Lee Na-Young, chair of the board of the Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, on July 24 takes a photo in front of a drawing by victim Kang Duk-kyung.

By Lee Jihae

Photos = Lee Jihae

Aug. 14 is International Memorial Day for Japanese Military Comfort Women. The occasion marks when Kim Hak-soon on Aug. 14, 1991, became the first "comfort woman," a euphemism used by the Japanese military in the early 20th century to refer to its sex slaves, to testify on her ordeal.

To mark her historic testimony, preserve the historical context, and restore the dignity and honor of the victims, the Korean government in 2018 designated this national commemorative day.

Korea.net on July 24 interviewed Lee Na-Young, a sociology professor at Chung-Ang University and head of the Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan. She said, "Memories survive when recorded and gain strength through solidarity."

The following are excerpts from the interview.

Use of the terms "comfort women" and "sex slaves" is debated. Which is correct?

The term "comfort women" reflects the perspective of the male perpetrators, erasing the coercion and violence involved. The United Nations (U.N.) officially calls it "military sexual slavery by Japan," but the victims are cautious of the term "sexual slavery" for causing great pain. We disagree with the historical term "comfort women" used by the Japanese military, but use it with single quotation marks to convey "so-called." The Korean government and our organization place "Japanese military" at the front to clearly identify the perpetrator.

In 2016, eight nations including Korea failed to register data on "comfort women" with UNESCO's Memory of the World Register. What happened?

On May 18, 2016, 14 civic organizations from eight countries -- Korea, Japan, China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor and the Netherlands -- held a signing ceremony for their joint application to register records on the Japanese military's "comfort women" in UNESCO's Memory of the World Register. The 2,744 records included victim testimonies, historical documents, activity records, photos and video as the largest application for such registration in history.

The right-wing faction of the Japanese government, however, sent a counter-application to oppose the records' registration. Tokyo, as the biggest contributor of dues to UNESCO at the time, also pressured UNESCO to block the bid by terminating its contribution funds. As a result, the civic organizations were barred from applying for the registration and UNESCO altered its regulations to require intergovernmental agreements to submit materials to the review committee. Thus registration was impossible if even a single nation opposed. This explains why records on the Japanese military's "comfort women" are still not on UNESCO's Memory of the World.

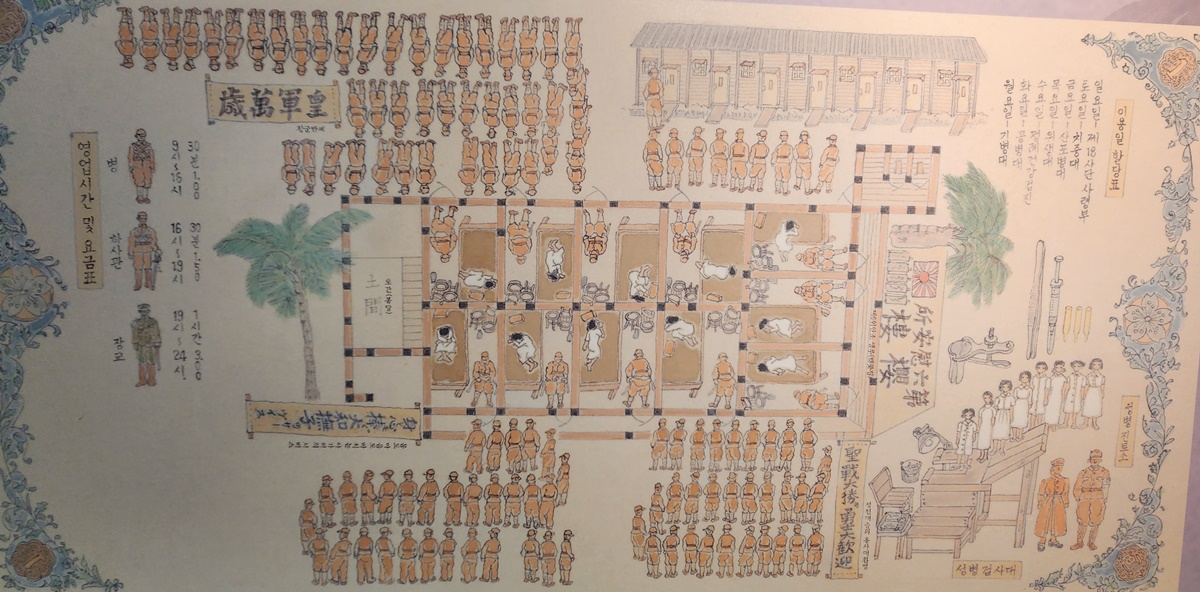

A drawing at the War and Women's Human Rights Museum in Seoul's Mapo-gu District shows sexual slavery victims at rooms in the center and Japanese soldiers waiting outside to rape them. Other troops line up in front of the rooms waiting for their turns. The lower right shows women lined up to be tested for sexually transmitted disease.

Why are the Kato (1992) and Kono (1993) statements from the Japanese government not accepted as sincere apologies on this matter?

With the spread of the women's rights movement in Korea, victims speaking out and the discovery of historical documents, the Japanese government found it impossible to keep denying history. So it issued the Kato Statement in 1992 in the name of Chief Cabinet Secretary Koichi Kato. It acknowledged for the first time the Japanese military's involvement in the matter and partially recognized the coercion used. The statement drew criticism, however, for omitting important details like truth finding and legal compensation.

The 1993 Kono Statement issued by Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono acknowledged that women were forcibly mobilized in the "recruitment" process and pledged history education on this. But the statement shifted the criminal responsibility to private companies and categorically denied illegality. Furthermore, the Japanese legislature never adopted the statement, so it cannot be accepted as a genuine apology. A more serious problem is Tokyo's continued attempts to debunk this statement through the distortion of history textbook content.

What are the problems of the bilateral agreement on the issue reached in 2015?

The agreement cannot be considered legitimate. Procedurally, there was no National Assembly report or public hearing, and the written accord had no signatures. It was also announced in the form of a joint news conference by the foreign ministers of both countries. And the news conference statement on the foreign ministry websites of the two countries slightly differs.

The terms of the agreement are also problematic. The Japanese government denied legal responsibility, claiming that the JPY 1 billion it gave wasn't "compensation" (reparation for illegal actions) but a "consolation payment." Also, it said the issue was "resolved finally and irreversibly" in trying to suppress further discussion. Tokyo even demanded the removal of "comfort women" statues, making the sincerity of its apology dubious.

The bigger problem is that the accord fails to reflect the voices of the victims, who had long yearned for the recovery of their human rights and honor. The U.N. also called this a "political agreement" that deviated from a victim-centered approach. The U.N. has consistently insisted that this isn't a genuine solution to the problem, and this explains why it keeps submitting recommendations and reports.

This statue of the Japanese military's "comfort women" is at the War and Women's Human Rights Museum in Seoul's Mapo-gu District.

What was the problem with Japan's 1995 launch of the Asian Women's Fund?

This wasn't official compensation from the Japanese government but a civic fundraising campaign. It was considered a Japanese government ploy to evade legal responsibility under the guise of "moral responsibility." This is why many victims opposed and rejected the money and the fund was eventually terminated in March 2007.

What must be done to resolve this long-standing issue?

Just six sexual slavery victims officially registered with the Korean government remain alive. Our duty is to record and preserve their memory even after they pass away. The Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan is working on a digital archive project. Our website digitizes victim testimonies and historical materials and offers service in Korean, English and Japanese.

We rent a floor of a villa as a storage space and run the War and Women's Human Rights Museum in Seoul's Mapo-gu District. We offer on-site lectures if 10 or more visitors apply through the museum's website. Our Butterfly Fund helps victims of wartime sexual violence around the world following the legacy of the "comfort women." Above all, public interest and participation are the most important factors in protecting the truth. Memory requires accountability and accountability requires action.

jihlee08@korea.kr