By Etsuro Totsuka

International human rights lawyer

March 26 this year marks the 110th anniversary of the execution of Lieutenant General Ahn Jung-geun of the Korean Righteous Army.

The pro-independence fighter assassinated Japanese Resident-General of Korea Hirobumi Ito on Oct. 26, 1909, at Harbin Railway Station in China. Ahn was arrested and thrown into Lushun Prison. He was sentenced to death on Feb. 14, 1910, and he was executed weeks later on March 26.

Despite Ahn killing their own leader, many Japanese say they respect and admire him for his personality, leadership and capability as a great thinker and even his artistic talent.

Yet how do Korea and Japan evaluate him today? In Korea, he is considered a hero of the independence movement, but in Japan, he is seen as a terrorist who killed Ito. Is this evaluation correct?

The biggest legal problem with this issue is the question of whether the Guangdong Provincial District Court had jurisdiction under Japanese colonial rule. The judge of the court at the time ruled that the Japanese consul in Harbin, China, had jurisdiction based on Clause 2, Article 1, of the 1905 Protectorate Treaty between Korea and Japan, known as the Eulsa Treaty, which was concluded on Nov. 17, 1905. Also known as the Japan-Korea Protectorate Treaty or the second Japan-Korea Treaty, the agreement gave the Japanese foreign ministry the rights of diplomacy and protection of its nationals in the Korean Empire. The judge basically condemned Ahn to death by applying Japanese criminal law to a Korean prisoner. The verdict, however, had major flaws from a legal perspective.

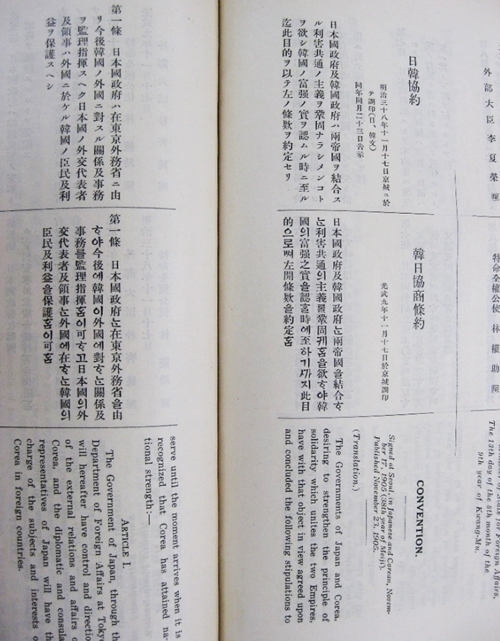

The photo shows the Japanese-, Korean- and English-language texts of the Eulsa Treaty signed on Nov. 17, 1905. This is page 204 of the third volume that is related to Joseon and Ryukyu and part of "The Compilation of Old Treaties (舊條約彙纂)." The volume was published by the Treaties Bureau of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs and is owned by Kyoto University. (Etsuro Totsuka)

According to an International Law Commission report submitted to the United Nations Assembly in 1963, the treaty was involuntarily signed by the Korean emperor and his cabinet under threat from Japan. From the perspective of international law, this makes the treaty indisputably null and void. Thus as a result, the Japanese court had no legal grounds to have jurisdiction at the time.

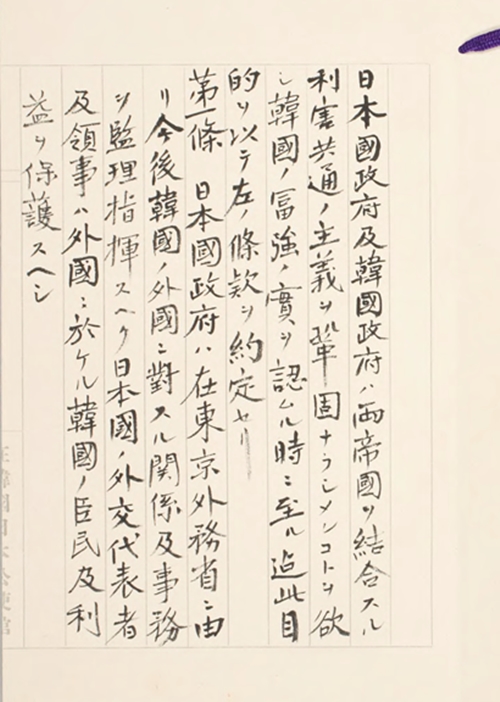

The bigger issue, however, is pointing out the illegality of the trial. In short, the Eulsa Treaty does not exist. In the original Japanese-language version of the treaty kept by the Japanese government, the first line is empty, and even the treaty’s title is not written. Thus it is nothing but an early draft of the agreement and a far cry from the final version.

Even if the treaty exists, another problem arises: the lack of even the signature of the supreme leader or ratification.

The original Japanese-language version of the Eulsa Treaty signed on Nov. 17, 1905, is stored at the Diplomatic Archives of the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (www.jacar.go.jp/goshomei/index.html) (Etsuro Totsuka)

For this reason, Korea has argued that the Eulsa Treaty is null and void. The Japanese side, however, alleges that it is possible in international law for two nations to sign a treaty in which one of them transfers diplomatic power and loses independence to the other without ratification.

In 1905, all Japanese scholars of international law urged the need for ratification, with no publication saying it was unnecessary. After 1905, several theories unconvincingly claimed that ratification was unnecessary. This is because based on the logic of transitional law, a theory made after a treaty is signed cannot prove its validity at the time of signing.

The treaty, which served as the basis for the jurisdiction of the trial of Korean independence activist and martyr Ahn Jung-geun, does not exist. The trial was also conducted illegally without the right of jurisdiction. Thus Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga was legally incorrect in 2014 when he said Ahn's act constituted the crime of murder under Japanese criminal law and dubbed him "a terrorist."

In the trial, Ahn argued that his assassination of Hirobumi Ito was an act for the regaining of his country's sovereignty as a lieutenant general of the Korean Righteous Army. Therefore, he said he deserved proper treatment as a prisoner according to international law. He demanded a trial to judge whether his act was a war crime. But the Japanese court ignored him. Ahn also did not file an appeal with a higher court, and thus his death sentence was confirmed.

Ahn should be considered the general of a righteous army who fought for his country's independence against Japanese aggression. Though he was sentenced to death, labeling him a terrorist holds no water. Furthermore, the 1910 Annexation Treaty between Korea and Japan can be also seen as null and void because the agreement's conclusion was based on the Eulsa Treaty.

Both Korea and Japan must now bolster collaboration and joint research to share the gist of the Eulsa Treaty.

Etsuro Totsuka is a Japanese human rights lawyer who has actively championed human rights and world peace for more than 40 years. In 1992, he became the first person to raise the issue of forced labor mobilization and sex slavery by Japan with the U.N. Human Rights Committee as a member of the nongovernmental organization International Educational Development.

Translated by Korea.net staff writer Yoon Sojung.