View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

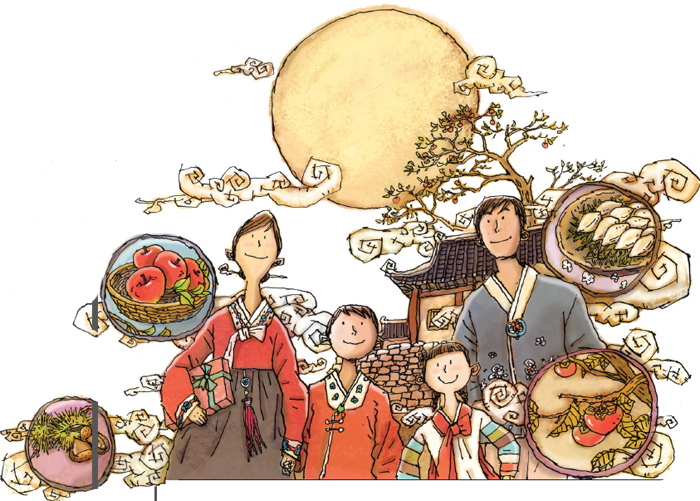

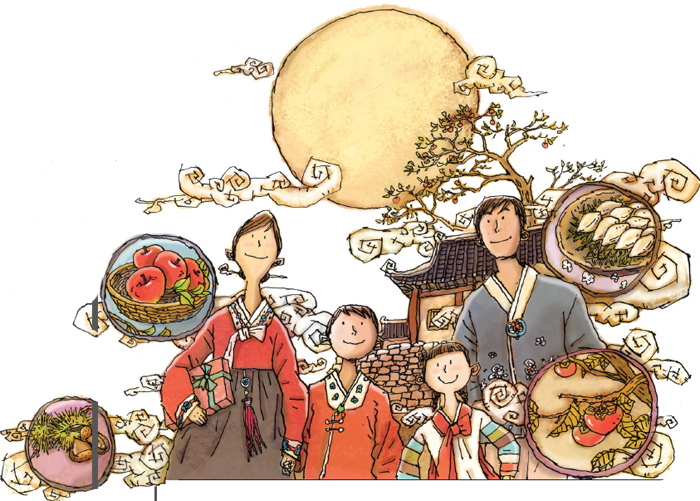

Besides the gorgeous fall weather, the arrival of September 22 (15th day of August of the lunar calendar) in Korea also mean only one thing: chuseok, the “Korean Thanksgiving.” In a country where so much tradition has been lost, chuseok offers an intimate reacquaintance with the ways of old, and rituals that solidified one expat’s affection for his new home.

To me, few sights in this world are as stunning as a persimmon tree against a brilliant blue autumn sky, its branches sagging under the weight of swollen orange fruit. This is a common sight across the Korean countryside, but one that I never tire of seeing. By tradition, when the fruit is plucked from the boughs a few persimmons are left behind for the magpies, heralded in Korean folklore as the bearers of good news. This act typifies Koreans’ connection to nature, the harvest, and their agrarian roots. Those who have visited Seoul, with its bustling streets, endless crowds of people, skyscrapers, and bright lights might laugh, but I would argue that Korea is still largely rooted in its agrarian past and the countryside.

Korean society and culture continues to revolve around the consumption of food and drink, and emphasis is always placed on using the freshest and healthiest ingredients. It goes without saying that to a people so deeply intertwined with their agrarian past, celebrating the harvest would be of the utmost importance. Chuseok, sometimes referred to as hangawi, is a Korean harvest festival that lasts for three days around the Autumn equinox. Every chuseok, the crowded metropolis of Seoul becomes a ghost town as people leave en masse for their ancestral hometowns in the countryside. Buses and trains are sold out months in advance, and even the relatively low demand for domestic air travel skyrockets. Cars pack the highways and slowly snake, bumper-to-bumper, out of Seoul and to every remote location throughout the peninsula. Drive times quadruple and hawkers freely walk between traffic lanes selling their wares to Korean wayfarers engaged in this yearly exodus.

The final destination on this journey is the keun-jip, literally translated as “big house,” but referring to the residence of the oldest living male family member. All immediate family members gather at the keun-jip to celebrate the harvest and to pay thanks to their ancestors by preparing and sharing a great feast.

Foods traditionally eaten on this day tend to vary by household, but commonly one can find meats like bulgogi or galbi, two traditional meat dishes, japchae, a dish prepared with various vegetables, meats and cellophane noodles, jeon, a pancake like side dish prepared by pan fried vegetables, fish and meat, coated in a batter of flour and eggs, and of course a wide variety of fruits, nuts, and herbs. The food most commonly associated with chuseok, however, has to be songpyeon. This delicious dessert is made from tteok, or glutinous rice cake, filled with a sweet mixture of sesame seeds, honey, sweet red bean or chestnut paste placed in the middle as filling. The flattened rice is folded around the mixture making a halfmoon shape.

The cakes are then loaded on a bed of pine needles and steamed into a delicious treat. Traditionally songpyeon was exchanged between neighbors, reminiscent of the American tradition of exchanging sweets during the Christmas season. All of this food, however, serves a greater function than to just be eaten. Before anyone even touches the food, it is given as an offering to the ancestors in a ceremony called charye. The food and rice wine are arranged in an impressive display on a table in front of the ancestral burial mounds or in the family’s home. The family gathers together in front of the table and recites prayers while offering the rice wine. Then, family members make full bows, prostrating on the floor, offering thanks for the blessings received and memorializing their deceased family members.

The cakes are then loaded on a bed of pine needles and steamed into a delicious treat. Traditionally songpyeon was exchanged between neighbors, reminiscent of the American tradition of exchanging sweets during the Christmas season. All of this food, however, serves a greater function than to just be eaten. Before anyone even touches the food, it is given as an offering to the ancestors in a ceremony called charye. The food and rice wine are arranged in an impressive display on a table in front of the ancestral burial mounds or in the family’s home. The family gathers together in front of the table and recites prayers while offering the rice wine. Then, family members make full bows, prostrating on the floor, offering thanks for the blessings received and memorializing their deceased family members.

After the ceremony is finished, the family sits down together and partakes of the bountiful feast. During this three-day reunion, cousins, uncles, aunts and grandparents spend a great deal of time together. Traditionally families took part in folk games like tug-of-war, archery, or ssireum, a form of traditional Korean wrestling. However, in more recent times, it’s much more likely that family members will share beers while munching on squid and peanuts, watch TV or play Go-Stop, a popular Korean card game played with hwatu cards.

FAMILY REUNION From start to finish, the holiday emphasizes the connection between people and their hometowns, families, ancestors and the Earth. Sin-to-bul-i, a common Korean idiom often used to say that the agricultural products of one’s hometown are the best, is literally translated as “the body and the earth cannot be separated.” This typifies Koreans’ attitudes when it comes to chuseok. Koreans’ respect for their traditions is only trumped by their passion and desire for sharing them with others.

During my seven years in Korea, I have had ample opportunities to participate in Korean traditions with my friends and acquaintances. I first encountered this hospitality as a young man living in the small town of Gunsan. One of my coworkers, Mr. Yu, was so concerned that I would be lonely or go hungry during the extended holiday when shops close that he invited me to spend the holiday with him and his family. While never having experienced chuseok, nor understanding fully what it would mean to a Korean to be alone on such an important day, I was touched by his concern. On the first morning we rose early, packed our lunches, and headed to the mountains to trim the grass around his family’s tombs. With four generations of the Yu family sprawled on the side of the mountains, by grass-covered mounds and stone pillars, there was a lot of ground to cover. Armed with weed eaters, each of us took painstaking care to trim the grass to a uniform level in the brisk autumn air. Coming from a land where we pay cemeteries to look after the remains of our loved ones, this somehow felt more intimate.

When we were finished and the sun began cresting on the ridge of the mountain adjacent, we sat down beside the graves and ate our lunch, while taking in the fall landscape. Mr. Yu took great pride in telling me the history of his ancestors and explaining the auspicious location where their burial mounds were placed. He said that the location, flanked on either side by a mountain and overlooking a small stream, was built under the optimum conditions in feng shui (pungsu in Korean). He informed me that as a result of this auspicious positioning, the spirits of his ancestors were resting in peace and could pass on more blessings to his family.

The next day, when we visited with his family in tow, I watched as his wife took care to set up a small wooden table at the base of the mountain where she arranged the food. This was followed by a few recited prayers to the ancestors, the pouring out of a few shots of a rice wine that smelled heavily of herbs, the cutting and offering of fruit, bowing, and a few informal words imparted from a father to his children about the importance of family.

After the ancestral rite finished, we gathered together on a shiny silver mat and began to eat and talk and laugh with one another. As I gripped a fried pepper between my chopsticks and began raising it to my mouth, it occurred to me that I was seated there with six generations of this family. This was a family reunion that spanned hundreds of years. Never in a million years before I came to Korea could I have imagined such a gathering.

As we were preparing to leave, I saw the brilliant orange of the persimmons with the wide blue fall sky behind it stretching into eternity for the first time in my life. Mr. Yu, sensing my gaze, began reciting a poem entitled, “Persimmon Tree, Food for Magpies.” The poem is a tale of the ripe sweet fruit growing on the branches of a persimmon tree. It goes on to describe how the tree offers this fruit as food for the magpie to share with his family as they prepare for the winter, and how the branches, recently lightened of their fruit, reach into the sky.

He went on to relate the tradition of leaving a few persimmons on the tree and it was then that I first realized that Korea is about connections. Connections to others. Connections to the past. Connections to the earth. Thanks to the experience of that chuseok and all the others that followed, when I was invited to participate with friends’ families or brought left-over food, I now understand this and feel connected as well. In a sense I am the magpie and Korea has been my persimmon tree.

By Joel Browning | Illustrations by Jo Seung-hyeon | photograph by Kim Nam-heon

*The series of columns written by expats is about their experiences in Korea and has been made possible with the cooperation with Korea Magazine.

To me, few sights in this world are as stunning as a persimmon tree against a brilliant blue autumn sky, its branches sagging under the weight of swollen orange fruit. This is a common sight across the Korean countryside, but one that I never tire of seeing. By tradition, when the fruit is plucked from the boughs a few persimmons are left behind for the magpies, heralded in Korean folklore as the bearers of good news. This act typifies Koreans’ connection to nature, the harvest, and their agrarian roots. Those who have visited Seoul, with its bustling streets, endless crowds of people, skyscrapers, and bright lights might laugh, but I would argue that Korea is still largely rooted in its agrarian past and the countryside.

Korean society and culture continues to revolve around the consumption of food and drink, and emphasis is always placed on using the freshest and healthiest ingredients. It goes without saying that to a people so deeply intertwined with their agrarian past, celebrating the harvest would be of the utmost importance. Chuseok, sometimes referred to as hangawi, is a Korean harvest festival that lasts for three days around the Autumn equinox. Every chuseok, the crowded metropolis of Seoul becomes a ghost town as people leave en masse for their ancestral hometowns in the countryside. Buses and trains are sold out months in advance, and even the relatively low demand for domestic air travel skyrockets. Cars pack the highways and slowly snake, bumper-to-bumper, out of Seoul and to every remote location throughout the peninsula. Drive times quadruple and hawkers freely walk between traffic lanes selling their wares to Korean wayfarers engaged in this yearly exodus.

The final destination on this journey is the keun-jip, literally translated as “big house,” but referring to the residence of the oldest living male family member. All immediate family members gather at the keun-jip to celebrate the harvest and to pay thanks to their ancestors by preparing and sharing a great feast.

Foods traditionally eaten on this day tend to vary by household, but commonly one can find meats like bulgogi or galbi, two traditional meat dishes, japchae, a dish prepared with various vegetables, meats and cellophane noodles, jeon, a pancake like side dish prepared by pan fried vegetables, fish and meat, coated in a batter of flour and eggs, and of course a wide variety of fruits, nuts, and herbs. The food most commonly associated with chuseok, however, has to be songpyeon. This delicious dessert is made from tteok, or glutinous rice cake, filled with a sweet mixture of sesame seeds, honey, sweet red bean or chestnut paste placed in the middle as filling. The flattened rice is folded around the mixture making a halfmoon shape.

After the ceremony is finished, the family sits down together and partakes of the bountiful feast. During this three-day reunion, cousins, uncles, aunts and grandparents spend a great deal of time together. Traditionally families took part in folk games like tug-of-war, archery, or ssireum, a form of traditional Korean wrestling. However, in more recent times, it’s much more likely that family members will share beers while munching on squid and peanuts, watch TV or play Go-Stop, a popular Korean card game played with hwatu cards.

FAMILY REUNION From start to finish, the holiday emphasizes the connection between people and their hometowns, families, ancestors and the Earth. Sin-to-bul-i, a common Korean idiom often used to say that the agricultural products of one’s hometown are the best, is literally translated as “the body and the earth cannot be separated.” This typifies Koreans’ attitudes when it comes to chuseok. Koreans’ respect for their traditions is only trumped by their passion and desire for sharing them with others.

During my seven years in Korea, I have had ample opportunities to participate in Korean traditions with my friends and acquaintances. I first encountered this hospitality as a young man living in the small town of Gunsan. One of my coworkers, Mr. Yu, was so concerned that I would be lonely or go hungry during the extended holiday when shops close that he invited me to spend the holiday with him and his family. While never having experienced chuseok, nor understanding fully what it would mean to a Korean to be alone on such an important day, I was touched by his concern. On the first morning we rose early, packed our lunches, and headed to the mountains to trim the grass around his family’s tombs. With four generations of the Yu family sprawled on the side of the mountains, by grass-covered mounds and stone pillars, there was a lot of ground to cover. Armed with weed eaters, each of us took painstaking care to trim the grass to a uniform level in the brisk autumn air. Coming from a land where we pay cemeteries to look after the remains of our loved ones, this somehow felt more intimate.

When we were finished and the sun began cresting on the ridge of the mountain adjacent, we sat down beside the graves and ate our lunch, while taking in the fall landscape. Mr. Yu took great pride in telling me the history of his ancestors and explaining the auspicious location where their burial mounds were placed. He said that the location, flanked on either side by a mountain and overlooking a small stream, was built under the optimum conditions in feng shui (pungsu in Korean). He informed me that as a result of this auspicious positioning, the spirits of his ancestors were resting in peace and could pass on more blessings to his family.

The next day, when we visited with his family in tow, I watched as his wife took care to set up a small wooden table at the base of the mountain where she arranged the food. This was followed by a few recited prayers to the ancestors, the pouring out of a few shots of a rice wine that smelled heavily of herbs, the cutting and offering of fruit, bowing, and a few informal words imparted from a father to his children about the importance of family.

After the ancestral rite finished, we gathered together on a shiny silver mat and began to eat and talk and laugh with one another. As I gripped a fried pepper between my chopsticks and began raising it to my mouth, it occurred to me that I was seated there with six generations of this family. This was a family reunion that spanned hundreds of years. Never in a million years before I came to Korea could I have imagined such a gathering.

As we were preparing to leave, I saw the brilliant orange of the persimmons with the wide blue fall sky behind it stretching into eternity for the first time in my life. Mr. Yu, sensing my gaze, began reciting a poem entitled, “Persimmon Tree, Food for Magpies.” The poem is a tale of the ripe sweet fruit growing on the branches of a persimmon tree. It goes on to describe how the tree offers this fruit as food for the magpie to share with his family as they prepare for the winter, and how the branches, recently lightened of their fruit, reach into the sky.

He went on to relate the tradition of leaving a few persimmons on the tree and it was then that I first realized that Korea is about connections. Connections to others. Connections to the past. Connections to the earth. Thanks to the experience of that chuseok and all the others that followed, when I was invited to participate with friends’ families or brought left-over food, I now understand this and feel connected as well. In a sense I am the magpie and Korea has been my persimmon tree.

By Joel Browning | Illustrations by Jo Seung-hyeon | photograph by Kim Nam-heon

*The series of columns written by expats is about their experiences in Korea and has been made possible with the cooperation with Korea Magazine.