View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

Korean psychological thriller author You-Jeong Jeong talks about The Good Son, her first book translated into English, at a book launch event in London."

By Korea.net Honorary Reporter Diya Mitra from the U.K.

Photos = Diya Mitra

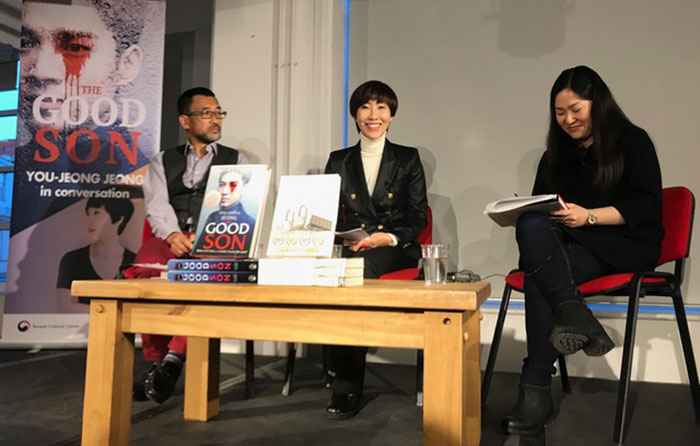

I had the honor of moderating in October last year a discussion of You-Jeong Jeong's novel The Good Son, her first work translated into English. I was excited to hear that the author was coming to London from Korea for a book launch event with Asia Literary Review editor Phillip Kim and Grace Koh, a lecturer of Korean literature at SOAS University of London, at the bookstore Foyles Charing Cross London.

Having read the novel earlier in the year, I was struck by its sense of intrigue, complexity of familial relationships, detailed imagery of the blood and guts spattered throughout the story and the interweaving flashbacks that play with the reader's sense of understanding from a rather unreliable narrator.

In addition to The Good Son, Jeong has written five other novels. Her first, My Life’s Spring Camp (2007), won the Segye Youth Literary Award. Her second novel was Shoot Me in the Heart (2009) and her third Seven Years of Darkness (2009). Her fourth novel was the popular 28 written in 2013 and then came The Good Son (2016). Her second and third novels have been made into movies and The Good Son is set to be her third work to make it on the silver screen.

Seven Years of Darkness sold more than 500,000 copies and The Good Son climbed to the top of the bestseller list before its release, as pre-orders soared on Korea’s major online bookstores. In a poll conducted by the country’s largest bookstore Kyobo Book Centre, The Good Son was voted the best fiction work of 2016.

Jeong has taken an unusual road in achieving writing success. Born in 1966 in Hampyeong-gun County, Jeollanam-do Province, she spent her formative years studying at the Christian College of Nursing in Gwangju. She then spent five years as a nurse in an intensive care unit and nine years at the Heath Insurance Review and Assessment Service. She had always wanted to pursue a literary career but waited until her early 40s due to her mother’s objections. She then began writing short stories and entered competitions, and on her 12th try, she won a prize.

Her entry into literature is all the more commendable given her route into the profession was rather an unusual one. In Korea, an aspiring author generally needs to have formally studied literature or creative writing, learn from a mentor and be in a literary environment. Even then, one is not considered a writer until he or she wins a prize.

The following are excerpts from an interview with Jeong conducted by Kim professor Koh at the book launch event.

- What was your inspiration for writing The Good Son and can you tell us a little more about the title?

The Korean title of the novel is different (from the English one) as it was published as The Origin of Species in Korean. The English title was chosen by the publisher after consultations with the translator and myself.

I've always been interested in questions about human evil and psychology. The specific inspiration for the story was a real-life event in Korea in 1992. Back then, the country was still in a developmental stage and not as affluent as it is now, with the term "psychopath" not widely known or recognized in society. One small community that was affluent within the Gangnam district of Seoul were the "nouveau riche," who could send their children abroad to study. These spoiled kids were running amok, earning them the nickname orenjijok (orange clan), a term was related to Orange County, California. It became a buzzword at the time.

A young man sent abroad to study by his rich but hardworking parents developed a gambling problem. He accrued huge debts and when his father found out, you can imagine how shocked and disappointed he was in his son and called him good for nothing. The son became enraged and stabbed his parents to death, his father 40 times and his mother 50 times. He then set their house on fire. At their funeral, he laughed and showed no sense of guilt or remorse. Throughout their investigation, detectives found it difficult to corroborate his story as it was never consistent each time he told it. When he was discovered to have committed the crime, it became headline news in Korea. Filial piety is huge in our country, so this was an unprecedented event in modern Korean history. How inconceivable it was that someone could act in such a callous way toward their parents, let alone take their lives.

I remember how shocked I was when I heard the news. I'd lost my mother in my 20s and simply couldn’t understand how someone would want to kill their parents. There was a time where I'd cry simply by watching ads depicting a mother-and-daughter relationship, as I missed my mother so much. To understand why someone would want to do this, I started reading Carl Jung and Sigmund Freud to learn more about criminal pathology and psychology. I had to read Korean-language versions of these works since they hadn't been written in Korean originally. I really wanted to write about this topic.

- Given the taboo nature of the topic you wrote about, how was the book received in Korea?

I was nicknamed "Amazon" in Korea when my novel debuted, as it was a completely new kind of novel, the first of its kind. Literary critics, however, were enraged by my book, with many critics and writers saying I wrote it for commercial gain and to boost my popularity. This wasn't my intention but commercialism isn't an entirely a bad thing in my opinion. But I was heavily criticized and ignored. Interestingly, the book was well received by readers and the general public as they considered it something new. It opened up a new genre in Korean literature.

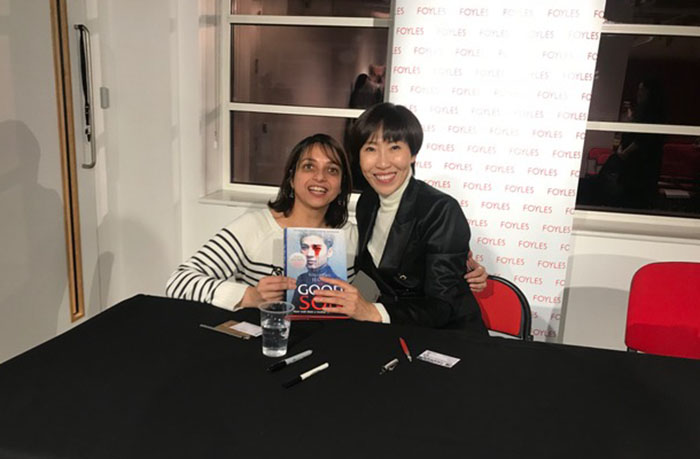

Korea.net Honorary Reporter Diya Mitra (left) poses for a photo with Korean novelist You-Jeong Jeong after a book launch event for The Good Son in London.

- Some people have nicknamed you the "Stephen King of Korea," and you've said before that he has greatly influenced your work. Do you think the comparison is because of similar subject matter or writing style?

Imagine, if you will, two places: a sunny wide open field and a forest. In the forest, beasts and creatures are hidden within. In the case of Stephen King, he writes about the depths of the hidden forest using the method of suspense. So when people compare me to him, I get compared with this method of storytelling. As I didn’t study or major in literature unlike many other writers, I had no mentor to guide me. In some ways, writers like King and Raymond Chandler were my mentors. I love their works and was inspired and influenced by their storytelling methods. I feel King has taught me the ABCs of writing.

While I'm extremely honored and humbled to be compared to (King), I also feel I'm committing blasphemy because he is such a god-like figure.

- This novel delves deeply into the mind of a psychotic killer. How much of this person is in you? How did you set about doing this?

Any novel contains the writer's inner elements. This book took three drafts before I got what I wanted. I think the reason the first two drafts failed was because I simply mimicked what I'd studied. For my third and final draft, I had to really get into the mind of a psychopath and become like one. I went to the extent of scaring my husband, who asked if I could live or sleep elsewhere. I think about Freud when he said everyone has dark dreams and those who exhibit normal behavior won't let these dreams surface or act on them. If someone has a horrible altercation with his or her boss, he or she might dream of killing the boss but most will never act on it. To be a psychopath is to carry out these sorts of actions. The frightening thing was that I felt at peace when acting this way, but I spent three months recuperating in France living as recluse to recover after finishing the novel.

The reason I can do this is largely because of my personality. I'm quite fearless and resilient thanks to my mother raising me to be a strong individual. I also have an innate sense of survival that allows me to study the darker side of human nature without falling apart.

- Four years ago, when Korea was the market focus at the London Book Fair, I remember being asked as a panelist whether Korea had genre fiction. It wasn't something common or popular in Korea at the time but things seem to have changed since. What do you think of the label and genre of crime fiction?

When I was submitting my works to competitions (in Korea), fantasy, thrillers and crime didn’t exist as genres. When I won a prize, it caused a bit of a sensation as it was the first work of its kind to receive an award. Some younger writers say I drove a tank through (the Korean literary scene) and raised a flag for these categories to exist in Korea.

- You've written two or three crime thrillers, one that is apocalyptic in nature, 28. What are you working on now?

I do have other works in progress and it’s looking like one will be published in May. In genre, I would largely describe it as a work of fantasy and my first book to feature a woman as the protagonist, a chimpanzee trainer. Overall the novel's theme is death. My mom's untimely death early in my life remains one of my biggest tragedies. It's a trigger for me. I worry over not being able to see my son again and all that goes with the idea of personal extinction. This idea has always consumed me. This project makes me think about and confront this idea of death. Death is a depressing subject, but I aim to present it in a captivating way. Choosing a female protagonist is a good way to explore this topic, as I feel that women are generally more mature and I can explore this theme through this character. The challenge is that I lack femininity and am generally considered a bit of a tomboy. My readers, who are mostly male, call me hyeongnim, a term usually reserved for males referring to older males. It means "older brother" and they consider me an honorary man. But since I announced that my new work has a female protagonist, I've been branded a traitor.

- How important is it for you to depict strong female characters?

I do believe that it's important to have strong characters alongside the protagonist. They help fuel the narrative and act as a plot device. My mother was a strong woman and a so-called tiger mom. I was never allowed to say I couldn't do or achieve something. She did this out of love to make me a strong woman. To me, a strong woman is someone who is like my mother. I've been criticized by readers for creating female lead characters who are too aggressive or scary.

- What other challenges did you face while writing the third draft of this novel?

I often get asked this question and always answer that it was a challenging time for me. But this was the first time in my life that I did things that I wouldn't have done before while living as a psychopath, and it was surprisingly very liberating for me. It might sound scary but I really got to understand the psychopathic mind and why they do what they do and could sympathize with them. To consider thinking this way is dangerous. But I think being a writer is a great profession as it gives me the opportunity to explore this and write about it, but return to a sense of normalcy at the end of the day.

wisdom117@korea.kr

* This article is written by a Korea.net Honorary Reporter. Our group of Honorary Reporters are from all around the world, and they share with Korea.net their love and passion for all things Korean.