-

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel- NEWS FOCUS

- ABOUT KOREA

- EVENTS

- RESOURCES

- GOVERNMENT

- ABOUT US

View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

Ask a Korean the biggest cultural oddities facing a Westerner in his country, and you will likely hear a commentary on terrifyingly spicy food, unfailing reverence for the elderly or the perils of trying to master chopsticks. Ask a Westerner, however, and the list transforms. What the heck is with these devil-may-care drivers? They will demand. Why do older people barge through me as if I didn’t exist? And how can Koreans gather in a small room, and sing and dance with face-twisting abandon?

True enough, noraebang (literally “song room”) as it is known here, is one of those oddities, but it is far from unique to Korea. My earliest brush with it actually took place in Hong Kong, where I lived and worked for three years in the mid-’90s.

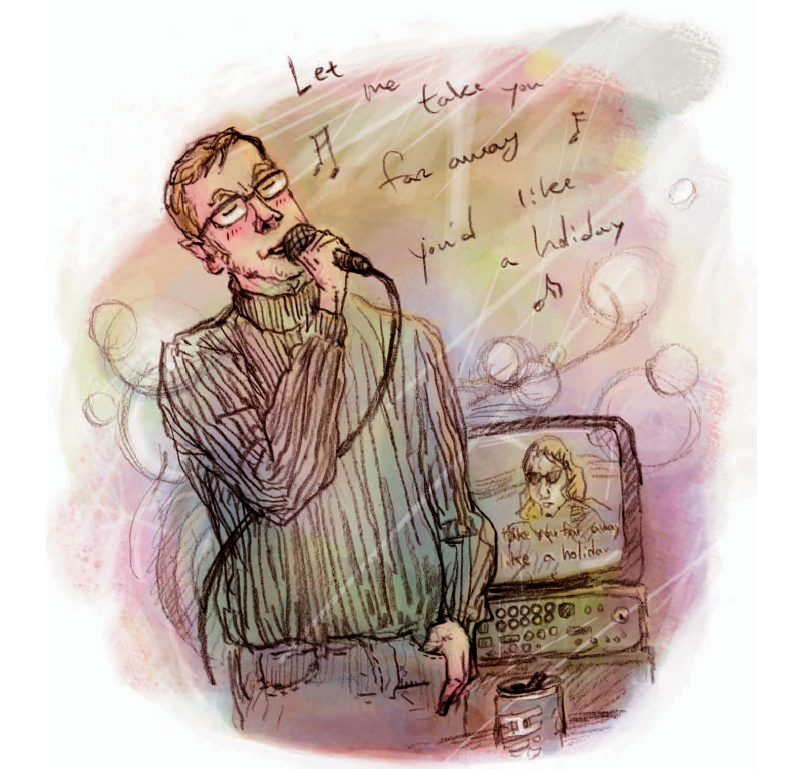

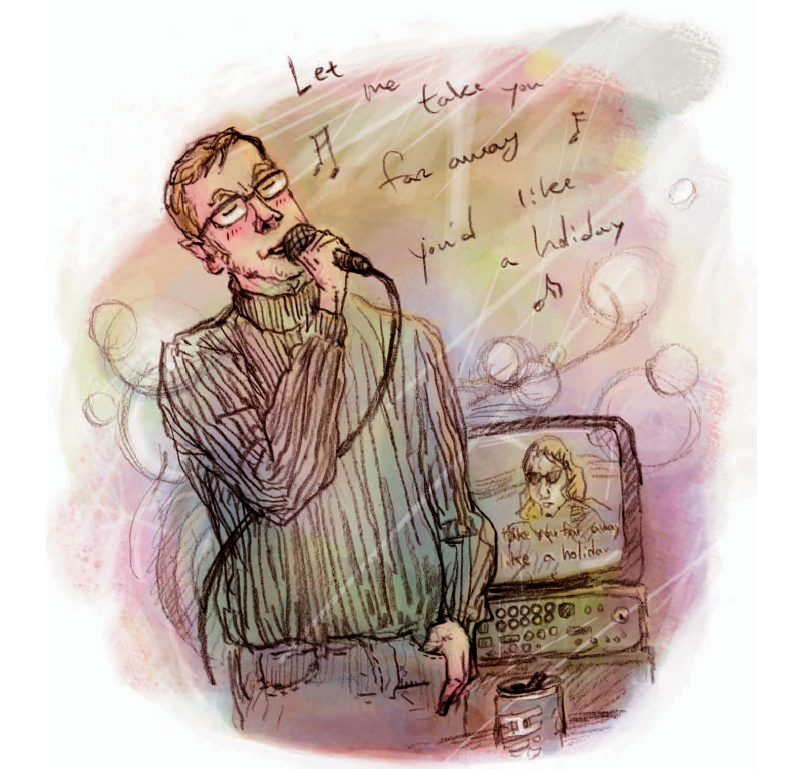

My first time, as such things tend to be, was unforgettable. Though a lifelong lover of rock and pop music, and a passionate bathroom and mirror-front singer, I had never for a second countenanced going out with friends to a noraebang, much less singing at one. After much prompting, and emboldened by generous amounts of beer, I finally summoned the courage to unleash my debut song — Abba’s “Dancing Queen,” if memory serves — on an expectant public.

Gradually shedding my stiff British reserve, my voice grew from a timid crackle to a triumphal bellow, drawing whoops of approval from my companions. It was nothing short of liberating. Having been thus blooded in noraebang, I was at something of an advantage when the noraebang call inevitably came in Korea. In my earliest visits there, I could see much of what I recalled from my previous noraebang experiences: the disco lights, cavern-esque rooms and tinny musical accompaniments were all present and correct.

Yet things were a bit different here, too. For one thing, the song lists, while containing the usual English-language standards, also had strikingly outre inclusions (who could resist a sing-along to metal titans Helloween or Pantera?). For another, in a country not known for its abstemiousness, most noraebang were, and still are, completely dry (although, thankfully for my own singing career, some places do sell booze). And crucially, thanks to the relative ease of learning the Korean alphabet, hangeul, I was able from a very early stage to sing a song or two in Korean, which, for an audience unaccustomed to hearing a foreigner speak Korean, never mind sing it, was often met with something approaching hysteria.

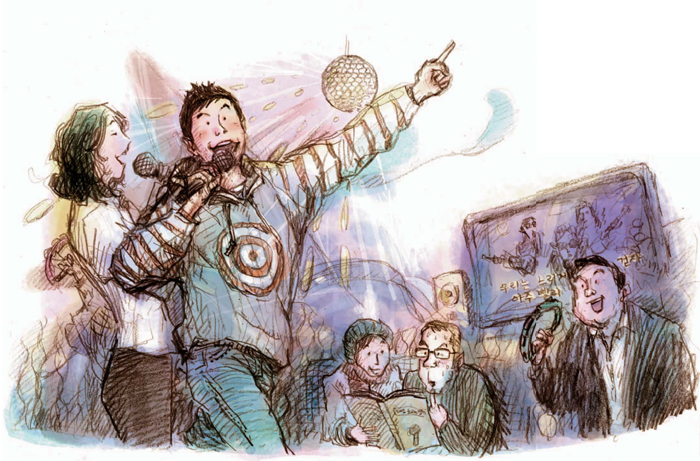

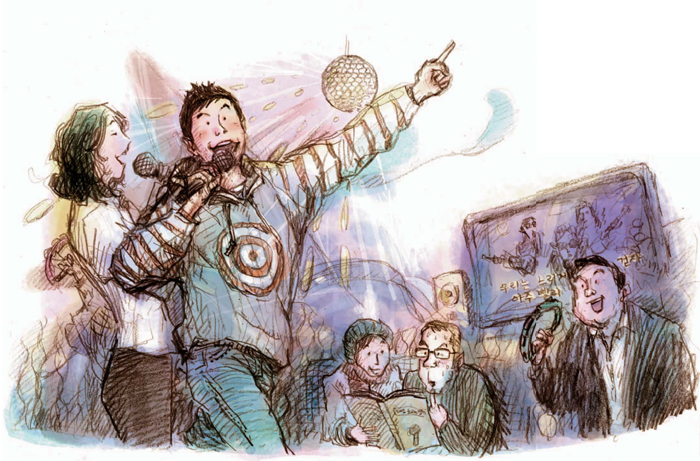

Subsequent noraebang visits with local friends yielded glimpses of Korea that no guidebook, and certainly no visit to the usual tourist sights, could ever provide. For me, this was especially the case after I took up a job in a big publishing firm, where all the other staff were Korean. Every few weeks our department or, on bigger occasions, the entire office would troop off for the infamous hoesik, or after-work food and drinks, gorge on barbecued pork and soju (the local grog) and then, with thudding certainty, make our way to the nearest noraebang. The change in these people I worked with was often extraordinary.

On coming into contact with a mic, a squelchy soundtrack and a backing video depicting unfeasibly happy people bounding through a Swiss hamlet, the sternest of clients and middle-aged office managers would transform into louche rockers or heartfelt crooners. The daintiest, most introverted young women would open their mouths to reveal lungs of fire. And while the famous Korean office hierarchy persisted even in these unceremonious surroundings — the most junior staff would sing first, drinking etiquette was scrupulously maintained and no one left until the boss did — there was, at least through the mist of several shots of whiskey too many, an undeniable sense of camaraderie, a feeling that tonight, at least, everyone was as one in the crucible of behaving very foolishly indeed.

On the times I subsequently went in groups including newly arrived foreign friends, though, I was newly reminded of just how alien karaoke was to many of them. Some would refuse outright to sing, while others would flick endlessly through the pages of the song catalog, never quite finding the right one.

Still others would choose a song, raise the mic to their mouths, then freeze and shrink back into their chairs. Having never experienced the joys of karaoke at home, these greenhorns were consumed with the kind of deep-rooted dread that only singing in front of their peers could inspire: A fear that their voice would be so bad, it would make a gaggle of alley cats sound like a barbershop quartet.

As I had once done, though, the karaoke refuseniks were rather missing the point. As I’ve discovered through my many visits, there can be few places anywhere where notions of making a fool of yourself are not so much disregarded as simply irrelevant. While a few of my Korean noraebang companions have been accomplished singers who clearly put in a bit of practice, the overwhelming majority were unashamedly poor, murdering everything from K-pop songs to old, maudlin Korean ballads to Gloria Gaynor with the same relentless vigor and effort.

But just by taking to the floor, and warbling along as best they could, they invariably prompted claps, cheers and equally woeful dancing among the onlooking crowd. In just this way, I have had some of my most hilarious nights out in Korea (the best ones, admittedly, helped along with a drink or six).

I’ve done P-Diddy in my native Scottish accent. I’ve sung late-night Scorpions duets with old friends. I’ve pogoed to A-ha’s “Take On Me.” And, most stirringly of all, I’ve stolen the show with stuttering renditions of Korean pop songs. Just as my friends back home would find moments of genuine poignancy by getting sloshed on beer, putting their arms around each other’s shoulders and howling along to the jukebox, Koreans, it has always seemed to me, find a real sense of togetherness in their song-room serenades. And as mystifying as karaokes may be for the uninitiated, the friendships formed over drunken, cacophonous noraebang nights may just be the ones that stay with you the longest.

The series of columns written by expats is about their experiences in Korea and has been made possible with the cooperation with Korea Magazine.

True enough, noraebang (literally “song room”) as it is known here, is one of those oddities, but it is far from unique to Korea. My earliest brush with it actually took place in Hong Kong, where I lived and worked for three years in the mid-’90s.

My first time, as such things tend to be, was unforgettable. Though a lifelong lover of rock and pop music, and a passionate bathroom and mirror-front singer, I had never for a second countenanced going out with friends to a noraebang, much less singing at one. After much prompting, and emboldened by generous amounts of beer, I finally summoned the courage to unleash my debut song — Abba’s “Dancing Queen,” if memory serves — on an expectant public.

Gradually shedding my stiff British reserve, my voice grew from a timid crackle to a triumphal bellow, drawing whoops of approval from my companions. It was nothing short of liberating. Having been thus blooded in noraebang, I was at something of an advantage when the noraebang call inevitably came in Korea. In my earliest visits there, I could see much of what I recalled from my previous noraebang experiences: the disco lights, cavern-esque rooms and tinny musical accompaniments were all present and correct.

Yet things were a bit different here, too. For one thing, the song lists, while containing the usual English-language standards, also had strikingly outre inclusions (who could resist a sing-along to metal titans Helloween or Pantera?). For another, in a country not known for its abstemiousness, most noraebang were, and still are, completely dry (although, thankfully for my own singing career, some places do sell booze). And crucially, thanks to the relative ease of learning the Korean alphabet, hangeul, I was able from a very early stage to sing a song or two in Korean, which, for an audience unaccustomed to hearing a foreigner speak Korean, never mind sing it, was often met with something approaching hysteria.

Subsequent noraebang visits with local friends yielded glimpses of Korea that no guidebook, and certainly no visit to the usual tourist sights, could ever provide. For me, this was especially the case after I took up a job in a big publishing firm, where all the other staff were Korean. Every few weeks our department or, on bigger occasions, the entire office would troop off for the infamous hoesik, or after-work food and drinks, gorge on barbecued pork and soju (the local grog) and then, with thudding certainty, make our way to the nearest noraebang. The change in these people I worked with was often extraordinary.

On coming into contact with a mic, a squelchy soundtrack and a backing video depicting unfeasibly happy people bounding through a Swiss hamlet, the sternest of clients and middle-aged office managers would transform into louche rockers or heartfelt crooners. The daintiest, most introverted young women would open their mouths to reveal lungs of fire. And while the famous Korean office hierarchy persisted even in these unceremonious surroundings — the most junior staff would sing first, drinking etiquette was scrupulously maintained and no one left until the boss did — there was, at least through the mist of several shots of whiskey too many, an undeniable sense of camaraderie, a feeling that tonight, at least, everyone was as one in the crucible of behaving very foolishly indeed.

On the times I subsequently went in groups including newly arrived foreign friends, though, I was newly reminded of just how alien karaoke was to many of them. Some would refuse outright to sing, while others would flick endlessly through the pages of the song catalog, never quite finding the right one.

Still others would choose a song, raise the mic to their mouths, then freeze and shrink back into their chairs. Having never experienced the joys of karaoke at home, these greenhorns were consumed with the kind of deep-rooted dread that only singing in front of their peers could inspire: A fear that their voice would be so bad, it would make a gaggle of alley cats sound like a barbershop quartet.

As I had once done, though, the karaoke refuseniks were rather missing the point. As I’ve discovered through my many visits, there can be few places anywhere where notions of making a fool of yourself are not so much disregarded as simply irrelevant. While a few of my Korean noraebang companions have been accomplished singers who clearly put in a bit of practice, the overwhelming majority were unashamedly poor, murdering everything from K-pop songs to old, maudlin Korean ballads to Gloria Gaynor with the same relentless vigor and effort.

But just by taking to the floor, and warbling along as best they could, they invariably prompted claps, cheers and equally woeful dancing among the onlooking crowd. In just this way, I have had some of my most hilarious nights out in Korea (the best ones, admittedly, helped along with a drink or six).

I’ve done P-Diddy in my native Scottish accent. I’ve sung late-night Scorpions duets with old friends. I’ve pogoed to A-ha’s “Take On Me.” And, most stirringly of all, I’ve stolen the show with stuttering renditions of Korean pop songs. Just as my friends back home would find moments of genuine poignancy by getting sloshed on beer, putting their arms around each other’s shoulders and howling along to the jukebox, Koreans, it has always seemed to me, find a real sense of togetherness in their song-room serenades. And as mystifying as karaokes may be for the uninitiated, the friendships formed over drunken, cacophonous noraebang nights may just be the ones that stay with you the longest.

The series of columns written by expats is about their experiences in Korea and has been made possible with the cooperation with Korea Magazine.