By Jeon Han

Photo = Seoul Museum of History

Illustrated = Manus Eugune

"Koreans Declare Independence."

This was the headline of a New York Times article dated March 13, 1919. Of two stories datelined in Beijing, China, and Seoul and wired on March 12 the same year, the Seoul-datelined Associated Press (AP) article at the bottom is about the Declaration of Independence of Joseon (Korea) cabled by Albert Wilder Taylor (1875-1948), an American businessman.

Taylor's wiring of Korea's Declaration of Independence was nothing less than a historical necessity. A number of records describe him as a correspondent or reporter but his original vocation was in mining.

According to the Dilkusha & Chain of Amber art catalog of the Special Exhibition of Donated Relics organized by the Seoul Museum of History, data from 1935 on the annual lists of Westerners and consular officials in Joseon published by the Office of the Governor-General of Korea said Taylor, whose residence was in Hongpa-dong 1, Gyeongseong-bu, put mining as his occupation. Even without these records, he is known to have engaged in excavating and running gold mines.

No accurate records exist on when Taylor began to wire news about Korea or his motives for doing so, but details are available on how he obtained copies of the declaration and wrote stories on Korea.

Albert W. Taylor was 42 and his wife Mary Taylor 28 when they first came to Korea in 1917.

What is known is that Taylor accepted a correspondent job after dropping in at the Chosun Hotel on Feb. 28, 1919. He had heard from a person based in Tokyo that someone was being sought to cover the funeral of Korean Emperor Gojong.

The same day, Taylor's son was born at Severance Hospital in Seoul. After seeing nurses hide printed copies of the Declaration of Independence under the bed of a room exclusively for foreign patients, he obtained a copy and sent it to The AP's Tokyo bureau.

Taylor, who had broken the news to the world about Korea's drive for independence through writing articles on the declaration and the March First Independence Movement, said in a March 7 letter sent to his mother-in-law, "I didn’t apply for the job but was named The AP's Korea correspondent. I was busy with my work until recently, covering the state funeral of the recently deceased Korean (emperor) and writing stories about Korea's independence movement."

As he wrote in the letter, Taylor covered the funeral on March 3 right after the movement broke out. While confirming whether his stories on the funeral were run in newspapers is impossible, the photos he took of scenes from Gyeongbokgung Palace to Heunginjimun Gate show vivid images.

Photos of Emperor Gojong's funeral taken by Albert W. Taylor

Covering Japan's Atrocities and Korea's Independence Movement

Taylor produced follow-up reports on the movement after covering Emperor Gojong's funeral. He traveled to the scene of the so-called Jeam-ri Massacre, in which Japanese soldiers herded residents into a church in the village of Jeam-ri in Hwaseong, Gyeonggi-do Province, and slaughtered them in retaliation for the movement.

His story on the massacre was run on the April 24 edition of The New York Times under the headline "Say Japanese Troops Massacred Koreans," and the Japan Advertiser, an English-language newspaper published in Japan, also carried the story on April 27 and 29.

Taylor's name was not mentioned in the story but his coverage was noted in documents of the U.S. government and a report authored by Horace Horton Underwood (1880-1951), who was a pioneer in higher education in Korea.

American consul Raymond Curtice wrote in an April 21 report that he visited the scene of the massacre on April 16 with The AP's Seoul correspondent A.W. Taylor, and Underwood in his report said he did the same with Curtice and Taylor.

Aside from the massacre, Taylor also covered trials of independence fighters who led the movement. A story on the trials of Son Byung-hee (1861-1922) and others ran on the July 13, 1920, edition of The Dong-A Ilbo. It read, "A Westerner appeared in the press box for the first time. This man was Taylor, a correspondent of the American news agency AP, who will break news on the trials."

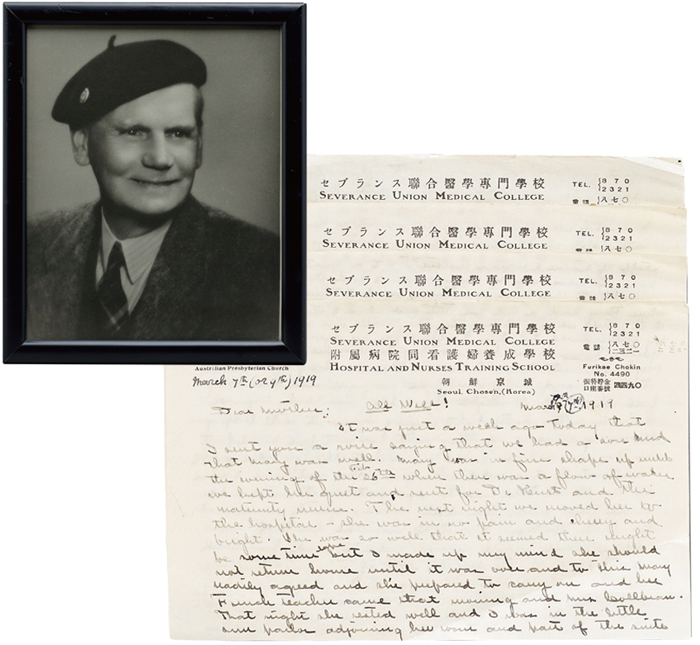

A picture of Albert W. Taylor in the 1940s and a letter he sent to his mother-in-law about his job to report the March First Independence Movement are kept in Korea as part of his legacy.

Deportation and Demise

Few remaining records mention what Taylor covered and wrote as a correspondent after 1920. What can be inferred without difficulty, however, is what Joseon meant to him.

In 1923, he built a two-story red-brick house with a basement in Seoul's Haengchon-dong neighborhood on the site where Gen. Gwon Yul's home is known to have been, and carved the Sanskrit word "Dilkusha," meaning "heart of delight," into the foundation.

Taylor lived in Seoul with his wife Mary Linley Taylor (1889-1982) and their son Bruce Tickell Taylor (1919-2015), but they were deported in 1942 as Japan's imperialism neared its peak.

After Japan's surrender in 1945, Taylor made every effort to return to Korea, sending letters to the U.S. administration and American military authorities there. Unfortunately, he died of a sudden heart attack in 1948. His widow brought his ashes to Korea in September the same year and interred them at Yanghwajin Foreign Missionary Cemetery in Seoul.

Dilkusha (meaning "heart of delight" in Sanskrit) House, where Albert W. Taylor’s family used to live in Seoul, has been restored.

hanjeon@korea.kr

Most popular

- Military discharge sets stage for reunion of all 7 BTS members

- 'We are back!' BTS Festa heralds hyped return of K-pop phenom

- K-pop streaming on Spotify skyrockets 470-fold in 10 years

- Presidents Lee, Trump discuss tariff deal in first phone talks

- President Lee leaves for G7 Summit in Canada on first int'l trip