- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

By Honorary Reporter Zana Bulteel from Belgium

Photos= Zana Bulteel

A group of Korea.net Honorary Reporters on Aug. 5 visited the National Museum of Korea after the facility was reopened last month. The government's quarantine efforts allowed all cultural facilities in the Seoul metropolitan area to be reopened to the public after their temporary closure due to COVID-19. To ensure visitor safety, the museum uses an online reservation system and limits the daily number of visitors. To mark its reopening, Honorary Reporter Zana Buteel from Belgium wrote this piece on the history and significance of Korean printing techniques, which can be learned more in depth at the museum.

Many in the West are taught that Johannes Gutenberg of Germany invented the printing press in 1439. Yet nearly 600 years before him, Korean and Chinese monks employed a printing method using wooden blocks to spread Buddhism through printed versions of drawings and texts. Traditionally, the two main printing types in East Asia have been woodblock and metal movable type.

The woodblock technique was used in Korea from the eighth century to produce Buddhist texts and drawings, dating back to the Silla Dynasty (B.C. 57-935). By the 16th and 17th centuries, just a few Buddhist texts were being published by the government since neo-Confucianism had taken over in the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). Buddhist temples across the Korean Peninsula thus took the initiative to produce their own books though the woodblock method. In the belief that spreading Buddhism would help the people continue doing good deeds, monks kept printing sutras, texts and drawings while carrying on the woodblock tradition.

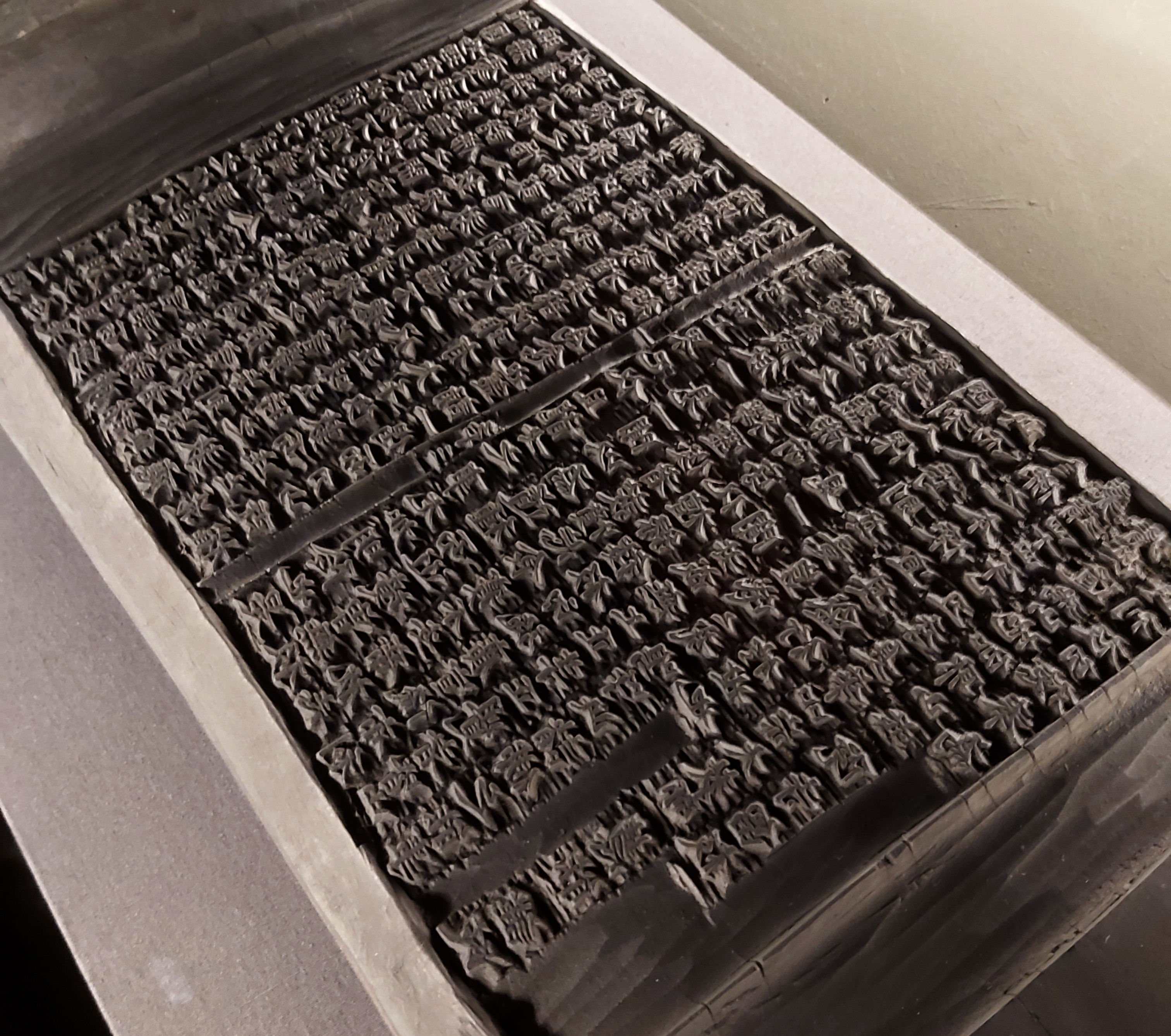

This delicate technique was done exclusively by a master in applying ink on letters carved from wooden blocks. The paper was put face down and pressed on a wooden plate. The woodblocks usually consisted of two handles on the ends to protect the plates and sometimes were categorized by their respective functions. Chaekpan was the book plate used for the main topics of a book, seopan was utilized as a practice book for calligraphy, neunghwapan for illustrations on a book's cover, inchalgongchaekpan as a notebook and dopan for diagrams.

What makes Korea's woodblock printing different from others was that compared with manuscripts printable only once because of their uniqueness, the Korean editions had distinctive characteristics such as letter sizes that could be reproduced. Woodblock prints also varied by period, offering a clear window to examine social changes throughout Korean history through assessment of the dissimilar scripture styles and shapes of the woodblocks.

The movable metal type was invented by a Chinese peasant in the 11th century. The board was assembled with letters needed for a page to be printed, a technique that slowly came into use during the 12th century. The Korean Buddhist monk Baegun (1298–1374), whose Buddhist name was Gyeonghan, used movable metal type in the late 14th century to print a compilation of Buddhists texts that were later bundled into the two-volume book "Jikji" (1377). Literally translated as "Anthology of Great Buddhist Priests' Zen Teachings," "Jikji" was printed during the Goryeo Dynasty (918-1392) and remains the world's oldest surviving book printed through movable metal type. UNESCO confirmed the work as the oldest of its kind by including it on the list of the Memory of the World Programme.

If the movable metal type was invented in Asia hundreds of years before Gutenberg's version, why didn't the Asian edition make it to Europe? The first reason is that Asian writing systems are far more complex than those of Europe, comprising hundreds to even thousands of characters. Second, Korea suffered numerous invasions during its history, and this limited the dissemination of Korean innovations. Furthermore, Koreans used Hanja (traditional Chinese characters) based on Chinese and thus used a larger number of characters than they do now. Production and assembly of the letters on pages were also an incredibly slow and tedious process. And finally, the Goryeo Dynasty limited the availability of the movable metal type to the nobility after its invention, so a large number of prints were unnecessary.

Though Gutenberg and his printing press deserve commendation, I want to express my admiration and fascination for these two printing techniques that were revolutionary for their times. As a writer, I am deeply fascinated by this extraordinary way Buddhist monks printed their stories in the hope of spreading words of wisdom and love.

To learn more about other Korean heritage hidden in delicate landscape drawings or elegant poems, visit the National Museum of Korea in Seoul. Reopened on July 22 after being temporarily closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the museum is holding an exhibition of these glorious woodblocks and even prints.

chaey0726@korea.kr

*This article is written by a Korea.net Honorary Reporter. Our group of Honorary Reporters are from all around the world, and they share with Korea.net their love and passion for all things Korean.