By Jeon Han

Photos = Yonhap News

Illustration = Manus Eugune

"One who should not be forgotten by Koreans even for a single day."

This is what freedom fighter Ahn Jung-geun, who was imprisoned in 1909 at Lushun Prison in China after assassinating Hirobumi Ito, the first Japanese resident-general of Korea, said in response to a question from a Japanese police officer about Homer Bezaleel Hulbert (1863-1949).

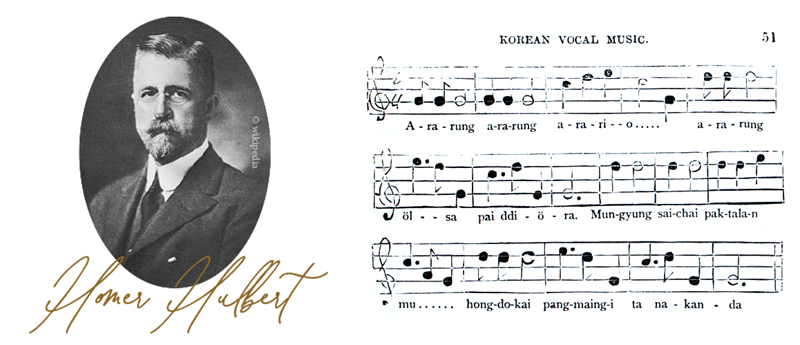

Hulbert was the first foreigner to receive a public funeral in Korea in 1949 and earn the Order of Merit for National Foundation, which was awarded to him posthumously the following year. Given his legacy and the traces he left behind, it is no wonder why many independence fighters revered the American and why he was dubbed the "person who loved Korea more than Koreans."

The ceremony for the 69th anniversary of Homer Hulbert’s death was held on Aug. 10 at Yanghwajin Foreign Missionary Cemetery in Seoul's Mapo-gu District. Pro-independence patriot Lim Woo-chul bows his head in a silent tribute after giving a floral offering.

Learning about Korea and Hangeul

Hulbert began his relationship with Korea as a teacher at the Royal English School in 1886. Learning the Korean language and Hangeul immediately after arriving in Joseon (Korea's name at the time) for missionary work and education, he provided support from 1890 for the compilation of A Concise Dictionary of the Korean Language along with British American pastor and educator Horace Grant Underwood (1859-1916) and Canadian missionary and educator James Scarth Gale (1863-1937).

Hulbert's affection for Korea grew through learning the Korean language, and he expressed his fondness for the country through his books and theses. Having published a world geography book in Korean in 1891, he publicized the excellence of Hangeul in his paper "The Korean Alphabet," which was published in the first issue of The Korean Repository, the first English-language monthly magazine in Korea, in January 1892. He also submitted an article on how Hangeul was invented in the magazine's March issue in the same year and another on idu, a writing system that represented the Korean language through the sounds and translations of Chinese characters, in the February 1898 issue.

Returning to the U.S. in 1891 and coming back to Korea with his family in 1893, Hulbert devoted himself to writing about Korea including its culture, society and history and his missionary work through numerous documents. He took over Sammun Publishing Co. in 1893 and resumed the suspended publication of The Korean Repository. Aside from publishing English-language magazines and books on missionary work, Hulbert was the de facto editor in providing relevant knowledge and printing equipment when Seo Jae-pil (1864-1951) began publishing the daily The Independent in April 1896.

This is a copy of an interview with Homer Hulbert, a foreign policy adviser to Emperor Gojong, who announced that the emperor did not sign the Japan-Korea Treaty of 1905 and that the royal seal was stolen. This interview was published by The New York Herald on July 22, 1907.

Secret envoy of Korean Empire

Hulbert used to guard the bedroom of Emperor Gojong nightly along with Underwood after the Eulmi Incident, which saw Miura Goro, the Japanese minister to Korea, take the lead in assassinating Empress Myeongseong on Oct. 8, 1895. Armed with a pistol, Hulbert escorted Gojong at the time of the Chunsaengmun Incident, in which the emperor, who was under constant threat, tried in vain to go to the American legation in Korea with the help of pro-American Koreans on Nov. 27, 1895.

As Japan began acting on its ambition to colonize the Korean Peninsula, Hulbert in 1905 pleaded with Gojong to take action. Eventually, the emperor gave the American a confidential letter underscoring the Korea-U.S. friendship, clarifying Japan's acts of aggression and the corresponding injustice, and asking for America's help. Hulbert tried everything but ultimately failed to deliver the letter to U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919).

After the conclusion of the Eulsa Treaty, which forcibly deprived Korea of its diplomatic sovereignty in November 1905, Hulbert denounced the agreement, saying, "The U.S. handed Korea to Japan."

Failing to deliver Gojong's letter and seeing how imperial Japan distorted news about Joseon, Hulbert concentrated on publicizing Korea by publishing in 1906 The Passing of Korea, a book on many aspects of the country including its geography and background, race, political system, history, industry, culture, arts, social systems, modernization and future.

When the International Peace Conference opened in The Hague in 1907, Hulbert was dispatched as the emperor's secret envoy to publicize Japan's atrocities and greed to the representative of each country.

The traditional folk song "Arirang" was introduced to the West by Homer Hulbert, who published the score for "Munkyung Saejae Arirang" in Korea’s first English-language journal The Korean Repository.

Unprecedented Honors for Non-Korean

Hulbert continued his activities for Joseon, and this ultimately prevented his return to the peninsula because of Japan. He lashed out at U.S. policy toward in his adopted country in his contribution "American Policy in the Case of Korea and Belgium" in the March 5 edition of The New York Times in 1916, and exposed Japan's cruelty in Korea through his statement "What About Korea" to the U.S. Senate in August 1919 after the March First Independence Movement occurred on March 1 of the same year.

Attending the so-called Korean Freedom Congress in Washington in 1942, Hulbert testified that Japan forcibly colonized Joseon, saying, "Emperor Gojong was always bullied but never gave up the country."

Hulbert's activities for Korean independence continued until national liberation in 1945. At age 86, he returned to Korea on July 29, 1949, under the invitation of President Syngman Rhee. Before passing away on Aug. 5 that year, only a week after returning to Korea, Hulbert left a will reading, "I would rather be buried in Korea than at Westminster Abbey." He was laid to rest at Yanhwajin Foreign Missionary Cemetery in Seoul after his public funeral.

Hulbert's son William, in a contribution sent in 1973 to commemorate the Korean-language publication of his father's book, conveyed his dad's everlasting love for Korea. "My father never gave up hope that even after 40 years, Korea would be liberated from Japan and be a free and independent country after World War II,” the younger Hulbert said, adding, "(If he saw the peninsula's division), I am certain that my father's hope for a unified Korea would overcome such adversities as this and that he believed that they would build a glorious and dazzling future."

hanjeon@korea.kr