View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

Novelist Han Kang

On a bitterly cold day in Seoul, I met the novelist Han Kang, whose gaze made me forget about the cold outside. I had always wondered where within this calm and thoughtful person hid her grand and relentless narratives.

Han Kang was born in Gwangju in 1970 and moved to Seoul when she was 11 years old. Right after graduating from university in 1993, she made her literary debut with a poem in the journal Literature and Society. She won a spring literary contest the following year for her short story, “Red Anchor,” marking her emergence as a fiction writer. Since the beginning of her literary career, Han has received extraordinary attention, later becoming known as one of Korea's controversial writers with the publication of "Love in Yeosu" in 1995 and The Fruit of My Woman in 2000. The considerable talent she exhibited in her short story collections sparkled with even more brilliance in her string of novels including "Black Deer" (1998), "Your Cold Hands" (2000), "The Vegetarian" (2007), "Leave Now, the Wind is Blowing" (2010), and her most recent work, Greek Lessons. Han Kang has continued to receive favorable reviews in addition to winning major Korean literary awards, including the Kim Dongri Literature Prize, Yi Sang Literary Award, Korean Fiction Prize, and Today's Young Artist Prize. Although Han is now known as a novelist with a unique and worldly aesthetic, she originally made her literary debut as a poet.

Han Kang: In my freshman year I began to write both poetry and fiction at the same time. Whenever I sat down at my desk, I began by writing a poem or editing one I had written earlier. After spending an hour on poetry, I would then turn my attention to the novel I had been working on the previous night. After I made my debut, I found myself spending a disproportionately greater amount of time writing novels, but there are still those unexpected times when I'm able to write three or four poems a year.

Rather than being known for a sharp wit reflecting contemporary trends, Han Kang, I believe, has a characteristic eye for reflecting on the tragedy and hurt that fundamentally lurk deep in the human psyche. Thus it makes sense that she began her literary career as a poet, because poems require attention to detail, focus, and penetrating insight more than quick wits. Her first story collection, Love in Yeosu, can be viewed as a personal record of discerning insights into a faithless world during the author's youth. It was her first book, created during a period of intensely focused writing just a year after her literary debut. The story collection was so polished and intense that it was hard to believe it had been written by an author in her mid-20s. Perhaps that is why literary critic Kim Byong-ik wrote the following comment in a review of her first book: “I just hope that the author's zeal and gregariousness help her regain her youth.” In comparison to her literary peers demonstrating humor and wit, why was Han Kang so sensitive to the themes of hurt and suffering so early in her career? I sought a belated reply from the author in response to the critic Kim Byong-ik's comment.

Han: Well, at that time I didn't think physical age was so important. It's not as if I intentionally wrote somber stories. Recently I've had the chance to re-read my first story collection while preparing a revised edition for my publisher. Most of the characters appearing in this collection don’t believe in healing or reconciliation, and reject consolation to the very end. Although this causes them to waver, they try to live in the moment. I now realize that this was my honest impression of the world's essence during that period of my life.

“Human consciousness always coexists with darkness, but our voices are heard most clearly in the blackest darkness.”

After the period of so-called realist fiction in the 1980s had passed, some Korean novelists used humor, while others used eloquent verbosity, lyrical aphorisms, and even trivialism to improve the critical response to their writing. In her first published work, however, Han used her penetrating gaze to peel off the veil of ideology and grand causes, revealing the hinterland of lives for all to see. This will and tenacity put Han Kang in rare company in the world of Korean literature. Perhaps that is why her emergence in the mid-1990s was so controversial.

The expectations of readers after the publication of Han's first story collection, "Love in Yeosu," were finally met in 1998 when the author published her first novel, "Black Deer." The novel is a kind of travel epic that begins with a young woman who’s gone missing. This novel considers the issue of heartbreak superimposed upon the rift between individualism and modern zeitgeist. Literary critic Seo Young-chae highly praised the work, commenting, “This novel signals the arrival of a young master, no less.” The many novels following in the wake of "Black Deer" have proven Seo’s comment to be more prophetic than laudatory. Her second novel, "Your Cold Hands," follows a sculptor, who makes plaster life casts, and his consecutive liaisons with two women. The story is about truth and perspective, illuminating people’s inner world hidden behind flimsy masks. After a hiatus of several years, Han Kang published "The Vegetarian," "Leave Now, the Wind is Blowing," and other works in succession, all featuring strong narratives through which the author tenaciously plumbed the depths of life's tragedies. While writing these two books, however, the author herself seems to have experienced pathos firsthand.

Critic Cho Kang-sok and novelist Han Kang

Han: "The Vegetarian" is divided into three chapters from the point of view of three different characters close to Young-hae, with whom they have made the resolution to go strictly vegetarian. As for the question of what vegetarianism symbolizes…this novel grew out of my curiosity over whether a completely innocent human being could exist. The protagonist, Young-hae, resolutely pursues vegetarianism to the end, to the point that she believes she is a plant and refuses to eat at all. In the process of writing this book, my questions concerning violence, beauty, desire, sin, and salvation became fused together. I remember that completing the last chapter, “Wooden Fireworks,” was particularly difficult for me, as I had to use the voice of In-hae, Young-hae's older sister, who was floundering while trying to understand Young-hae and Young-hae’s physical collapse."

"The Vegetarian" was even adapted for the screen. The cinematic version became a sensation for being one of 10 competing Korean films invited to the 2010 The Sundance Film Festival. The same director also used Han Kang's novella, Baby Buddha, as the basis for the film, “Scar,” which was one of the works selected to compete in the San Sebastian International Film Festival.

Han: Because of the sexual content in this novel, I was worried about careless adaptations to film. Fortunately, the director approached the task with sincerity and enthusiasm, so I decided to let the film adaptation go forward after many consultations. I believe the perspective of the film itself was faithful to the original work, but I was disappointed by the film distributor's provocative focus on the film’s sexual elements for the marketing campaign.

The Vegetarian is about the painful relationship between two sisters. It looks at pain over the passage of time and considers the possibility of healing. On the other hand, it examines the possibility of ruin or salvation for those who cling so tenaciously to a dream of transformation. As suggested by the title of a chapter in The Vegetarian, “Mongolian Mark,” the themes in the book seem to have made a personal impression on the author.

Her most recent book, "Greek Lessons," however, gives a quite different feeling from that of her previous works. Han Kang shared an interesting anecdote about the book.

Han: My fourth novel, "Leave Now, the Wind is Blowing," took me about four and a half years to write. After three years of toiling away on the book, I stopped working on it for a year for various reasons. During my time away from it, I wrote about 150 pages in just one month, which constituted a short first draft for Greek Lessons. In fact, "Leave Now, the Wind is Blowing" had great meaning for me personally, but it also consumed much energy. After having written 150 pages of Greek Lessons and published Leave Now, the Wind is Blowing, I thought to myself, ‘How about rewriting Greek Lessons?’ When I had written around 300 pages, I thought, ‘I'd like the story to be just a bit longer,’ so I rewrote it once more, which is how the book reached its present length. While writing and editing Greek Lessons, I felt many moments of quiet abundance. I actually had a harder time once it was published, because I had to come to terms with the fact that I would no longer be writing it. Once a novel is done, the writer must leave that world.

"Greek Lessons" is the story of an instructor of Greek, who is losing his sight, and his student, who is losing her voice. The plot unfolds like a spiral, with each person’s narrative, background, and personal wounds unfolding separately. Toward the end of the story, however, their stories intersect.

Han: I think this novel is the sunniest of which I am capable. I didn't purposefully write it in a positive or heartwarming way. Instead, I found that the story headed toward the light on its own while I was writing it. I realized that I was approaching the light, too. I couldn't tell on my own whether human warmth was indeed warm; there were parts that were so tender and primeval that I couldn't gauge their tenderness on my own. That's how I knew I was getting close. Approaching these areas required me as a writer to remain invisible. As the characters continued to overcome suffering, the novel gradually became more transparent. This was a strange and unforgettable experience for me.

Han says that she first got the idea for "Greek Lessons" from the concept of the middle voice in the Greek language, explained to her by a friend who had majored in Greek.

Han: After receiving a cup from me, my friend Gang-seok explained that the past tense form of the verb “to receive” differs between the cases “I received it and possess it” and “I received it but it was broken or stolen so I no longer possess it.” I found his explanation quite fascinating. I wanted to write a book based on this concept, but I never would have imagined that it would become a novel.

I didn't turn a blind eye to human suffering in "Greek Lessons"; rather, I found the bright spots while writing the story. Now that I think of it, the four characters in Black Deer wavered amidst the suffering they experienced, and it was commensurate to the danger they faced. Ultimately, however, none of them perish and they live to see a dazzlingly bright and calm afternoon. When I completed this novel at the age of 29, I felt as if I had broken through to the other side. Come to think of it, I had the same feeling when I wrote Leave Now, the Wind is Blowing. When the artist Seo In-joo dies under mysterious circumstances, an art critic assumes it was a suicide, and uses her death to mythicize her. However, the artist's friend Jung-hee, who loved her like her own flesh and blood, attempts to get at the truth. Thus the art critic and Jung-hee each try to tell a different story. During this process, questions related to life and death, remembrance and reality, as well as the sacred and the profane struggle violently with each other. In the final scene, Jung-hee, who had been constantly feeble and morbid throughout this struggle, uses her last ounce of strength to crawl out of her burning house, to break through the fire. In "The Vegetarian," which is filled with even more suffering, the story ends with In-hae riding in an ambulance while looking out the window at trees, which look as if they are on fire. When I write novels, in some sense, each work ends up with its own balance of light and dark, but ultimately, I always try to leave the future open for protagonists.

The author's reference to breaking through stood out immediately. Han Kang’s novels get their intensity from observing characters facing problems and pursuing them to the end, until they deeply penetrate the principles underlying their issues. On the other hand, her novels get their breeziness from the sentences themselves, although Han Kang says she feuded with language itself for quite some time.

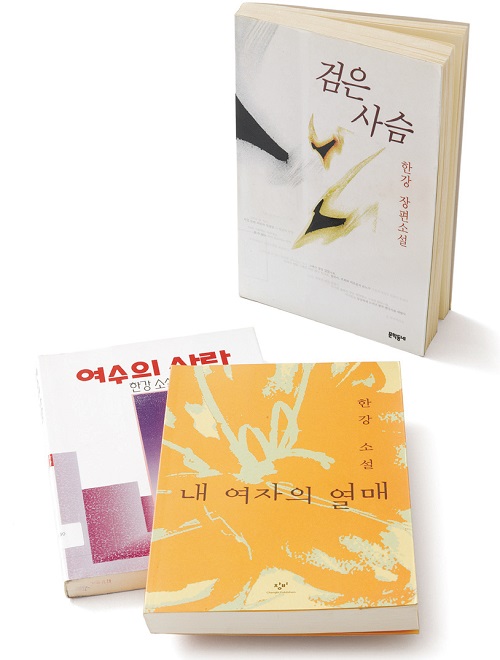

"Black Deer," Munhakdongne Publishing Corp. 2005, 440p (top), "Love in Yeosu," Moonji Publishing Co., Ltd. 2001, 322p, and "The Fruit of My Woman," Changbi Publishers, Inc. 2000, 328p.

Han: In "Greek Lessons," we are introduced to a man gradually losing his sight and a woman who suddenly loses her voice. In the man’s case, it feels as if he is a portrait of the universal everyman. Slowly losing the world of sight and enduring the human condition of the inevitable yet gradual approach of death are one and the same. During the process of mortality, we struggle against death even as our lives are being consumed. This is akin to speech and silence occurring simultaneously. Human consciousness always coexists with darkness, but our voices are heard most clearly in the blackest darkness. During this battle against mortality, our power of speech becomes ragged, and ultimately the female protagonist loses her voice entirely. I think that she could also be a portrait of us all. This opinion reflects my experience of working on Leave Now, the Wind is Blowing for over four years. At that time I became extremely sensitive to language. Rather than conceptual concerns about language, the sensual act of writing itself became unbearable to me. All the words I was using felt like they had become ragged, which pained me. I overcame most of that torment while writing "Greek Lessons."

Han Kang says that she is in the midst of planning two novels; one of them, set in the 1940s, will be her first attempt at historical fiction. She hinted that the book she completes first will likely lean toward the direction she took in Greek Lessons: linguistic intimacy and narrative transparency which, according to the author, “might be viewed as a very personal approach toward breaking through to the light.”

Article from the List Magazine published by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea