Paul Kajander, a 34-year-old Canadian artist living in Seoul, often pays a visit to Euljiro Street. He finds inspiration from the numerous light stores and light displays placed by these stores on the street.

Since moving to Seoul from Vancouver in 2011, Kajander has been working on video and installation art works. Last summer, he took part in the Universal Studios exhibition involving art by non-Korean artists living in Korea at the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA).

Like many artists who lead a nomadic life and work in diverse cultures, Kajander gets his inspiration by living in Korea and expresses what he has experienced in Korea through his art.

Kajander heard about Seoul from his friends who took part in the Mediacity Seoul exhibit in 2010 and decided to move to the city. He said that Seoul is a great city in which to do creative work and that, now, it feels like home.

He has been using various media, including video and photography, to create his installation art works. He uses such diverse media and materials, "Because it allows you to be flexible in layering content. Also, I like the complexity. I like feelings of doubt."

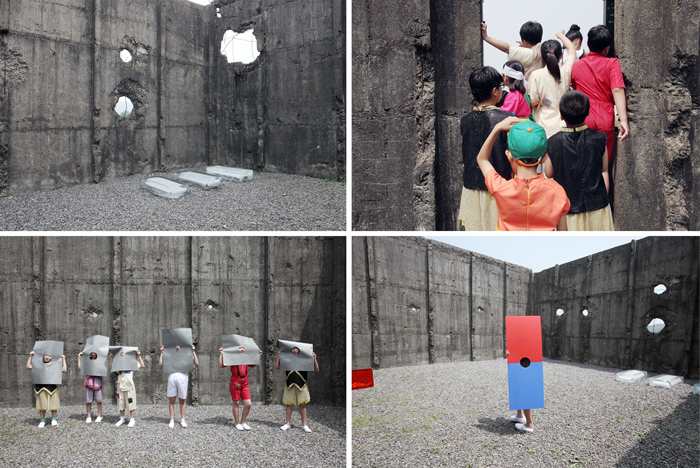

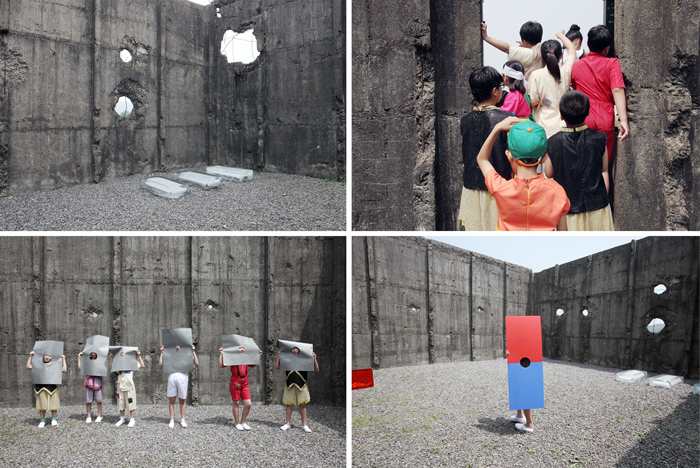

He has a great deal of interest in Korean history, society and arts. Last year, he took part in the "Real DMZ Project" and worked with elementary school students living in Cherwon County, Gangwon-do (Gangwon Province), near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that divides the Korean Peninsula. He took photographs of local children within the ruins of an ice warehouse devastated by the Korean War (1950-1953).

"It is an opportunity and responsibility to reflect on the conditions of the world and the state of the world at this time," said Kajander. "It is a way to organize reality and yourself in relation to reality," he said, adding that he wants to encourage thought and contemplation through his work.

Kajander was interviewed at his studio in Sinsa-dong, southern Seoul, and asked how he decided to move to Korea and what he thinks of art.

- Why did you move to Seoul to work as an artist?

It was curiosity mixed with desperation, and I decided to work and stay here because it was a good chance to explore a different part of the world. My curiosity came from friends who took part in the Mediacity Seoul exhibition in 2010. I knew a little about Seoul from films and history, like the Korean War and the division of the peninsula. I’ve been interested in world cinema for a while and Korean directors have been making great films.

- You worked in New York and Tokyo. What's it like to do creative work in Seoul?

Seoul is great in the sense that it is an interesting place to work, to think about materials and to think about culture and politics. I have only been involved in a few small projects in Japan and New York. It’s hard to compare short trips with my time in Seoul, which is becoming more like home. I never thought that New York or Tokyo would be a home base. I only went there to do some projects or to take part in residence programs, but I never moved there.

When you are based somewhere, it is different from when you are visiting. When you visit somewhere, you have a limited routine as to where you go, such as the museum or gallery. When you are based somewhere, however, you know the city in a complex way. You become aware of the city and it offers possibilities to learn about the city and to explore different parts of the city that are unfamiliar to you.

- Why did you become an artist? Are there people who influenced you to become an artist?

It is a complicated question. The role of the artist now is determined by your relationship with culture and society. When I was young, I was curious about participating in a culture that was strange to me. If you are an artist, you can definitely think differently about the economic relationship to labor.

When you are young and you make drawings, for instance, people might say, “you’re so talented.” That kind of influence shaped my sense of identity. When I finally chose to go to art school, reality started kicking in. When you are 18 years old, what you do in art is very different from what you do when you are 34. My perspective on art has changed a lot since then. Actually, I don't know why or when I first made the decision, but I am glad that I continue to work as an artist.

There are a many people who influenced me a lot along the way. When I was studying for my undergrad, I met my teacher Judy Radul in about 1998. She remains a powerful figure for me in terms of thinking about art and how one might choose to live their life. I have a lot of admiration for how she works and how she thinks through her work. Although I met her as a teacher, she later became a friend.

- Why did you choose media and installation art among others?

Generally, I think of my work as different layers of being, either material or durational. A lot of the time, I use videos, which allow you to do something very unique. In videos, sound, space and language can happen all at once. In a video, you can show an image, have actors speak and manipulate the soundtrack simultaneously. Each of these generates a meaning that is more complex than its individual parts. Then there is montage. I want viewers to be taken on many different lines of sight. Mostly, I work from research or else I encounter something in the world and it works as a trigger for me to make something else.

- Why do you use various materials and genres, such as painting, sculpture and video, to create your works?

Media and installation art allows me to do and make different things. You can incorporate different objects, images, times and durations. Video and sound seem to offer a way to reflect on technology’s presence in daily life. For instance, when we are on the subway, we can see LCD screens everywhere and people watching TV on their smartphones. Media has saturated and perhaps dominates our attention, especially in Seoul.

I know that every person approaches everything differently. There is an amazing poet whose name is C. A. Conrad. His introduction to a book of poems says it very well: if you have one poem, but thousands of people read it, there will be 1,000 poems. This is because each person is the result of their experience, knowledge, personal beliefs and everything else we carry within us.

I love it when people who are not educated in art, but who are open-minded, see a work and say the most amazing things about it. They can be really observant and find one element of your work that is really meaningful for them because they can grab it. In many ways, this is the most useful part of having an exhibition.

- Last year, you took part in the "Real DMZ Project" in Cherwon County, Gangwon-do, near the Demilitarized Zone. You worked with elementary school children living in Cherwon County. What kind of message were you trying to deliver?

In that case, it was more about being presented with an opportunity for a very specific context. I had the chance to visit there many times. The message in that work is kind of complex. It comes down to the atrocities and violence that happened there on a large scale, and which has left so many psychological scars. I could feel that in Cherwon, however, my knowledge can only come from second-hand information, oral histories, textbooks, films, documents and media representations of war.

I wanted to work with children who grew up there. They were totally children of this time. They had smartphones and were often distracted by video games. Where they live, however, you often see tanks driving along the road. They were living right here in proximity to the situation. I wanted to talk to these children and ask what freedom means to them and how they think about life.

- You took part in the International Artists Residency Program supported by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA). How did you participate in the program and what did you gain from the program?

I thought it would be a great opportunity to work and meet other international artists so I applied for the residency program. Korea has some of the best opportunities for residence programs. Korean residency programs often have a nice mix of both non-Korean and Korean artists, though I wish more dialogue were possible between the two.

For an artist anywhere, having time to work is the most important thing and doing this in Seoul is a great opportunity. Participating at the MMCA Changdong was great because I learned that it is really important for me to have a material space. I have been uprooted many times recently and I lost a sense of being based in one location. The residency program gave me the chance to work materially in a great space. Without this opportunity, I don’t think I would have experimented with so many object-oriented sculptures.

- You exhibited "Lights Lit for Show" at the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA) for the Universal Studios show last summer. How did you come up with that work?

That work is made up of photographic light-boxes that depict the lighting displays found along Euljiro. The photos act like low level outdoor advertisements, the kind you see outside restaurants or shops. The subject of the work is the hand-made lighting displays that light vendors install outside their shops along Euljiro. I always love to visit Euljiro and to see these.

These displays are each unique and have obviously been put together by the shop owners. Making provisional advertising light-boxes like these is a bit of a tongue-in-cheek joke, considering the photographic light-box and its relationship to advertising and art history. I also made them to document these fascinating and idiosyncratic sculptures. They are really something I love about this neighborhood. It's an earlier form of trade and commercial display, as if Home Depot exploded.

- In what kind of subjects are you most interested? What kind of projects are you working on or planning to do?

I have been thinking a lot about 3-D film and I am currently working on a project that may involve this curiosity. I am going to take part in the New Forms Festival in Vancouver in August and my work will likely be a 3-D video screening with sound components.

When I was in New York recently, I saw Ken Jacobs’ incredible screening at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC). He’s been working with consumer grade 3-D video and freeze-frame, as well as other forms of optical manipulation. I also recently saw Jean-Luc Godard‘s latest film, which is also in 3-D, which was an interesting use and dismantling of the illusion of depth. As technology evolves, a lot of media becomes more accessible.

- Where do you get your inspiration from, such as from Korean society or history? What do you do to find inspiration?

I take a lot of inspiration from reading. As for interesting places in Korea, as I said, Euljiro remains really fascinating to me. I like walking, so I sometimes go to the mountains in the suburbs just to wind down. When I lived in Bukchon, in northern Seoul, I walked along the secret garden wall near the end of Changdeokgung Palace for night-time walks. That was my favorite walking route during the hot summer nights. There are a lot of trees, so it is quite cool. Since I moved to near Beotigogae Station, I started walking along the fortress trail, which is an interesting convergence between Namsan Mountain and the meandering fortress wall with the modern hotels like the Shilla Hotel and the Banyan Tree Club & Spa that are nearby. Walking is a source of inspiration.

- What does Korea and art mean to you?

Art means everything to me. It is a way to come up with new questions. Art means a lot of struggle and pleasure. Good artists honestly reflect the conditions of being in the world today and contemporary art can be meaningful in helping people to think about society. Only human beings seem to create art. It is a very unique form of consciousness.

To me, Korea involves a lot of contradiction. Vancouver is a multicultural city. In the subway in Seoul, however, everyone knows that I am not Korean. It is a useful experience. You are always aware of who you are and how you behave. It is like inverting your sense of taking your anonymity for granted. Korea has been instructive in that regard.

By Limb Jae-un

Photos: Jeon Han

Korea.net Staff Writers

jun2@korea.kr

Since moving to Seoul from Vancouver in 2011, Kajander has been working on video and installation art works. Last summer, he took part in the Universal Studios exhibition involving art by non-Korean artists living in Korea at the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA).

Like many artists who lead a nomadic life and work in diverse cultures, Kajander gets his inspiration by living in Korea and expresses what he has experienced in Korea through his art.

Canadian media and installation artist Paul Kajander

Kajander heard about Seoul from his friends who took part in the Mediacity Seoul exhibit in 2010 and decided to move to the city. He said that Seoul is a great city in which to do creative work and that, now, it feels like home.

He has been using various media, including video and photography, to create his installation art works. He uses such diverse media and materials, "Because it allows you to be flexible in layering content. Also, I like the complexity. I like feelings of doubt."

He has a great deal of interest in Korean history, society and arts. Last year, he took part in the "Real DMZ Project" and worked with elementary school students living in Cherwon County, Gangwon-do (Gangwon Province), near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) that divides the Korean Peninsula. He took photographs of local children within the ruins of an ice warehouse devastated by the Korean War (1950-1953).

"It is an opportunity and responsibility to reflect on the conditions of the world and the state of the world at this time," said Kajander. "It is a way to organize reality and yourself in relation to reality," he said, adding that he wants to encourage thought and contemplation through his work.

Kajander was interviewed at his studio in Sinsa-dong, southern Seoul, and asked how he decided to move to Korea and what he thinks of art.

- Why did you move to Seoul to work as an artist?

It was curiosity mixed with desperation, and I decided to work and stay here because it was a good chance to explore a different part of the world. My curiosity came from friends who took part in the Mediacity Seoul exhibition in 2010. I knew a little about Seoul from films and history, like the Korean War and the division of the peninsula. I’ve been interested in world cinema for a while and Korean directors have been making great films.

- You worked in New York and Tokyo. What's it like to do creative work in Seoul?

Seoul is great in the sense that it is an interesting place to work, to think about materials and to think about culture and politics. I have only been involved in a few small projects in Japan and New York. It’s hard to compare short trips with my time in Seoul, which is becoming more like home. I never thought that New York or Tokyo would be a home base. I only went there to do some projects or to take part in residence programs, but I never moved there.

When you are based somewhere, it is different from when you are visiting. When you visit somewhere, you have a limited routine as to where you go, such as the museum or gallery. When you are based somewhere, however, you know the city in a complex way. You become aware of the city and it offers possibilities to learn about the city and to explore different parts of the city that are unfamiliar to you.

Paul Kajander says he does not remember how and when he decided to become an artist, but that he is glad he did.

- Why did you become an artist? Are there people who influenced you to become an artist?

It is a complicated question. The role of the artist now is determined by your relationship with culture and society. When I was young, I was curious about participating in a culture that was strange to me. If you are an artist, you can definitely think differently about the economic relationship to labor.

When you are young and you make drawings, for instance, people might say, “you’re so talented.” That kind of influence shaped my sense of identity. When I finally chose to go to art school, reality started kicking in. When you are 18 years old, what you do in art is very different from what you do when you are 34. My perspective on art has changed a lot since then. Actually, I don't know why or when I first made the decision, but I am glad that I continue to work as an artist.

There are a many people who influenced me a lot along the way. When I was studying for my undergrad, I met my teacher Judy Radul in about 1998. She remains a powerful figure for me in terms of thinking about art and how one might choose to live their life. I have a lot of admiration for how she works and how she thinks through her work. Although I met her as a teacher, she later became a friend.

- Why did you choose media and installation art among others?

Generally, I think of my work as different layers of being, either material or durational. A lot of the time, I use videos, which allow you to do something very unique. In videos, sound, space and language can happen all at once. In a video, you can show an image, have actors speak and manipulate the soundtrack simultaneously. Each of these generates a meaning that is more complex than its individual parts. Then there is montage. I want viewers to be taken on many different lines of sight. Mostly, I work from research or else I encounter something in the world and it works as a trigger for me to make something else.

Paul Kajander poses for a photo at his studio in Sinsa-dong, southern Seoul.

- Why do you use various materials and genres, such as painting, sculpture and video, to create your works?

Media and installation art allows me to do and make different things. You can incorporate different objects, images, times and durations. Video and sound seem to offer a way to reflect on technology’s presence in daily life. For instance, when we are on the subway, we can see LCD screens everywhere and people watching TV on their smartphones. Media has saturated and perhaps dominates our attention, especially in Seoul.

I know that every person approaches everything differently. There is an amazing poet whose name is C. A. Conrad. His introduction to a book of poems says it very well: if you have one poem, but thousands of people read it, there will be 1,000 poems. This is because each person is the result of their experience, knowledge, personal beliefs and everything else we carry within us.

I love it when people who are not educated in art, but who are open-minded, see a work and say the most amazing things about it. They can be really observant and find one element of your work that is really meaningful for them because they can grab it. In many ways, this is the most useful part of having an exhibition.

Last year's 'The Real DMZ Project' by Paul Kajander involves elementary school students living in Cherwon, Gangwon-do, and a range of materials and media. (photos courtesy of Paul Kajander)

- Last year, you took part in the "Real DMZ Project" in Cherwon County, Gangwon-do, near the Demilitarized Zone. You worked with elementary school children living in Cherwon County. What kind of message were you trying to deliver?

In that case, it was more about being presented with an opportunity for a very specific context. I had the chance to visit there many times. The message in that work is kind of complex. It comes down to the atrocities and violence that happened there on a large scale, and which has left so many psychological scars. I could feel that in Cherwon, however, my knowledge can only come from second-hand information, oral histories, textbooks, films, documents and media representations of war.

I wanted to work with children who grew up there. They were totally children of this time. They had smartphones and were often distracted by video games. Where they live, however, you often see tanks driving along the road. They were living right here in proximity to the situation. I wanted to talk to these children and ask what freedom means to them and how they think about life.

- You took part in the International Artists Residency Program supported by the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA). How did you participate in the program and what did you gain from the program?

I thought it would be a great opportunity to work and meet other international artists so I applied for the residency program. Korea has some of the best opportunities for residence programs. Korean residency programs often have a nice mix of both non-Korean and Korean artists, though I wish more dialogue were possible between the two.

For an artist anywhere, having time to work is the most important thing and doing this in Seoul is a great opportunity. Participating at the MMCA Changdong was great because I learned that it is really important for me to have a material space. I have been uprooted many times recently and I lost a sense of being based in one location. The residency program gave me the chance to work materially in a great space. Without this opportunity, I don’t think I would have experimented with so many object-oriented sculptures.

The 'Lights Lit for Show' works by Paul Kajander are photographs of light box displays on the streets of Euljiro. The photographs are printed on latex. (photos courtesy of Paul Kajander)

- You exhibited "Lights Lit for Show" at the Seoul Museum of Art (SeMA) for the Universal Studios show last summer. How did you come up with that work?

That work is made up of photographic light-boxes that depict the lighting displays found along Euljiro. The photos act like low level outdoor advertisements, the kind you see outside restaurants or shops. The subject of the work is the hand-made lighting displays that light vendors install outside their shops along Euljiro. I always love to visit Euljiro and to see these.

These displays are each unique and have obviously been put together by the shop owners. Making provisional advertising light-boxes like these is a bit of a tongue-in-cheek joke, considering the photographic light-box and its relationship to advertising and art history. I also made them to document these fascinating and idiosyncratic sculptures. They are really something I love about this neighborhood. It's an earlier form of trade and commercial display, as if Home Depot exploded.

- In what kind of subjects are you most interested? What kind of projects are you working on or planning to do?

I have been thinking a lot about 3-D film and I am currently working on a project that may involve this curiosity. I am going to take part in the New Forms Festival in Vancouver in August and my work will likely be a 3-D video screening with sound components.

When I was in New York recently, I saw Ken Jacobs’ incredible screening at the Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC). He’s been working with consumer grade 3-D video and freeze-frame, as well as other forms of optical manipulation. I also recently saw Jean-Luc Godard‘s latest film, which is also in 3-D, which was an interesting use and dismantling of the illusion of depth. As technology evolves, a lot of media becomes more accessible.

- Where do you get your inspiration from, such as from Korean society or history? What do you do to find inspiration?

I take a lot of inspiration from reading. As for interesting places in Korea, as I said, Euljiro remains really fascinating to me. I like walking, so I sometimes go to the mountains in the suburbs just to wind down. When I lived in Bukchon, in northern Seoul, I walked along the secret garden wall near the end of Changdeokgung Palace for night-time walks. That was my favorite walking route during the hot summer nights. There are a lot of trees, so it is quite cool. Since I moved to near Beotigogae Station, I started walking along the fortress trail, which is an interesting convergence between Namsan Mountain and the meandering fortress wall with the modern hotels like the Shilla Hotel and the Banyan Tree Club & Spa that are nearby. Walking is a source of inspiration.

Paul Kajander says living in Korea makes him always conscious of being a foreigner.

- What does Korea and art mean to you?

Art means everything to me. It is a way to come up with new questions. Art means a lot of struggle and pleasure. Good artists honestly reflect the conditions of being in the world today and contemporary art can be meaningful in helping people to think about society. Only human beings seem to create art. It is a very unique form of consciousness.

To me, Korea involves a lot of contradiction. Vancouver is a multicultural city. In the subway in Seoul, however, everyone knows that I am not Korean. It is a useful experience. You are always aware of who you are and how you behave. It is like inverting your sense of taking your anonymity for granted. Korea has been instructive in that regard.

By Limb Jae-un

Photos: Jeon Han

Korea.net Staff Writers

jun2@korea.kr