View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

How do poems, as living, breathing, soulful things, seek out and locate their translators?

Whatever the answer, the fact that some of the most important contemporary Korean poetry today has chosen holy men and priestly assistants—Brother Anthony of Taizé and Jake Levine—as its spiritual-linguistic intermediaries seems a matter of supernatural importance.

For this is a holy book. Holy in the sense of the ancient Biblical term and eponymous Ginsberg opus, Kaddish, the Hebrew word for “separation.” Indeed, the speaker of Kim Kyung Ju’s I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World and many of the figures he identifies with are (or were in their times) as separate from the earth as astronauts. While in Kim’s highly animated, animistic world, signs and symbols of holiness abound, in “absolution through beer,” (p. 70) a halo that appears “while cutting a dried earthworm,” (p. 52) even in “the soul of glass,” (p. 64) it is often most evident in the poet’s sense of Otherness:

The only ability I have is the ability to be different than you. (p. 120)

I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World is remarkable for its sophisticated simultaneously musical, philosophical, alchemical inquiry. Kim Kyung Ju often employs Heraclitus’s Union of Opposites to powerful poetic effect:

Like a furnace, the sea began to boil flakes of snow… (p. 53)

His poems are full of evocative inversions and involutions:

The hole that floated around inside my body

seeped out the hole of my throat (p. 63)

It is also a work of uncommon sensory charm and synesthetic appeal:

Inside every sip of water, the smell of a shadow is mumbling

Worried that the well’s long tongue might climb out (p. 65)

Think about that the next time you reach for a drink.

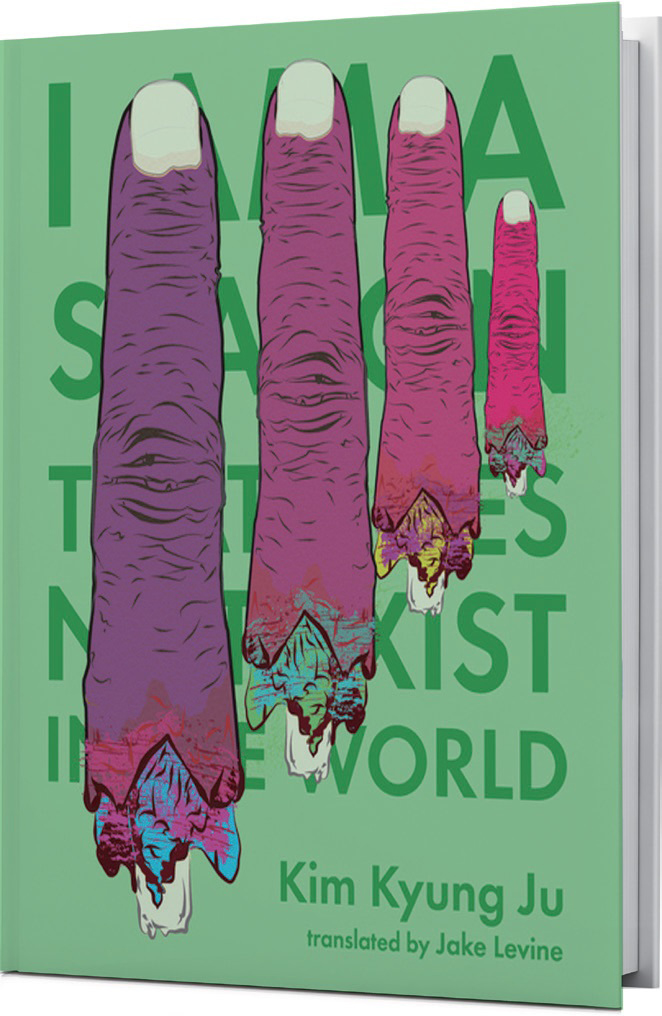

I Am a Season is bursting with graphic dismemberments. It is also replete with images of reproduction and delivery. For in this work the spiritual and visceral go… hand in hand. Thus, the severed fingers—transfigured by the sacred space of creation (womb/theremin)—become religious icons, giving new meaning to digital technology.

This is dismembering in the service of re-membering, though it has more to do with the musical than the mnemonic. According to Paul Valery, poetry is not just a language within a language—it differentiates itself from the ordinary languages it inhabits according to the following equation: the music of its words must be of equal or greater importance than their meaning. Thus, Kim’s book stands as a two-fold project of resuscitation, at once linguistic and existential: to breath poetry back into language, and meaning back into life.

It also contains The History of Underwear.

Every sensory organ in I Am A Season’s orchestra engages to the fullest—especially the olfactory and auditory:

Beethoven didn’t compose music. Beethoven was music.

What he recorded was only his desperation. (p. 114)

This is no sonic reductionism, but the glorious rendition of human particles of being as scored wavelengths. In this light, any images of decomposition serve as present material for the recombination of music.

Because language is no less than… the physics of humanity (p. 123)

It is no accident that Kim composed his book in four movements; it is as much a musical composition as a biopoetic one. We must admire Kim’s determination in undertaking such a project:

The definition of extinction is when the sound of a species disappears.

I will not go extinct. (p. 80)

Often “dreamlike and sad,” the tonalities of his instrument-Other Theremin, much of the work unfolds in darkness reminiscent of Rilke’s, with whom he shares many leitmotifs, including death, ghosts, and loneliness. Kim’s studies of the ocular organ (e.g., “I admit my eyes have not yet been born” p. 107) mirror Malte Laurids Brigge’s constant refrain, “I am learning to see.” Thus, as a nocturne, its notes of lightness, grace, and hope emerge all the more resoundingly:

Although one by one snowflakes disguise the lights of a town

there is love, love on the side of the planet we can see

here, undiscovered, infinity. We divvy up our shares. (p. 54)

A poet and playwright of phenomenal range, Kim conveys empathy through down-home intimacy and connectedness:

Dudes, yer all on the same team. (p. 71)

In the aphoristically rich fourteen-page poem “A City of Sadness,” Kim displays Goethe-Eckermann-inspired Donald Barthelme-wit:

Childhood is the renaissance of life. If I were Muslim, I would bow to the Mecca called childhood six times a day. (p. 111)

A book of diverse influences, the deeply emotional back cover excerpt on the thwarted expression of fossilized love resonates with Emerson’s words from “The Poet”:

The poets made all the words, and therefore language is the archives of history, and, if we must say it, a sort of tomb of the muses. For, though the origin of most of our words is forgotten, each word was at first a stroke of genius… Language is fossil poetry.

Kim Kyung Ju ’s inspirational, revitalizing book is also a stroke of genius. Masterfully, delightfully rendered into English by Jake Levine, I Am a Season That Does Not Exist in the World is cutting edge, and demands the attention of readers, critics and artists the world over.

*Article from Korean Literature Now (Vol. 33 Autumn 2016) published by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea