| The following op-ed was written by Nam Sanggu, research fellow at the Northeast Asia History Foundation in Seoul, and published by The Asia Times on June 28, 2020. Korea.net has received the author's permission to publish his article. |

By Nam Sanggu, research fellow

Northeast Asian History Foundation

What the Japanese government promised

On July 5, 2015, the 23 sites of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution related to iron, steel, shipbuilding and coal mining were designated World Heritage by the World Heritage Committee (WHC) of UNESCO. At the time, the WHC recommended that Japan prepare "an interpretive strategy" to allow an understanding of the full history of each site. Tokyo accepted this advice and pledged to take measures "to allow the understanding that a large number of Koreans and others were mobilized against their will and forced to work" under harsh conditions. The history that the Japanese government acknowledged is nothing new, as this material is even in textbooks for elementary, middle and high school students in Japan.

This signboard is at Hashima Coal Mine, one of Japan's Meiji Industrial Revolution sites. (Nam Sanggu)

Tokyo breaks promise, attempts to whitewash history

In the five years since making its pledge, however, the Japanese government has reneged on its promise. Visitors to each of the 23 Meiji sites can find the same information signboard that mentions nothing of Japan's mobilization of forced laborers. Japan accepted the wave of the Industrial Revolution from the West to lay the foundation for its entry into modernization, and proudly told of its success of being the only non-Western country to achieve world-class industrialization.

Yet Japan's industrialization is deeply related to its past war of aggression. As the result of its industrialization, Japan used its shipbuilding technology to make battleships and iron and steel-making know-how to make cannons, and used coal as fuel. In the end, Japan used all of these resources to invade many Asian countries. The Japanese government in 1955 announced a prime minister's statement apologizing for and reflecting on Japan's aggression that damaged many people in Asian countries. Incumbent Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe also said he will carry on the statement. After the 23 Meiji industrial sites were designated UNESCO World Heritage, however, Japan stealthily changed its attitude toward history from remorse over its past wrongdoings to pride.

In mid-June this year, the Japanese government opened to the public the Industrial Heritage Information Centre. The center's exhibition shows nothing about how Japan mobilized workers from Korea, China or other countries or prisoners of war from Allied nations caught in Southeast Asia and forced them to work at coal mines under harsh conditions such as starvation. The center only shows the testimonies of Hashima Island islanders who denied any discrimination against such workers occurred.

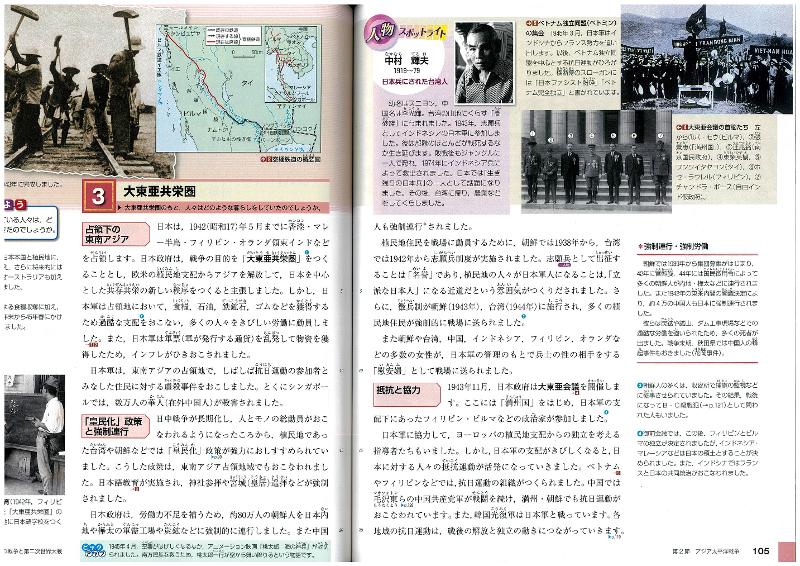

A high school history textbook published by Jikkyo Syuppan in Japan explains the nation's forced mobilization of foreign workers. (Northeast Asia History Foundation)

Global indifference spurs change in Japan's attitude

Did the lack of reviewing historical facts eventually lead Japan to break its promise made in 2015? Or was it failure to find witnesses to the damage? First, the facts are written in Japanese school textbooks. Testimonies from witnesses have been published, and the victims have filed lawsuits against Japanese companies. This information is thus readily available if searched for. So why has Japan broken its word? The WHC's 21 member countries in 2015 all paid attention to Japan's attitude. Five years later, however, they seem to take no interest in such attitude today. This indifference allowed Japan to change its stance.

Broken pledge poses challenge to UNESCO

UNESCO was established to reflect on the devastation caused by the two world wars and prevent a recurrence. The World Heritage system was set up to preserve the heritage of universal values as common assets of humankind. Because Japan's industrial facilities are designated UNESCO World Heritage, they cannot become tools to beautify Japan's history. This poses a challenge to the meaning of UNESCO's very existence.

Need to listen to historical facts and create common memories

The best weapon against Japan's challenge is to listen to historical facts. The history of Japan's industrial heritage must also be written and remembered together. If the Japanese government fails to keep its word, we must make it do so. This is a right and responsibility for all of us.

Earning his Ph.D. from Japan's Chiba University in 2005 for his research on Japan's remembrance of wartime victims, Nam since 2007 has studied historical conflict and reconciliation in Northeast Asia at the Northeast Asian History Foundation in Seoul.

Translated by Korea.net staff writer Yoon Sojung.