Jina Nam is a researcher at the Cultural Heritage Restoration Foundation in Seoul. (Kang Sung-chul)

By Yoon Seungjin of Korea.net and Kang Sung-chul of Yonhap News

"Cultural property isn't just legacy from the past. It's a mirror reflecting the past, present and future of humanity, so returning it to its original country if it's been looted is natural."

In an interview with Korea.net and Yonhap News on Nov. 17, Jina Nam, 29, a researcher at the Seoul-based Cultural Heritage Restoration Foundation, said, "The return of looted cultural property is a symbol of reconciliation and cooperation between parties not only in the past but also the present."

Nam grew up in Poland as a second-generation Korean expat as the daughter of Nam Jong-seok, president of the Federation of Korean Associations in Poland.

Despite living in a faraway land, she studied both the Korean language and history thanks to his father, who emphasized the importance of ethnic roots and identity. Thus her interest in her cultural heritage grew naturally.

Thanks to a scholarship from the Overseas Korean Foundation to study in the motherland, Nam studied psychology at Seoul National University and earned a master's in international cooperation at Yonsei University.

Since 2020, she has worked as a researcher at the foundation, which also employs her father. She has taken part in the repatriation efforts of Korean cultural assets abroad including the Uam Song Si-yeol and ihakjongyo woodblocks and Munsin Gyeonghwi tombstone.

The English-language edition of her book "Cultural Artifact Repatriation: Symbolic Diplomacy" came out last year. The work proposes letting go of historical grievances to build a foundation for equal future relations between a country that stole a cultural property and the item's nation of origin.

In May this year, Nam took the lead in conducting a comprehensive survey of Korean cultural assets in three Eastern European countries: Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic.

The following are excerpts from the interview.

Researcher Jina Nam (second from left) on May 10 checks Korean cultural heritage with officials at the National Museum in Krakow, Poland. (Jina Nam)

How did you maintain a sense of Korean identity while living abroad?

Since I was a kid, my parents have always emphasized to have a sense of Korean identity regardless of where I live. They taught me how to use chopsticks and made me eat kimchi. Also, I naturally learned more about Korea while preparing a presentation for the event "United Nations Day" at a nearby international school. I also watched a lot of historical K-dramas. Constantly watching series like "Emperor of the Sea" and "Dae Jo-yeong" fostered my interest in Korean history.

What image does the Polish public have of Korea?

Korea had a positive reputation in Poland when I was growing up there in the 1990s. It experienced an economic downturn right after independence from the former Soviet Union but brisk investment by Korean companies offered some breathing room. Plus, the 2002 Korea-Japan World Cup and Hallyu (Korean wave) contributed to the forming of a positive image of Korea. Above all, many Polish citizens were surprised by the exemplary response and quarantine activities of the Korean people during the coronavirus outbreak, which further raised the status of Koreans.

What are the differences in how Koreans and Poles perceive cultural heritage?

Korea still strongly tends to think of the preservation and development of cultural assets as an industrial sector. Unlike Poland, which recognizes such assets as valuable heritage and strives to preserve them, Korea is also apparently more focused on utilizing such assets for tourism and business. Of course, given Korea's recent rise as a cultural power, the nation has begun to value the influence of cultural assets. For example, I see greater efforts to restore and preserve cultural assets like the restoration of Gyeongbokgung Palace's woldae (elevated royal stage), which was destroyed during Japanese colonial rule.

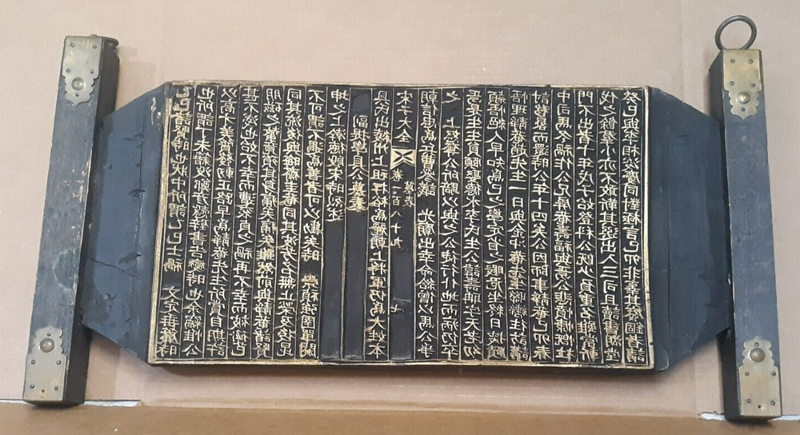

The woodblock print Songja Daejeon by Uam Song Si-yeol of the Joseon Dynasty was returned to Korea in September last year by the U.S. through the efforts of the Cultural Heritage Restoration Foundation. (Jina Nam)

What meaning does the return of looted cultural property hold?

The meaning of returning cultural property can be summarized in four words: reconciliation, cooperation, conflict and justice. Sometimes two countries reconcile and cooperate through talks on return and other times get embroiled in disputes during the process. Just can also be served through the recovery of looted cultural properties. As an intersection of diverse interests, such returns can be a clue to resolving human conflict in times of civilizational transition such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

What was the main takeaway from the survey of Korean cultural assets in three Eastern European countries?

Most of the museums in the three countries that conducted the research and survey actively cooperated. They needed our foundation's help because of the difficultly in determining the origins of Asian artifacts in their collections. This is due to European museums having many curators from China or Japan but few from Korea. When I did my own research, I found that many cultural heritage items from Asia were categorized as Korean.

Researcher Jina Nam (center) on Sept. 5 appraises cultural assets at an exhibition of reclaimed cultural heritage at Leesu Gallery in Los Angeles' Koreatown. (Jina Nam)

How can Korea help global efforts to repatriate cultural assets?

Korea has risen from one of the poorest countries on Earth to a developed one in the fastest time in global history. It's also a cultural power thanks to its influential soft power as shown by diverse Korean content including K-pop. Through this, Korea as a cultural power can play a pivotal role in the repatriation of cultural property. Positioned to extend assistance to countries through its own history as a victim of cultural plunder, the nation can become a global leader in this crucial field.

What cultural properties from other countries has Korea not yet returned?

Just a few confirmed cases remain but the lack of clear origin labeling poses a challenge in assessing the situation. Most museums in Korea do not properly label the origins of their artifacts, hindering the identification of the sources of cultural properties. In certain instances, even artifacts returned from abroad lack clear labeling of their origins.

Given the global movement toward enhancing transparency in the origins of cultural assets, we must swiftly implement a system for this issue. Unlike other countries, Korea has a centralized museum in the capital housing many of the country's cultural assets but the majority of them lack proper labeling of their origins. So we need efforts to identify their origins and return them to their proper homes.

scf2979@korea.kr