View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

Golden lacquer, hwangchil in Korean, is

paint from a natural source with a mysterious

golden hue. It has been used since the

Baekje Kingdom (18 B.C.–A.D. 660). The

skills to make the lacquer and apply it to

craftwork have long been forgotten. Mr.

Koo Young-kook is one of a few masters

who are reviving these skills and bringing

the lacquer back into daily life. Koo’s studio

is filled with shimmering golden jars, cups

and other works of art.

HANDICRAFT WITH PRECIOUS MATERIAL

“I visited the School of Engineering at Kyushu University in Japan in 1990. I was astonished at the thorough research on hwangchil that had been done by a Japanese professor. Hwangchil was a unique traditional handicraft of Korea, and the Japanese professor had researched it more deeply than anyone in Korea.” At that time, Koo had been making lacquer handicraft and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl since graduating from high school in 1978, but he decided at that moment in 1990 to begin exploring it much more extensively. Golden lacquer has an impressive elegance, is remarkably resistant to heat and water and is very durable. This is why it was widely used in ancient times to decorate the surfaces of craftworks. The oldest known record of it is in the “History of the Three Kingdoms” (1145) or Samguksagi in Korean. Baekje was one of three kingdoms on the Korean Peninsula at the time, and the Samguksagi states that Baekje sent armor bearing the golden lacquer as tribute to the king of Goguryeo (37 B.C.–A.D. 668).

Golden lacquer is made from the sap of the hwangchil tree (Dendropanax morbifera Lev.). The sap is milky-white upon extraction and gradually turns yellowish-amber in color when exposed to air. The sap has long been considered precious because it can only be extracted from a tree that is at least 15 years old and one tree can yield only 8.6 at a time, just enough to fill a small cup. Then, the sap must be refined. This species of tree nearly went extinct during the Joseon period (1392–1910) as it was over-exploited to meet the demand for tribute offerings to China during the Ming and Qing dynasties, as well as to the king and the royal family of Joseon. After the Second Manchu Invasion (1636-1639), the use of the lacquer was banned, even by the royal family. It was only allowed for emperors in the Forbidden City, the imperial palace of Ming and Qing dynasties in Beijing.

“The best aspect of hwangchil is its

golden color with an elegantly subdued

glow. Its golden hue has a noble and elegant

shimmer, unlike the glittering glare of

metals. That is why it has been treasured. It

even has a delicate scent of wood,” says

Koo.

“The best aspect of hwangchil is its

golden color with an elegantly subdued

glow. Its golden hue has a noble and elegant

shimmer, unlike the glittering glare of

metals. That is why it has been treasured. It

even has a delicate scent of wood,” says

Koo.

When the native hwangchil tree nearly went extinct, the craft of lacquerwork almost disappeared. After nearly 200 years, the traditional craft has been recently revived thanks to the discovery of several wild hwangchil trees. The Natural habitat of the tree is along the southeastern coast of the Korea Peninsula and on Jeju Island.

“Lacquer is said to last 1,000 years, but hwangchil lasts 10,000 years. It is regrettable that such a sophisticated craft had nearly fallen into total oblivion while lacquer painting was still so widely recognized. During the Japanese occupation (1910- 1945), any Korean who even tried to pull the leaves off of a hwangchil tree was arrested. I suspect that the artistry would have been taken to Japan at that time,” added the master.

BRINING HWANGCHIL INTO DAILY LIFE

Koo has been working hard to create works decorated with the golden lacquer for several decades. He even earned a doctorate in it for extensive research and experimentation. His efforts to resurrect the skill of making and painting with lacquer have been recognized by international art lovers. Golden-lacquered artworks have been displayed at various international exhibitions and are found in the first lady’s reception room at Cheong Wa Dae. Koo is endeavoring to bring hwangchil closer to the public by applying it to items such as dishware and even golf putters.

“Crafts are not just for display and appreciation. They are for daily use. Works of art that can be part of our daily lives can be loved and appreciated for a long time.”

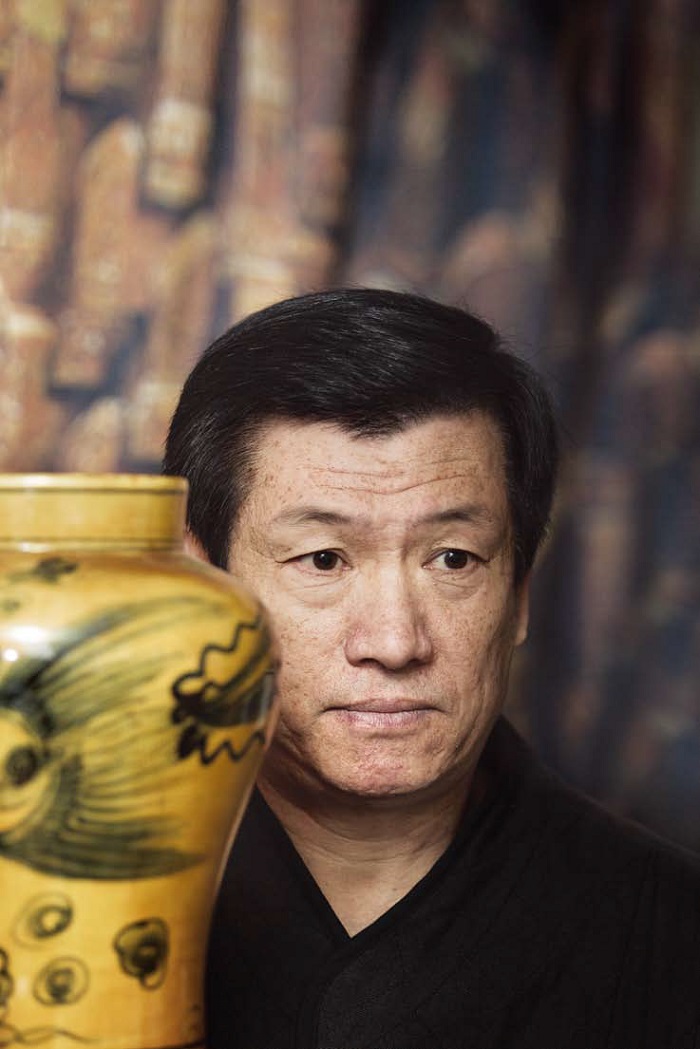

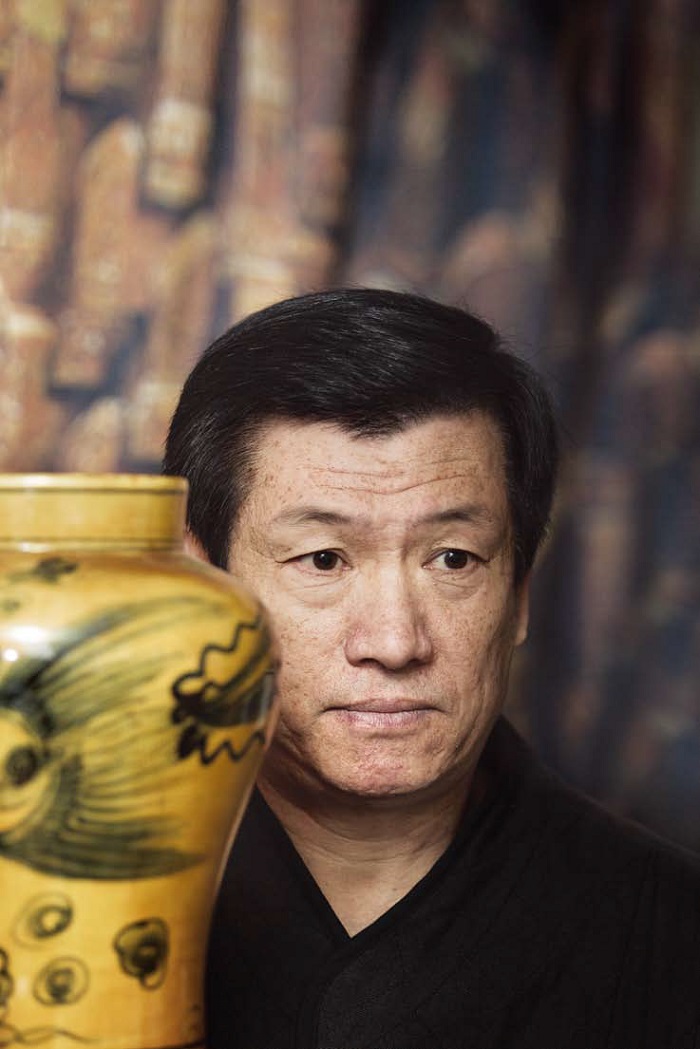

Master Koo Young-kook.

HANDICRAFT WITH PRECIOUS MATERIAL

“I visited the School of Engineering at Kyushu University in Japan in 1990. I was astonished at the thorough research on hwangchil that had been done by a Japanese professor. Hwangchil was a unique traditional handicraft of Korea, and the Japanese professor had researched it more deeply than anyone in Korea.” At that time, Koo had been making lacquer handicraft and lacquerware inlaid with mother-of-pearl since graduating from high school in 1978, but he decided at that moment in 1990 to begin exploring it much more extensively. Golden lacquer has an impressive elegance, is remarkably resistant to heat and water and is very durable. This is why it was widely used in ancient times to decorate the surfaces of craftworks. The oldest known record of it is in the “History of the Three Kingdoms” (1145) or Samguksagi in Korean. Baekje was one of three kingdoms on the Korean Peninsula at the time, and the Samguksagi states that Baekje sent armor bearing the golden lacquer as tribute to the king of Goguryeo (37 B.C.–A.D. 668).

Golden lacquer is made from the sap of the hwangchil tree (Dendropanax morbifera Lev.). The sap is milky-white upon extraction and gradually turns yellowish-amber in color when exposed to air. The sap has long been considered precious because it can only be extracted from a tree that is at least 15 years old and one tree can yield only 8.6 at a time, just enough to fill a small cup. Then, the sap must be refined. This species of tree nearly went extinct during the Joseon period (1392–1910) as it was over-exploited to meet the demand for tribute offerings to China during the Ming and Qing dynasties, as well as to the king and the royal family of Joseon. After the Second Manchu Invasion (1636-1639), the use of the lacquer was banned, even by the royal family. It was only allowed for emperors in the Forbidden City, the imperial palace of Ming and Qing dynasties in Beijing.

Koo Young-kook has dedicated himself to making

When the native hwangchil tree nearly went extinct, the craft of lacquerwork almost disappeared. After nearly 200 years, the traditional craft has been recently revived thanks to the discovery of several wild hwangchil trees. The Natural habitat of the tree is along the southeastern coast of the Korea Peninsula and on Jeju Island.

“Lacquer is said to last 1,000 years, but hwangchil lasts 10,000 years. It is regrettable that such a sophisticated craft had nearly fallen into total oblivion while lacquer painting was still so widely recognized. During the Japanese occupation (1910- 1945), any Korean who even tried to pull the leaves off of a hwangchil tree was arrested. I suspect that the artistry would have been taken to Japan at that time,” added the master.

BRINING HWANGCHIL INTO DAILY LIFE

Koo has been working hard to create works decorated with the golden lacquer for several decades. He even earned a doctorate in it for extensive research and experimentation. His efforts to resurrect the skill of making and painting with lacquer have been recognized by international art lovers. Golden-lacquered artworks have been displayed at various international exhibitions and are found in the first lady’s reception room at Cheong Wa Dae. Koo is endeavoring to bring hwangchil closer to the public by applying it to items such as dishware and even golf putters.

“Crafts are not just for display and appreciation. They are for daily use. Works of art that can be part of our daily lives can be loved and appreciated for a long time.”