Should visitors to the Seoul National Cemetery make their way to the patriots section of the cemetery, they might be surprised to see a foreign name among the tombstones. Francis Schofield, however, is known to many in Korea as the “34th man,” a reference to the 33 patriots who signed the declaration of Korean independence on March 1, 1919, a move which set off the March 1 Independence Movement.

Earlier that year, as peace was being negotiated following the end of World War I, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson made a speech which, at one point, called for self-government in all conquered territories. Inspired by this, Korean students in Korea and Japan began to organize a protest movement to call for Korean independence after a decade of Japanese military rule.

The only foreigner to be informed of the protest before it took place was Francis Schofield, a Canadian medical missionary working and teaching at Severance Medical School. He was visited by Yi Kap Sung, a member of the 33 patriots and an employee of the school, in February and asked if he would aid the independence activists. While the other missionaries and foreigners in Korea were surprised by the protests, Schofield was instead dashing about Seoul taking photos of the protests, photos which almost every Korean today has seen.

Schofield also personally intervened in the protests, walking up to policemen who were taking away demonstrators and demanding that they release his “servant,” a ploy which worked for some time. Once police caught onto this, he used the police chief’s business card to gain entrance to Seodaemun Prison, where he observed the ill treatment the prisoners were receiving in their overcrowded cells. He even had a chance to see Yu Gwan-sun, the well-known high school student who was to die a martyr in the following year due to mistreatment in prison. Being a doctor at Severance Hospital, he also saw first-hand the injuries inflicted upon demonstrators by sword-wielding Japanese police officers.

Schofield may be best known, however, for bringing to light the Jeam-ri Massacre which took place in Hwaseong County, Gyeonggi-do (Gyeonggi Province) on April 15, 1919. On that day, Japanese forces drove around 30 Koreans into the village church and set it on fire, shooting anyone who tried to escape the flames. The village was just one of many in the area burned to the ground by Japanese soldiers. When Schofield heard rumors of the massacre, he took his bicycle aboard a train and, after shaking a police tail, made his way to the village where he interviewed survivors and photographed the destruction he found.

Angered by what he saw, Schofield sent letters to local newspapers trying to inform the public of the brutality of the Japanese authorities in Korea. In a November 1919 letter to the Japan Advertiser, he criticized Japan’s “damnable policy of assimilation” and asked, “Is there any morality in a policy which makes 17 millions of people hopeless, and at the best offers exile or jail for Korea’s noblest men and women?”

Due to government control of information, few outside Korea knew the truth of what was happening. The Japanese English-language propaganda newspaper, the Seoul Press, carried an article about Seodaemun Prison which painted it in the rosiest of colors. In response, Schofield wrote a sarcastic letter, telling the paper that, “We foreigners were very glad to read such a cheerful and beautiful picture of the prison, because we have always thought that there were many prisoners jammed into a small room, bitten by parasites, starved and in rags. Contrary to our misconceptions, our Korean friends are said to have technical lessons, a cheerful atmosphere, and frequent baths. What a wonderful piece of news!”

Though the Seoul Press replied that, “The letter from a foreigner confirmed that foreigners are unduly suspicious of us,” suspicion ran both ways. Schofield’s actions, which included cataloguing the brutality he witnessed, did not go unnoticed by the Japanese authorities. In December 1919, the Governor-General of Korea stated, “That Christian missionaries are behind the disturbances in Korea is an undeniable fact and a man named Schofield, belonging to the Severance Hospital at Seoul, is one of the most pronounced types of these agitators.”

As it turned out, it was not the Japanese who ousted him from Korea, but debate over his political involvement in Korea which led the Presbyterian mission which sent him to demand his return home. In the end, it was his refusal to stay ”politically neutral” that led to his abrupt recall by the Presbyterian mission in 1920.

Returning home to Canada, he engaged in pioneering work in veterinary science at the Ontario Veterinary College in Guelph, Ontario, where he continued to write letters to the local paper decrying the racial discrimination he had found in his own country.

In 1958, after almost 40 years in Canada, he returned to Korea and taught at Seoul National University and Yonsei University. He also helped run two orphanages and even supported students who hoped to study abroad with scholarships at his own expense. Among the students he helped was future Prime Minister Chung Un-chan, whose middle school tuition was covered by Schofield.

As current Canadian Ambassador to Korea David Chatterson relates, “People have very strong memories, fond memories of Dr. Schofield and his contributions to Korea. Quite often I’ll mention his name and people will go ‘Oh yeah,’ and start telling a story they've heard or to which they're directly related."

The Korean government recognized Schofield’s efforts and awarded him the Order of Cultural Merit in 1960 and the Independent Medal of the Order of Merit for National Foundation in 1968. When he passed away in 1970, he was given a public funeral and became the first foreigner to be buried at Seoul National Cemetery.

By Matt Van Volkenburg

A member of the Royal Asiatic Society, Korean Branch

Discover Korea with the RAS

[The Royal Asiatic Society Korea Branch, founded in 1900, is an association of people, Koreans and non-Koreans alike, who wish to deepen their knowledge of Korean life, culture, and history, and share that knowledge with others in English. http://www.raskb.com/]

Earlier that year, as peace was being negotiated following the end of World War I, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson made a speech which, at one point, called for self-government in all conquered territories. Inspired by this, Korean students in Korea and Japan began to organize a protest movement to call for Korean independence after a decade of Japanese military rule.

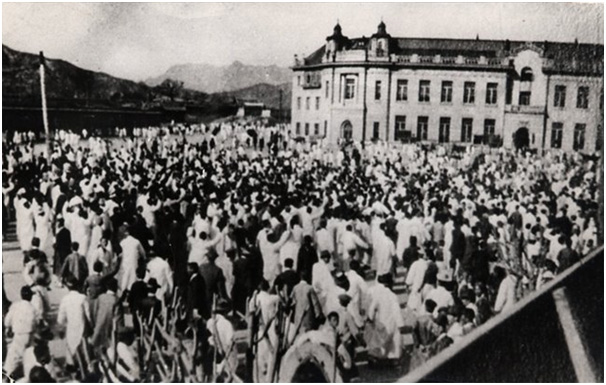

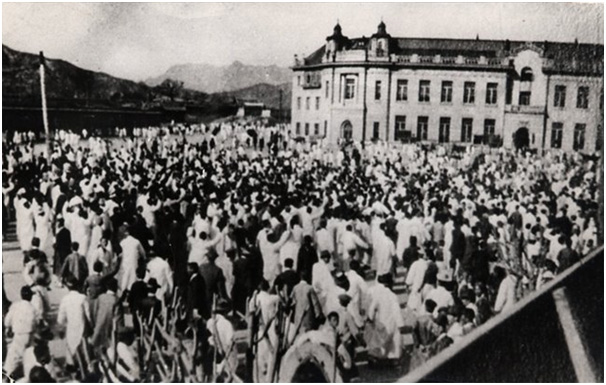

The only foreigner to be informed of the protest before it took place was Francis Schofield, a Canadian medical missionary working and teaching at Severance Medical School. He was visited by Yi Kap Sung, a member of the 33 patriots and an employee of the school, in February and asked if he would aid the independence activists. While the other missionaries and foreigners in Korea were surprised by the protests, Schofield was instead dashing about Seoul taking photos of the protests, photos which almost every Korean today has seen.

Demonstrators participate in the March 1 Independence Movement. (Photo courtesy of Matt Van Volkenburg)

Schofield also personally intervened in the protests, walking up to policemen who were taking away demonstrators and demanding that they release his “servant,” a ploy which worked for some time. Once police caught onto this, he used the police chief’s business card to gain entrance to Seodaemun Prison, where he observed the ill treatment the prisoners were receiving in their overcrowded cells. He even had a chance to see Yu Gwan-sun, the well-known high school student who was to die a martyr in the following year due to mistreatment in prison. Being a doctor at Severance Hospital, he also saw first-hand the injuries inflicted upon demonstrators by sword-wielding Japanese police officers.

Participants in the March 1 Independence Movement were taken to Severance Hospital after acts of police brutality. (Photo courtesy of Matt Van Volkenburg)

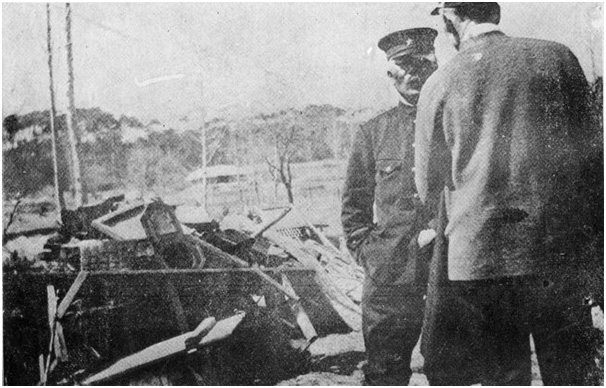

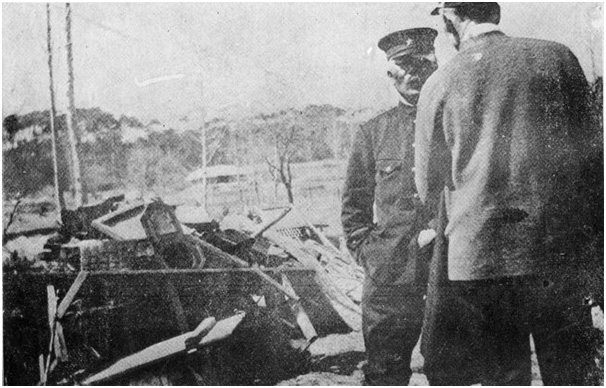

Schofield may be best known, however, for bringing to light the Jeam-ri Massacre which took place in Hwaseong County, Gyeonggi-do (Gyeonggi Province) on April 15, 1919. On that day, Japanese forces drove around 30 Koreans into the village church and set it on fire, shooting anyone who tried to escape the flames. The village was just one of many in the area burned to the ground by Japanese soldiers. When Schofield heard rumors of the massacre, he took his bicycle aboard a train and, after shaking a police tail, made his way to the village where he interviewed survivors and photographed the destruction he found.

The scene of the church burnt down by Japanese forces. (Photo courtesy of Matt Van Volkenburg)

Angered by what he saw, Schofield sent letters to local newspapers trying to inform the public of the brutality of the Japanese authorities in Korea. In a November 1919 letter to the Japan Advertiser, he criticized Japan’s “damnable policy of assimilation” and asked, “Is there any morality in a policy which makes 17 millions of people hopeless, and at the best offers exile or jail for Korea’s noblest men and women?”

Due to government control of information, few outside Korea knew the truth of what was happening. The Japanese English-language propaganda newspaper, the Seoul Press, carried an article about Seodaemun Prison which painted it in the rosiest of colors. In response, Schofield wrote a sarcastic letter, telling the paper that, “We foreigners were very glad to read such a cheerful and beautiful picture of the prison, because we have always thought that there were many prisoners jammed into a small room, bitten by parasites, starved and in rags. Contrary to our misconceptions, our Korean friends are said to have technical lessons, a cheerful atmosphere, and frequent baths. What a wonderful piece of news!”

Though the Seoul Press replied that, “The letter from a foreigner confirmed that foreigners are unduly suspicious of us,” suspicion ran both ways. Schofield’s actions, which included cataloguing the brutality he witnessed, did not go unnoticed by the Japanese authorities. In December 1919, the Governor-General of Korea stated, “That Christian missionaries are behind the disturbances in Korea is an undeniable fact and a man named Schofield, belonging to the Severance Hospital at Seoul, is one of the most pronounced types of these agitators.”

Matt Van Volkenburg

As it turned out, it was not the Japanese who ousted him from Korea, but debate over his political involvement in Korea which led the Presbyterian mission which sent him to demand his return home. In the end, it was his refusal to stay ”politically neutral” that led to his abrupt recall by the Presbyterian mission in 1920.

Returning home to Canada, he engaged in pioneering work in veterinary science at the Ontario Veterinary College in Guelph, Ontario, where he continued to write letters to the local paper decrying the racial discrimination he had found in his own country.

In 1958, after almost 40 years in Canada, he returned to Korea and taught at Seoul National University and Yonsei University. He also helped run two orphanages and even supported students who hoped to study abroad with scholarships at his own expense. Among the students he helped was future Prime Minister Chung Un-chan, whose middle school tuition was covered by Schofield.

As current Canadian Ambassador to Korea David Chatterson relates, “People have very strong memories, fond memories of Dr. Schofield and his contributions to Korea. Quite often I’ll mention his name and people will go ‘Oh yeah,’ and start telling a story they've heard or to which they're directly related."

The Korean government recognized Schofield’s efforts and awarded him the Order of Cultural Merit in 1960 and the Independent Medal of the Order of Merit for National Foundation in 1968. When he passed away in 1970, he was given a public funeral and became the first foreigner to be buried at Seoul National Cemetery.

By Matt Van Volkenburg

A member of the Royal Asiatic Society, Korean Branch

Discover Korea with the RAS

[The Royal Asiatic Society Korea Branch, founded in 1900, is an association of people, Koreans and non-Koreans alike, who wish to deepen their knowledge of Korean life, culture, and history, and share that knowledge with others in English. http://www.raskb.com/]