At about 40 percent of the way through the book, you begin to see Kim Joo-young's world. Born in 1939 in rural Gyeongsangbuk-do Province (North Gyeongsang Province), Kim Joo-young published "Stingray" ("홍어") in 1998 in the pages of Author's World (작가 세계). He says the book is to honor his mother. Perhaps it does, in a way. She certainly shows "toughness", and, indeed, that was probably the most-required personality trait to succeed in sexist, rural, superstitious, uneducated, poverty in the mountains of snowy Korea in the post-war wasteland. Good thing that the mother was "tough" and that she put food on the table during trying times, but that can also leave the children -- modern Korea's grandparents -- hollow or longing on the inside, and perhaps lacking in tenderness or sympathy.

The world Kim creates of early 1950s rural, mountainous, wintery Korea is one of fierce pride, bitter grudges, village in-fighting, family control, rumors upon rumors, and people who actually listen to rumors. Power, jealousy and anger are all there is. Seen from the 13-year-old boy Se-young's eyes -- presumably the author himself -- the adult world is one of suffering, keeping up with the Joneses and a farcical belief in "face" and "honor" to one's own detriment, as if what other people think is actually important. Caring is shown through beatings and chastisement, and the snows keep piling up outside, trapping our three main protagonists in a rural home, a rural village, a small village bar shining like a lit fish bowl, as cabin fever rises.

In this adult world of village in-fighting lives our narrator Se-young. It is his flights of fancy, his imagination, that give bits of color to the tale. He sees wings sprouting from his mother's back, a particularly touching scene. Lay that imagery down on Freud's couch and you can see that he does love his mother and that he sees that she has done much for him and for his future success. He makes friends with the neighbor's dog, a leaping galumphing beast that licks and laughs and barks. He tracks down the vagrant girl who becomes a quasi big sister. He is a child and children tend to accept the world around them. His mother is everything; his world.

Each trip to the village entails a march through the snow, snow up to the eaves. Traipsing through the snowdrifts to get to the village, our Se-young sees a female adult world unfold in front of him through his mother and the vagrant girl, Sam-rae, who showed up in their open kitchen one particularly bitter winter night. The story itself unfolds at a plodding pace, a metronome ticking through the short story's brief 124 pages.

It is a bit more than simply a short story. Short stories simply open a brief window onto the protagonists' lives. In this case, however, it covers three parts: an episode when he was 13 years old and his mother accepted a vagrant young girl; happenings that occur the next winter; and then a final denouement. So it's a bit more than a mere short story, but it's not quite a novel. Maybe a "novella" would be an appropriate term for it, for it's a long short-story with an actual plot, more than just a window opening. So bring your snow boots.

For authors born in the 1930s, like Kim Joo-young (b. 1939) or Park Wan-suh (b. 1931) or others, their teens and 20s were dominated by independence, civil war, international war and a foreign military presence. Economic growth and opportunities outside the village didn't come about until these authors were in their mid-30s or 40s, in the 1960s and 1970s. They were middle-aged when the roller coaster of wealth-generation and social progress grew in the 1970s and 1980s. Indeed, arriving at their 60s in the 1990s, it's reasonable to see how many of these authors would feel as if they were on top of the world. They were direct witnesses to society as it grew out of dirt, developed agriculture, developed industry, conquered dictatorship, fostered democracy, honed technologies and reached out to the world and up to the skies. Born with no processed paper products and no toilet paper, now their grandchildren were studying in Sydney or Vancouver, chatting on a smartphone with grandma and grandpa. Scars and trauma, yes; detentions, beatings and tear gas, yes; separated families and children given up to adoption, yes; but most who lived through it would argue that it was worth it. That's the roller coaster, a typhoon of a life.

With this in mind, much of Kim Joo-young's writings in "Stingray" (1998) are on par with his peer Park Wan-suh and her novel "Who Ate Up All the Shinga?" (1992). Park perhaps wrote a grander or loftier tale, but "Stingray" is its own product, a different product. Both cover childhood in Korea in the middle parts of the 20th century. Kim creates a shorter work with his spotlight more tightly focused. There's little outside the snow, his mother, the vagrant girl and the neighbor's dog leaping through the snow.

The two strong female characters are archetypes, to some degree, and yet both show this "toughness" in their own ways. The mother is the tough matron. The vagrant girl is the tough rebel. How can a woman survive in this world? What tools, tricks and techniques must you use if you're not male, if you're not educated, if you didn't inherit wealth and if you're not born in the big city. Narrator Se-young sees two examples of how to survive, and watches the two tough women dance and fight and dance around him.

The Donga-Ilbo, a newspaper, has said of "Stingray" that, "[It] should be savored, read slowly... the author has managed a perfect reproduction of the way people spoke in the late premodern era, relying on circumlocution rather than direct statement... the beauty of silence and metaphor both are presented wonderfully due to the author's exquisite craftsmanship."

On page 8, "A dried stingray, covered with soot and always hanging down from the kitchen doorjamb, had disappeared." It was the vagrant girl Sam-rae who took the dried snack, locking herself into this new family of Se-young and his mother. From there, the tale unfolds in the snows of rural Korea. As mentioned, bring your snow boots.

To read this tale, you could go to the library and find a copy of the summer 1998 issue of Author's World, or perhaps Writer's World, one of Seoul's literary magazines. Kim Joo-young (b. 1939) was 59-years-old that year and he was writing about his youth, a long article or a short novella for a literary periodical.

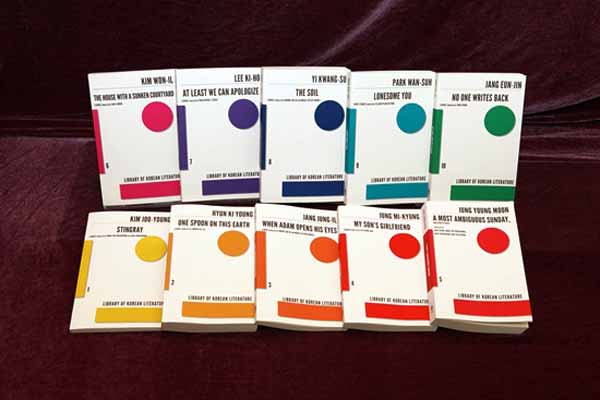

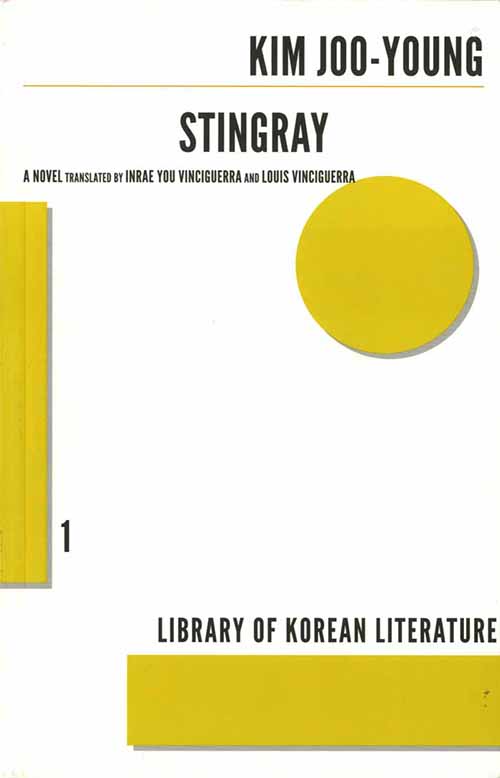

For English readers, the Library of Korean Literature is put out by the Dalkey Archive Press. "Stingray" was published in English in 2013 and was translated by Inrae You Vinciguerra and Louis Vinciguerra. The paperback is available at Amazon for USD 14.00, as are many other volumes from the Library of Korean Literature.

Kim Joo-young gives us two archetypes of women finding a survival path in a world not made for them. He wraps it in rural poverty and deep snow, but in the end, the reader smiles.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Literature Translation Institute of Korea

gceaves@korea.kr

Dalkey Archive Press puts out the Library of Korean Literature.

The world Kim creates of early 1950s rural, mountainous, wintery Korea is one of fierce pride, bitter grudges, village in-fighting, family control, rumors upon rumors, and people who actually listen to rumors. Power, jealousy and anger are all there is. Seen from the 13-year-old boy Se-young's eyes -- presumably the author himself -- the adult world is one of suffering, keeping up with the Joneses and a farcical belief in "face" and "honor" to one's own detriment, as if what other people think is actually important. Caring is shown through beatings and chastisement, and the snows keep piling up outside, trapping our three main protagonists in a rural home, a rural village, a small village bar shining like a lit fish bowl, as cabin fever rises.

In this adult world of village in-fighting lives our narrator Se-young. It is his flights of fancy, his imagination, that give bits of color to the tale. He sees wings sprouting from his mother's back, a particularly touching scene. Lay that imagery down on Freud's couch and you can see that he does love his mother and that he sees that she has done much for him and for his future success. He makes friends with the neighbor's dog, a leaping galumphing beast that licks and laughs and barks. He tracks down the vagrant girl who becomes a quasi big sister. He is a child and children tend to accept the world around them. His mother is everything; his world.

Each trip to the village entails a march through the snow, snow up to the eaves. Traipsing through the snowdrifts to get to the village, our Se-young sees a female adult world unfold in front of him through his mother and the vagrant girl, Sam-rae, who showed up in their open kitchen one particularly bitter winter night. The story itself unfolds at a plodding pace, a metronome ticking through the short story's brief 124 pages.

It is a bit more than simply a short story. Short stories simply open a brief window onto the protagonists' lives. In this case, however, it covers three parts: an episode when he was 13 years old and his mother accepted a vagrant young girl; happenings that occur the next winter; and then a final denouement. So it's a bit more than a mere short story, but it's not quite a novel. Maybe a "novella" would be an appropriate term for it, for it's a long short-story with an actual plot, more than just a window opening. So bring your snow boots.

For authors born in the 1930s, like Kim Joo-young (b. 1939) or Park Wan-suh (b. 1931) or others, their teens and 20s were dominated by independence, civil war, international war and a foreign military presence. Economic growth and opportunities outside the village didn't come about until these authors were in their mid-30s or 40s, in the 1960s and 1970s. They were middle-aged when the roller coaster of wealth-generation and social progress grew in the 1970s and 1980s. Indeed, arriving at their 60s in the 1990s, it's reasonable to see how many of these authors would feel as if they were on top of the world. They were direct witnesses to society as it grew out of dirt, developed agriculture, developed industry, conquered dictatorship, fostered democracy, honed technologies and reached out to the world and up to the skies. Born with no processed paper products and no toilet paper, now their grandchildren were studying in Sydney or Vancouver, chatting on a smartphone with grandma and grandpa. Scars and trauma, yes; detentions, beatings and tear gas, yes; separated families and children given up to adoption, yes; but most who lived through it would argue that it was worth it. That's the roller coaster, a typhoon of a life.

With this in mind, much of Kim Joo-young's writings in "Stingray" (1998) are on par with his peer Park Wan-suh and her novel "Who Ate Up All the Shinga?" (1992). Park perhaps wrote a grander or loftier tale, but "Stingray" is its own product, a different product. Both cover childhood in Korea in the middle parts of the 20th century. Kim creates a shorter work with his spotlight more tightly focused. There's little outside the snow, his mother, the vagrant girl and the neighbor's dog leaping through the snow.

The two strong female characters are archetypes, to some degree, and yet both show this "toughness" in their own ways. The mother is the tough matron. The vagrant girl is the tough rebel. How can a woman survive in this world? What tools, tricks and techniques must you use if you're not male, if you're not educated, if you didn't inherit wealth and if you're not born in the big city. Narrator Se-young sees two examples of how to survive, and watches the two tough women dance and fight and dance around him.

The Donga-Ilbo, a newspaper, has said of "Stingray" that, "[It] should be savored, read slowly... the author has managed a perfect reproduction of the way people spoke in the late premodern era, relying on circumlocution rather than direct statement... the beauty of silence and metaphor both are presented wonderfully due to the author's exquisite craftsmanship."

On page 8, "A dried stingray, covered with soot and always hanging down from the kitchen doorjamb, had disappeared." It was the vagrant girl Sam-rae who took the dried snack, locking herself into this new family of Se-young and his mother. From there, the tale unfolds in the snows of rural Korea. As mentioned, bring your snow boots.

To read this tale, you could go to the library and find a copy of the summer 1998 issue of Author's World, or perhaps Writer's World, one of Seoul's literary magazines. Kim Joo-young (b. 1939) was 59-years-old that year and he was writing about his youth, a long article or a short novella for a literary periodical.

'Stingray' is published in English in 2013 and is translated by Inrae You Vinciguerra and Louis Vinciguerra. The ebook is available at Amazon.

For English readers, the Library of Korean Literature is put out by the Dalkey Archive Press. "Stingray" was published in English in 2013 and was translated by Inrae You Vinciguerra and Louis Vinciguerra. The paperback is available at Amazon for USD 14.00, as are many other volumes from the Library of Korean Literature.

Kim Joo-young gives us two archetypes of women finding a survival path in a world not made for them. He wraps it in rural poverty and deep snow, but in the end, the reader smiles.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Literature Translation Institute of Korea

gceaves@korea.kr

Most popular

- Military discharge sets stage for reunion of all 7 BTS members

- 'We are back!' BTS Festa heralds hyped return of K-pop phenom

- Presidents Lee, Trump discuss tariff deal in first phone talks

- 'Maybe Happy Ending' wins 6 Tonys including Best Musical

- President Lee leaves for G7 Summit in Canada on first int'l trip