View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

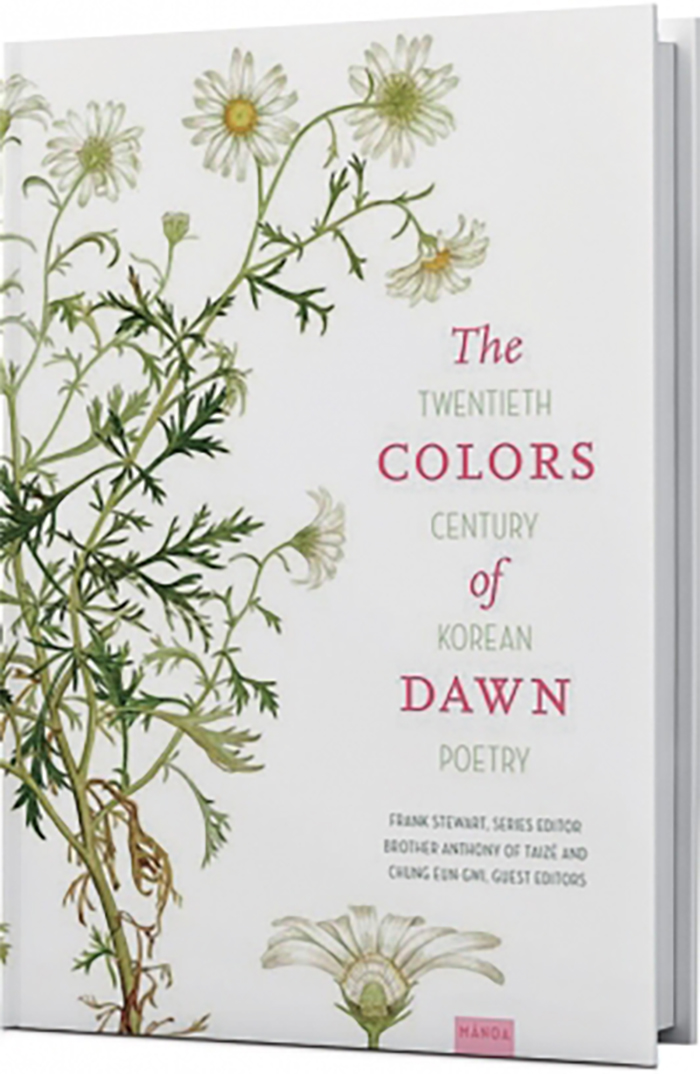

This constellation of new translations necessarily updates our view of Korea’s literary firmament. The collection is structured into three chronologically ordered sections and opens with “Poetry of Today,” containing the work of twenty-one poets (all but one still alive, and the three youngest born in 1970); “Survivors of the War” contains the work of six poets, each of whom is still alive; “Founding Voices” houses the work of seventeen canonical poets. Rather than an independently published anthology in its own right, and despite being a special edition of the esteemed literary journal Mānoa, The Colors of Dawn is a prodigious advance on David R. McCann’s The Columbia Anthology of Modern Korean Poetry (2004). Boldly opening onto vistas of contemporary creative production so as to contextualize those gestures that came before (ethical and aesthetic, stylistic, and thematic), editors Brother Anthony of Taizé and Chung Eun-Gwi have delivered an agenda-setting translation event which seems to seek conversation with the future by speaking equally to both the present and the past.

Make no mistake, the collection carefully valorizes the important legacies of Korea’s early- to-mid- twentieth century poets. Surveying from the New Poetry movement onward, The Colors of Dawn is also greatly assisted by a critical introduction historicizing the poets and their work, situating them within a mesh of mutating social and political conditions. The introduction makes clear how Korean poets have always been in the business of making sense amid the flux and chaos of often-competing shifting ideologies, from occupation and colonization to civil war to military dictatorship to industrialization then rampant neoliberalism and on, to today’s hyper-capitalism. A common point of origin is never far from the gaze of coeditor Brother Anthony of Taizé who, when surveying the era of Japanese occupation, informs his readers how that country’s colonizing plans “entailed the systematic stripping away of Korea’s cultural heritage, beliefs, arts, and, in particular, the Korean language” (p. 13) By scanning the last century’s poetry as both a sovereign artifact and suite of generative modern origins, this collection is a celebration and testament enshrining a pantheon of famously courageous challenges in which poets have spoken back to injustice while imperializing forces visit violence and erasure across the Korean peninsula. Of course, these conditions did not wholly disappear after the Japanese were forced out of Korea; what this collection makes clear is that Korean poetry contains a litany of epic and sometimes tragic engagements, and that a great many poets risked all and some accordingly suffered greatly, or have been successfully silenced, or have disappeared altogether and been lost too early. Some, sympathetic to (or simply silent in the face of) tyranny, bequeath a tarnished legacy: the most famed of these, though, are not excluded from this survey. And while the peninsula has endured more than its fair share of upheavals and ruthless subjugations, this collection is suffused with poems that instrumentalize language, speaking up and out and against authoritarianism. As Brother Anthony asserts: “regardless of their writing styles, ideologies, and aesthetics, [Korean poets] were united in their conviction that poetry was a means to keep their humanity in a world that was absurdly cruel and unjust” (p. 18). Into the early twenty-first century, it seems that while styles have altered (of course), none of these deeper aesthetic urgencies have much changed; as ever, newer poets are making their own desperate ontological maneuvers, employing language as a cutting-edge technology to show us what and how we are, and where we may be heading.

In this highly-structured hierarchical culture (which some have now taken to calling “hell Joseon”), rather than feast on the monoglottal discourses of corporations working to feverish overdrive, the younger poets in this edition of Mānoaseem to choose from an array of transgressive styles; their vaudevillian, satirical, glam, grotesque, surrea l détournements perhaps an ironic critique of the banality of consumption as a mania of excess. Once more we see a generation of Korean poets arriving to take up the cudgel, probing for meaning and value and again undertaking a humanizing enterprise, voicing dissent from within a place many feel to be dehumanizing its inhabitants. In the first half of this collection, then, there is a “Poetry of Today” summoning novel new modes of contrariety as equally interested in engaging the prevailing issues of the day as any of the historical work in Mānoa’s three remaining sections. As per the introduction, the challenge “for today’s poets is to find meaning and value in a world of consumerism, materialism, and self-interest.” (p. 19) The poems that begin this important collection indicate contemporary Korean poets are already and as ever at the forefront of these discourses.

*Article from Korean Literature Now (Vol. 33 Autumn 2016) published by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea

(URL: http://koreanliteraturenow.com/poetry-fiction/tense-pasts-present-futures-contemporary-korean-poetry)