 1915. By way of a recommendation from Chong Chi-yong, he debuted in 1939 in the literary magazine Munjang. After his debut, Mogwol published in Cheongnokjib along with the poets Cho Chi-hun and Pak Tu-jin; together they became widely known as the “Cheongnokpa” (Green Deer Group) and were influential in guiding the path of Korean lyric poetry. There is no hesitation in calling Pak Mogwol our “National Poet” because so many of his outstanding lyric poems, such as “The Wayfarer,” “The Mountain Peach,” “April,” and “Song of April,” are held in the hearts of the nation. His students and those who cherish his memory have come together over the past year to celebrate the centennial of his birth with academic conferences, exhibitions, musical performances, and a variety of other events, as well as the publication of a memorial book, CD, and more. These diverse events and commemorative projects happening all over the country were only possible due to the many people who have been missing their “National Poet.”

The various events for the 100th Anniversary of the poet’s birth have been accomplished through the combined efforts of four organizations: the Mogwol Literary Forum, Hanyang University, the Tong-ni·Mogwol Memorial Society, and the poetry journal Simsang.

The first event was a dinner jointly hosted by the Mogwol Literary Forum, Hanyang University, the Tong-ni·Mogwol Memorial Society, and Simsang Publishers. The dinner was held on the anniversary of Mogwol’s death, March 24th, at Literature House Seoul, where around 150 guests, including veteran poets like Kim Jong-Gil, and Mogwol’s former students were in attendance for the event, which covered all aspects of the literary world.

It was at this dinner that the head of the Mogwol Literary Forum, Lee Geon Cheong, made the following summation of Mogwol’s poetry: “In spite of living through the situation where the Japanese Colonial Government had attempted to erase the Korean language, Mogwol’s poetry faithfully expresses elements in Korean lyric poetry that have the feel of our language and an inherently Korean sentiment.” Many poets, such as Lee Keun-bae and Yoo An-Jin also reminisced about Mogwol’s tender side, conveying that he was more than just a literature teacher, he was a teacher of life. Poets including Shin Dalja, Kim Jong-hae, Lee Sang-ho, and Na Tae-joo recited a selection of his poems.

Matching up perfectly with the timing of the memorial dinner, the Mogwol Literary Forum, which is composed of Mogwol’s former students, published a collection of poems dedicated to their teacher titled Lonesome Hunger. This collection includes elegies from forty poets who were either able to debut due to Mogwol’s recommendation or who studied under him at Hanyang University.

Hanyang University is the school that nurtured Mogwol’s students since he was appointed a professor there in 1962. The Hanyang University Museum held a special exhibition in honor of the centennial of his birth. This exhibit, which opened on April 24th and will run through the end of the year, has attracted much attention, not only for being a showcase of Mogwol’s poetic success, but also because it includes letters he sent to his students as well as other personal effects that show his human side. In addition, an academic seminar titled “The ‘Nowness’ and Re-recognition of Pak Mogwol’s Literature” took place on April 25th. This seminar provided an opportunity for six professors, including Yoo Jong-ho, Lee Namho, and Lee Jae-bok, to present papers that shed a new light on Mogwol’s literary works.

Hanyang University also published a number of anniversary books and CDs for the occasion. One was a book titled Paiknam’s Music, Mogwol’s Poetry. “Paiknam” Kim Yeon-jun, in addition to being a composer and one of the founders of Hanyang University, composed several songs during Mogwol’s tenure at Hanyang that were based on his poetry. This book, which shines a light on the two artists’ collaboration, has even more significance for the fact that last year marked 100 years since “Paiknam” Kim Yeon-jun’s birth. A CD containing fourteen traditional Korean-style compositions by Paiknam with lyrics by Mogwol was released to commemorate the book’s publication. In addition to this, a collection of Mogwol’s essays titled The Moon and Rubber Shoes was published to highlight his essay writing skills, and was accompanied by a pictorial CD showing various activities from his years at Hanyang.

The Tong-ni·Mogwol Memorial Society is the organization that, in December 2002, founded the Tong-ni·Mogwol Literary Center in the city of Gyeongju. The Tong-ni·Mogwol Literary Center is a shared space which commemorates the two authors’ literary achievements. It was established in Gyeongju (close to Bulguksa Temple) because it is the hometown of both. The writers’ joint memorial society is responsible for holding a variety of events in their honor. These events—including an essay contest on April 19th, followed by a Pak Mogwol musical performance held at the Gyeongju Arts Center on the 29th, and a children’s song competition on May 2nd at Seorabeol Culture Hall—were all held in Gyeongju.

It was particularly poignant that, on July 17th, readings of Mogwol’s poetry and a performance of traditional music were held at the home where he was born, which had been restored in 2014. Mogwol’s birth home is located in Gyeongju-si, Geoncheon-eup, Moryang-ri. The buildings, including the main house, front building, treadmill (foot powered mortar) area, and poetry recitation room were restored, and a boulder engraved with Mogwol’s life story and a statue of the poet were set up as a place to take pictures.

The Tong-ni·Mogwol Memorial Society published a special 100th Anniversary edition of the Tong-ni·Mogwol literary quarterly magazine titled “Shedding New Light on Mogwol’s Literature” and are currently working on having 100 of Mogwol’s poems translated into English, Japanese, and Chinese. Simsang, a poetry journal founded by Mogwol in 1973, is currently published by Mogwol’s eldest son, Seoul National University Professor Emeritus Park Dong-Gyu together and Simsang Publishers. They held a special event on May 30th for the opening of the “Pak Mogwol Literary Park” in the Yongin Moran Park located in Gyeonggi-do Yongin-si where Pak Mogwol’s grave can be found. It was during the opening ceremony that Professor Park Dong-Gyu announced the plan to publish a handwritten poetry collection comprised of eighty of his father’s handwritten poems.

When his students think of Pak Mogwol, their first thought is of his “Big, Soft Hands,” which doubles as the title of his posthumous poetry collection. This is because, while he was strict in matters of education and poetry, Mogwol had a warm and tender, human side as well. All of the events held nationwide in his name over the past year have not only commemorated his literary success, but have been meaningful for the many people who carry fond memories of his warmth.

Article from the List Magazine published by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea