Some sports coverage on a TV at a noodle restaurant has changed the life of an American, completely.

As an anthropologist, the American was in Korea in 2006, collecting data for his doctoral thesis on inmaek, personal connections. Just one day before he left for his home country, he happened to watch a ssireum competition on TV at the noodle restaurant.

Ssireum is a traditional Korean sport, similar to wrestling. It was like love at first sight. The American man instantly fell in love with the way the sport was played.

It’s a story of Professor Christopher Sparks at Yeungnam University. What fascinated him about the sport is its rules: The first person who has any part of his or her body from the knees up touch the ground, loses.

It’s a story of Professor Christopher Sparks at Yeungnam University. What fascinated him about the sport is its rules: The first person who has any part of his or her body from the knees up touch the ground, loses.

Even when he got back home, he couldn’t stop thinking about the sport. He started scouring the Internet for information on ssireum and tried to get any available data. The more he got to know the sport, the more he got immersed in it.

He even changed the subject of his ongoing dissertation into ssireum. After six years of research into the sport, he completed his thesis titled, “Wrestling with Ssireum” and got a Ph. D. at Texas A&M University in 2011.

The next year, he was appointed Professor of Kinesiology at Yeungnam University in Gyeongsangbuk-do (North Gyeongsang Province) and has since dedicated the expertise he has accumulated over the years to helping students learn what the sport is really about.

Last March, the ssireum aficionado gathered up all the data he has collected over those years and published the English-language book, “SSIREUM- The Living Culture.”

The 217-page volume is somewhat of an encyclopedia that encompasses everything about ssireum, from its history and transition into a modern sport, all the way through to its techniques.

He translated all the commentaries and technical terms into English. For example, he terms satba, a cotton cloth that each player wraps around the waist and the thigh, as “belt” in English.

One of the technical skills is apmureupchigi, a term he interpreted as “front knee takedown” and then juxtaposed with its Romanized transliteration.

“To globalize ssireum, I tried to use as easy English as possible so as to help non-Koreans easily understand the sport,” said Sparks.

Korea.net recently visited his office to hear more about his passion and love for ssireum.

- When and how did your full-blown love affair with ssireum begin?

It was a gradual process. The first time I saw ssireum, I was curious about it. The more I tried to talk to people about ssireum, the more interested I became as an anthropologist. And then after I had come back to Korea and spent a year in the industry I really developed a personal connection to it. During the course of the year I went to every ssireum competition in the country to collect data.

- Your main study in anthropology used to be "inmaek,” or personal connections. How did you come to switch to ssireum?

It was a natural transition. Originally I came to look at networking and understand the ways that people form social bonds. The idea for that project came from the variety of experiences my Korean friends had in the States – some people were good at maintaining existing social bonds, but poor at creating new ones and those people always had a hard, if not impossible, time establishing careers outside of Korea.

The change happened when I got curious about ssireum and it developed into an even more exciting research topic, though I’m still interested in inmaek. In fact, inmaek is really at the heart of ssireum. Ssireum is something that unites people and forms a community. It’s a thing people do “together.” That’s why we call it a “folk sport.”

Actually we can see people, whether players or spectators, talking to each other like friends. There’s a friendly atmosphere at every ssireum competition. I believe that if you come to a competition, you can expand your inmaek. I hope you go and check it out.

- How did people around you -- friends or family -- react when you introduced the sport to them, a sport that is perhaps unfamiliar to many people and which, moreover, is extremely rare to be promoted by a non-Korean?

It’s still difficult to share ssireum with people outside of Korea because there is a dearth of readily available information in English. Actually, as far as I know I’m the only person to write about it as such. We need to develop readily accessible media to help introduce ssireum to people. We want people to hear or read the word “ssireum” and then develop some awareness about it.

I teach classes that have both Korean and international students in them. I do my best to get people to actually attend a competition and the reaction is always a unanimous, “Wow, this is awesome!” There’s something primordial in the attraction of watching people grapple up close. It’s a kind of “muscular theater.” It hits you deep in the brain. And it’s totally different than just seeing it on television. That’s the biggest challenge -- getting people exposed in person. Once you do that, they’re hooked.

The truth is that anthropologists are supposed to walk the line between “insider” and “outsider.” Immersion is how we get good, rich data and distance is how we keep the objectivity to analyze that data well. You need both to do your job right. If you look at my book, you’ll see that balance.

I think as time goes by you’ll see more people able and willing to give their voices to ssireum in ways that everyone can appreciate.

- What do you think it is that distinguishes ssireum from other traditional sports?

I hesitate to talk about the essential features of ssireum because, as history shows, they’re subject to change. Whatever we focus on today could well be different tomorrow. That’s the way culture works. I prefer to focus on “continuity” instead -- the ways that aspects of culture are maintained regardless of changes in their forms and what that means in society.

Wrestlers wear special belts called satba that they grip during competition. This directly influences how they play because it creates a vocabulary of technical skills and rules that define competition at present. But it would be wrong to focus on the satba alone. We need to understand what it means. In this case, wearing a satba means that even when a wrestler topples an opponent, both of them end up falling to the ground. That imparts a very unique value -- to win in ssireum, you must be willing to fall. I don’t know of too many other sports with that particular aesthetic.

- Are there any other goals you want to challenge, what with your deep insight into the sport?

The most important things in my mind are expanding opportunities to play and attend competition. We need to increase the number of teams in primary and secondary schools, we need to create elite women’s teams, we need to attract foreign players, and we need to make it easier for people to see competitions with their own eyes. As a social phenomenon, real sport happens in person. It’s about doing something together. We need to get as many people involved in that as possible.

- We find it very interesting that you chose the English-language title, “SSIREUM- The Living Culture.” Please tell us a bit more about the ways in which the sport is a piece of “living culture.”

My point with the title of the book is that ssireum is constantly “evolving.” If you look at how ssireum was probably played during the Joseon Dynasty, it would have very little in common with the modern sport. Yet they’re both somehow still ssireum. The process that sustains that relationship is what I wanted to highlight. Ssireum isn’t trapped in time. It’s always adapting as Korean society changes. It’s too easy for us to hear the word “traditional” and then get a static, immutable image in our mind. I really want the book to work against that tendency and remind everyone that, “Hey, culture exists now.” It’s what we are doing “right now.”

- You must have had one or two difficulties while explaining the sport in English. What were they?

From a technical standpoint, I find the Romanization of Korean to be really technically unwieldy since it doesn’t adequately distinguish between syllables, it can’t easily convey some sounds, and it unnaturally fuses words with distinct grammatical particles. So the next best solution is to opt for translation wherever possible and slog through transliteration when unavoidable.

There are two issues with that however. First, we lose the elegance of the language, especially when it comes to the technical terms that describe motion and direction. Second, we can alienate some purists who feel that translation weakens the identity of the sport. It’s tough to internationalize something so nuanced as ssireum, but we can’t please everyone no matter what we do.

- In your eyes, what does Korea look like? What about the people?

The things I see and experience are unique to my situation, and so they can’t reflect what other people may think about the country or its populace. The years that I have lived in Korea have irrefutably shown me that human beings around the world are remarkably similar when you get down to it. We share the same anxieties and the same aspirations.

Everywhere I went to talk to people and spend time with them just learning about what they do I found them utterly willing to make me a part of that experience. For example, everyone in the Korea Ssireum Association and Yeungnam University was warm and open beyond belief. I developed some lifelong bonds through my work.

- Finally, what does ssireum mean to you?

As an anthropologist, I’ll tell you that ssireum is the people who play it. As one of those people, I’ll borrow from Dr. Sung-han Park and say, “Ssireum means never giving up.”

By Sohn JiAe

Korea.net Staff Writer

jiae5853@korea.kr

As an anthropologist, the American was in Korea in 2006, collecting data for his doctoral thesis on inmaek, personal connections. Just one day before he left for his home country, he happened to watch a ssireum competition on TV at the noodle restaurant.

Ssireum is a traditional Korean sport, similar to wrestling. It was like love at first sight. The American man instantly fell in love with the way the sport was played.

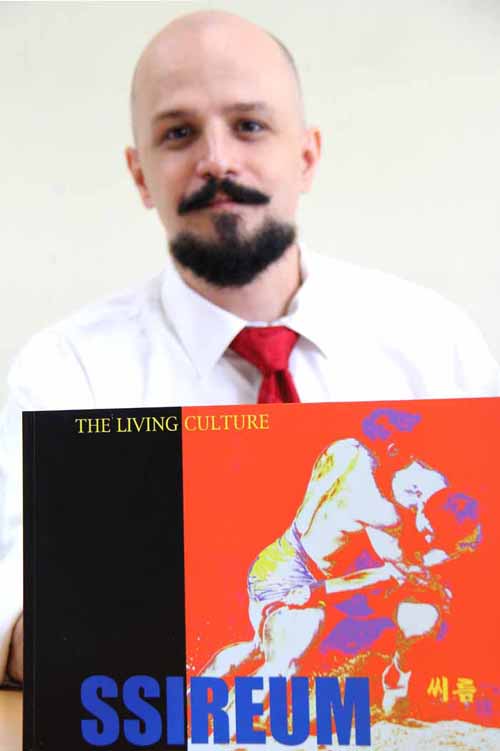

Professor Christopher Sparks poses for a photo, holding his recent English-language publication about ssireum, “SSIREUM- The Living Culture.”

Even when he got back home, he couldn’t stop thinking about the sport. He started scouring the Internet for information on ssireum and tried to get any available data. The more he got to know the sport, the more he got immersed in it.

He even changed the subject of his ongoing dissertation into ssireum. After six years of research into the sport, he completed his thesis titled, “Wrestling with Ssireum” and got a Ph. D. at Texas A&M University in 2011.

The next year, he was appointed Professor of Kinesiology at Yeungnam University in Gyeongsangbuk-do (North Gyeongsang Province) and has since dedicated the expertise he has accumulated over the years to helping students learn what the sport is really about.

Last March, the ssireum aficionado gathered up all the data he has collected over those years and published the English-language book, “SSIREUM- The Living Culture.”

The 217-page volume is somewhat of an encyclopedia that encompasses everything about ssireum, from its history and transition into a modern sport, all the way through to its techniques.

He translated all the commentaries and technical terms into English. For example, he terms satba, a cotton cloth that each player wraps around the waist and the thigh, as “belt” in English.

One of the technical skills is apmureupchigi, a term he interpreted as “front knee takedown” and then juxtaposed with its Romanized transliteration.

“To globalize ssireum, I tried to use as easy English as possible so as to help non-Koreans easily understand the sport,” said Sparks.

Korea.net recently visited his office to hear more about his passion and love for ssireum.

- When and how did your full-blown love affair with ssireum begin?

It was a gradual process. The first time I saw ssireum, I was curious about it. The more I tried to talk to people about ssireum, the more interested I became as an anthropologist. And then after I had come back to Korea and spent a year in the industry I really developed a personal connection to it. During the course of the year I went to every ssireum competition in the country to collect data.

- Your main study in anthropology used to be "inmaek,” or personal connections. How did you come to switch to ssireum?

It was a natural transition. Originally I came to look at networking and understand the ways that people form social bonds. The idea for that project came from the variety of experiences my Korean friends had in the States – some people were good at maintaining existing social bonds, but poor at creating new ones and those people always had a hard, if not impossible, time establishing careers outside of Korea.

The change happened when I got curious about ssireum and it developed into an even more exciting research topic, though I’m still interested in inmaek. In fact, inmaek is really at the heart of ssireum. Ssireum is something that unites people and forms a community. It’s a thing people do “together.” That’s why we call it a “folk sport.”

Actually we can see people, whether players or spectators, talking to each other like friends. There’s a friendly atmosphere at every ssireum competition. I believe that if you come to a competition, you can expand your inmaek. I hope you go and check it out.

- How did people around you -- friends or family -- react when you introduced the sport to them, a sport that is perhaps unfamiliar to many people and which, moreover, is extremely rare to be promoted by a non-Korean?

It’s still difficult to share ssireum with people outside of Korea because there is a dearth of readily available information in English. Actually, as far as I know I’m the only person to write about it as such. We need to develop readily accessible media to help introduce ssireum to people. We want people to hear or read the word “ssireum” and then develop some awareness about it.

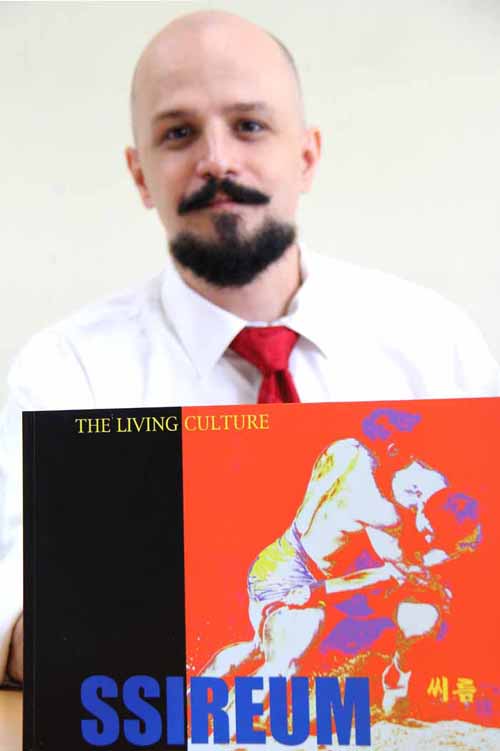

I teach classes that have both Korean and international students in them. I do my best to get people to actually attend a competition and the reaction is always a unanimous, “Wow, this is awesome!” There’s something primordial in the attraction of watching people grapple up close. It’s a kind of “muscular theater.” It hits you deep in the brain. And it’s totally different than just seeing it on television. That’s the biggest challenge -- getting people exposed in person. Once you do that, they’re hooked.

The truth is that anthropologists are supposed to walk the line between “insider” and “outsider.” Immersion is how we get good, rich data and distance is how we keep the objectivity to analyze that data well. You need both to do your job right. If you look at my book, you’ll see that balance.

I think as time goes by you’ll see more people able and willing to give their voices to ssireum in ways that everyone can appreciate.

- What do you think it is that distinguishes ssireum from other traditional sports?

I hesitate to talk about the essential features of ssireum because, as history shows, they’re subject to change. Whatever we focus on today could well be different tomorrow. That’s the way culture works. I prefer to focus on “continuity” instead -- the ways that aspects of culture are maintained regardless of changes in their forms and what that means in society.

Wrestlers wear special belts called satba that they grip during competition. This directly influences how they play because it creates a vocabulary of technical skills and rules that define competition at present. But it would be wrong to focus on the satba alone. We need to understand what it means. In this case, wearing a satba means that even when a wrestler topples an opponent, both of them end up falling to the ground. That imparts a very unique value -- to win in ssireum, you must be willing to fall. I don’t know of too many other sports with that particular aesthetic.

Professor Christopher Sparks describes ssireum, “Muscular theater.”

- Are there any other goals you want to challenge, what with your deep insight into the sport?

The most important things in my mind are expanding opportunities to play and attend competition. We need to increase the number of teams in primary and secondary schools, we need to create elite women’s teams, we need to attract foreign players, and we need to make it easier for people to see competitions with their own eyes. As a social phenomenon, real sport happens in person. It’s about doing something together. We need to get as many people involved in that as possible.

- We find it very interesting that you chose the English-language title, “SSIREUM- The Living Culture.” Please tell us a bit more about the ways in which the sport is a piece of “living culture.”

My point with the title of the book is that ssireum is constantly “evolving.” If you look at how ssireum was probably played during the Joseon Dynasty, it would have very little in common with the modern sport. Yet they’re both somehow still ssireum. The process that sustains that relationship is what I wanted to highlight. Ssireum isn’t trapped in time. It’s always adapting as Korean society changes. It’s too easy for us to hear the word “traditional” and then get a static, immutable image in our mind. I really want the book to work against that tendency and remind everyone that, “Hey, culture exists now.” It’s what we are doing “right now.”

- You must have had one or two difficulties while explaining the sport in English. What were they?

From a technical standpoint, I find the Romanization of Korean to be really technically unwieldy since it doesn’t adequately distinguish between syllables, it can’t easily convey some sounds, and it unnaturally fuses words with distinct grammatical particles. So the next best solution is to opt for translation wherever possible and slog through transliteration when unavoidable.

There are two issues with that however. First, we lose the elegance of the language, especially when it comes to the technical terms that describe motion and direction. Second, we can alienate some purists who feel that translation weakens the identity of the sport. It’s tough to internationalize something so nuanced as ssireum, but we can’t please everyone no matter what we do.

- In your eyes, what does Korea look like? What about the people?

The things I see and experience are unique to my situation, and so they can’t reflect what other people may think about the country or its populace. The years that I have lived in Korea have irrefutably shown me that human beings around the world are remarkably similar when you get down to it. We share the same anxieties and the same aspirations.

Everywhere I went to talk to people and spend time with them just learning about what they do I found them utterly willing to make me a part of that experience. For example, everyone in the Korea Ssireum Association and Yeungnam University was warm and open beyond belief. I developed some lifelong bonds through my work.

- Finally, what does ssireum mean to you?

As an anthropologist, I’ll tell you that ssireum is the people who play it. As one of those people, I’ll borrow from Dr. Sung-han Park and say, “Ssireum means never giving up.”

By Sohn JiAe

Korea.net Staff Writer

jiae5853@korea.kr