View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

This is the eighth part in our series, “Onggi, traditional earthenware vessel in Korea.”

Master Craftsmen

The style of pottery prominent today has been handed down since the early Joseon era. Some 500 years have passed, but production methods, the shape of the urns and the style of usage for the large containers all remain largely similar, with records both written and unwritten being kept alive throughout the years. Across the centuries, pottery has remained an essential housekeeping container in many homes.

In the annals of history, however, there is very little about the life of the master potters themselves. During the class-conscious Joseon times, pottery craftsmen were generally disdained by society at large and were treated as outcasts.

Master Craftsmen and the Catholic Church

Originally, potters did not receive much respect for their work. During the later years of the Joseon Dynasty, however, the gradual increase in population lead to a broadening of the uses for pottery. This called for an increase in artisans skilled at making pottery.

A particularly noticeable fact is that during the later years of the Joseon Dynasty, there were many master potters who had converted to Catholicism. This fact is closely related to the history of the Catholic Church in Korea. Converts to this branch of Christianity were severely persecuted by the ruling dynasty, ever since Catholicism was introduced to the country in the late 18th century.

Early converts to Catholicism formed Catholic communities in secluded regions to hide from government persecution. These groups slowly adopted pottery as their craft, allowing them to make a living. Also, many traditional potters joined these Catholic communities as well. Because potters were already disdained by mainstream Joseon society, and building upon the foundational Christian belief in equality, they found the new Western religion to be appealing, as it offered them consolation. Even today, there are many Catholic descendants of late Joseon era potters.

Traditional Potters in Modern Times

During the early 20th century and under Japanese occupation, pottery found a place in the modernizing economy and became an industry. There was a great increase in both supply and demand for the large urns. Life of the craftsmen, however, did not improve and their social status remained on the lower rungs. Businessmen owned the ceramic factories and hired potters off the streets to mass produce merchandise wholesale.

During the war in the early 1950s, the pottery business fell even further. With peace, however, there was a renewed demand for ceramic urns, as most of the old ones, in each and every home, had been shattered during the war.

Many potters today remember the late 1950s and early 1960s as a time when they could sell their ceramic wares faster than they could make them. The peak of the pottery industry was immediately after the Korean War.

Since the early 1970s, however, plastic and metal containers have been introduced into the modernized economy, and there has also been a broadening of the Korean palette as people rely less and less on fermented vegetables. Due to these macro trends, many potters have left the industry and have sought other lines of work.

Today, there are only a few master potters still producing traditional ceramic wares. Among them, Kim Il-man and Jeong Yoon-seok have both been designated as holders of intangible cultural heritage abilities. They have been recognized as true masters of traditional Korean pottery and today act as the vanguard for the restoration of traditional ceramics.

Kim Il-man

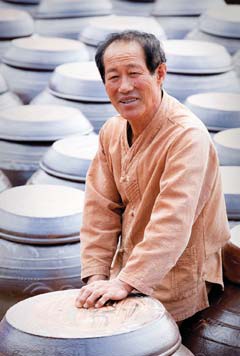

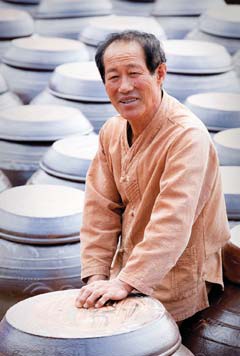

Kim Il-man

Master potter Kim Il-man produces pottery with his four sons. He signs his pottery works as Obuja Onggi. He almost quit the industry on numerous occasions, as running one's own pottery company can be trying at times. It was difficult for him to make ends meet, as at times there has been no demand for traditional ceramic wares.

However, he endured the difficult times and is still working in the field of pottery production. It was his pride as a master potter that helped get through the tough times. In modern times, he feels much better, as the popularity of traditional pottery has increased as the people have gotten richer. Also, since his designation as a holder of an intangible cultural heritage ability, the formal recognition by the Korean government has increased his standing in society.

Traditionally, Catholicism has been over represented in pottery circles. During the 19th century, believers in Catholicism were severely persecuted by the ruling dynasty and many converts became potters in an attempt to escape the persecution. Kim Il-man's parents were Catholic and were also potters. Following in his parents' footsteps, Kim himself started to learn the ceramic arts when he was 15 years old. Nowadays, there is a ceramic tombstone at his parents' grave, made by Kim himself.

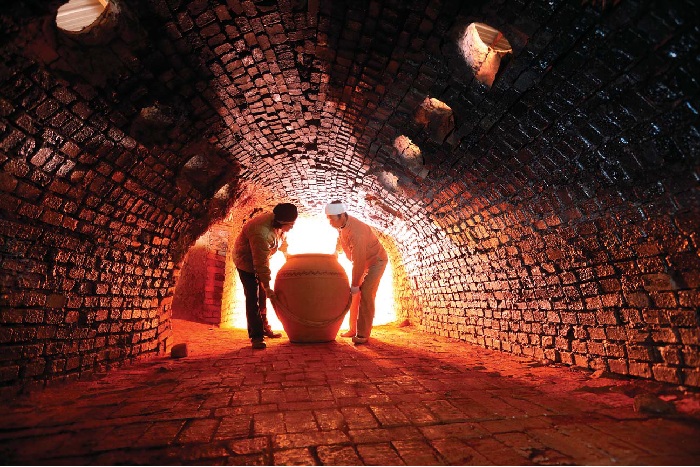

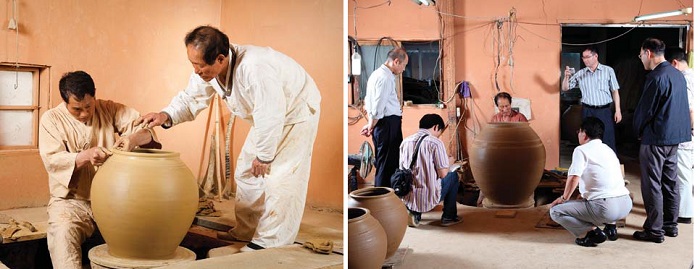

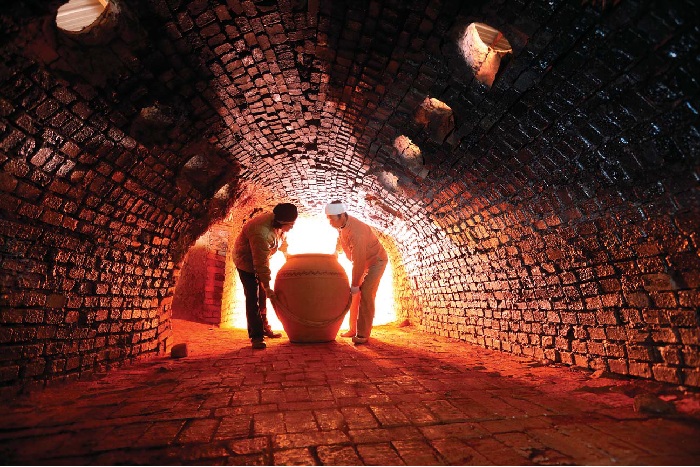

When the day comes to fire the unbaked pottery in the kiln, many of the workers who work alongside the master craftsmen are not present. So many potters rely on their extended family to get the work done on firing day.

Kim Il-man's youngest son manages the kiln fire, and his grandson looks on. His grandson could be on his way to becoming a master potter, as, just like Kim's son, he has grown up watching the pottery process go on all around him.

In 2010, Kim Il-man was designated as a holder of an important intangible cultural heritage ability. His sole desire these days is to see his sons carry on the tradition without him. He continually encourages his sons to work hard and to carry on the knowledge and skills which he imparted to them throughout his life.

Jeong Yoon-seok

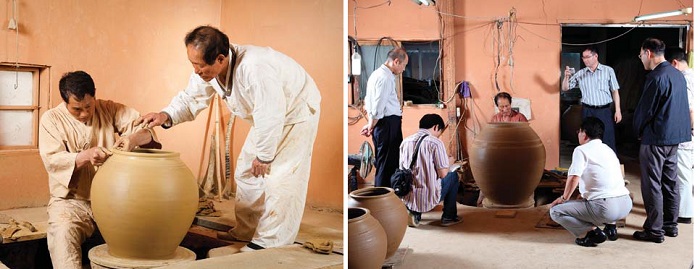

Jeong Yoon-seok

Master potter Jeong Yoon-seok has had a similar life to Kim Il-man. Jeong's pottery nom de plume is Gangjin Chilyang Onggi and he lives in the village of Bonghwang at the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula, abutting the seashore. Bonghwang is a traditional center of pottery and traditionally the boats anchored in the harbor were not fishing boats but trading vessels used to ship the ceramics and urns created there.

Due to its location, Bonghwang was not severely affected by the Korean War. With the arrival of peace, 30 ships a day carried the town's pottery products across the entire southern coastal region. Nowadays, however, with the country's and the economy's transformation, most master potters have left the famous town to find new jobs. There were one or two master craftsmen who stayed in the village, but many of them have by now passed away. Among all the masters and pottery experts from Bonghwang village, only Jeong Yoon-seok remains to carry on the tradition into modern times.

The village where Jeon has lived was once a thriving center for pottery and the ceramics trade. It is now simply a regular fishing village, but up until about 40 years ago its harbor had as many as 30 ships per day coming and going as the town shipped out to the world its prolific amount of pottery works.

In September 2010, the National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage hosted a reenactment of the harbor's pottery trade. The event saw many ceramic works made by Jeong Yoon-seok loaded onto traditional vessels and shipped from Gangjin to Yeosu, by way of Bonghwang.

Jeong Yoon-seok was against his son entering the traditional pottery trade upon his completion of military service. He did not want his son to walk down the same difficult life path that he had trodden. His son, however, said that it was even harder to sit by idly as such a great body of knowledge fades into extinction in his home town. So Jeong finally allowed his son to learn the trade and to become a potter.

In 2009, research began into Jeon's pottery skill and tradition and in 2010 he was awarded an official certificate that designated him as a holder of an important intangible cultural heritage ability.

*This series of article has been made possible through the cooperation of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. (Source: Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea)

Master Craftsmen

The style of pottery prominent today has been handed down since the early Joseon era. Some 500 years have passed, but production methods, the shape of the urns and the style of usage for the large containers all remain largely similar, with records both written and unwritten being kept alive throughout the years. Across the centuries, pottery has remained an essential housekeeping container in many homes.

In the annals of history, however, there is very little about the life of the master potters themselves. During the class-conscious Joseon times, pottery craftsmen were generally disdained by society at large and were treated as outcasts.

Master Craftsmen and the Catholic Church

Originally, potters did not receive much respect for their work. During the later years of the Joseon Dynasty, however, the gradual increase in population lead to a broadening of the uses for pottery. This called for an increase in artisans skilled at making pottery.

A particularly noticeable fact is that during the later years of the Joseon Dynasty, there were many master potters who had converted to Catholicism. This fact is closely related to the history of the Catholic Church in Korea. Converts to this branch of Christianity were severely persecuted by the ruling dynasty, ever since Catholicism was introduced to the country in the late 18th century.

Early converts to Catholicism formed Catholic communities in secluded regions to hide from government persecution. These groups slowly adopted pottery as their craft, allowing them to make a living. Also, many traditional potters joined these Catholic communities as well. Because potters were already disdained by mainstream Joseon society, and building upon the foundational Christian belief in equality, they found the new Western religion to be appealing, as it offered them consolation. Even today, there are many Catholic descendants of late Joseon era potters.

Traditional Potters in Modern Times

During the early 20th century and under Japanese occupation, pottery found a place in the modernizing economy and became an industry. There was a great increase in both supply and demand for the large urns. Life of the craftsmen, however, did not improve and their social status remained on the lower rungs. Businessmen owned the ceramic factories and hired potters off the streets to mass produce merchandise wholesale.

During the war in the early 1950s, the pottery business fell even further. With peace, however, there was a renewed demand for ceramic urns, as most of the old ones, in each and every home, had been shattered during the war.

Many potters today remember the late 1950s and early 1960s as a time when they could sell their ceramic wares faster than they could make them. The peak of the pottery industry was immediately after the Korean War.

Since the early 1970s, however, plastic and metal containers have been introduced into the modernized economy, and there has also been a broadening of the Korean palette as people rely less and less on fermented vegetables. Due to these macro trends, many potters have left the industry and have sought other lines of work.

Today, there are only a few master potters still producing traditional ceramic wares. Among them, Kim Il-man and Jeong Yoon-seok have both been designated as holders of intangible cultural heritage abilities. They have been recognized as true masters of traditional Korean pottery and today act as the vanguard for the restoration of traditional ceramics.

Master potter Kim Il-man produces pottery with his four sons. He signs his pottery works as Obuja Onggi. He almost quit the industry on numerous occasions, as running one's own pottery company can be trying at times. It was difficult for him to make ends meet, as at times there has been no demand for traditional ceramic wares.

However, he endured the difficult times and is still working in the field of pottery production. It was his pride as a master potter that helped get through the tough times. In modern times, he feels much better, as the popularity of traditional pottery has increased as the people have gotten richer. Also, since his designation as a holder of an intangible cultural heritage ability, the formal recognition by the Korean government has increased his standing in society.

Traditionally, Catholicism has been over represented in pottery circles. During the 19th century, believers in Catholicism were severely persecuted by the ruling dynasty and many converts became potters in an attempt to escape the persecution. Kim Il-man's parents were Catholic and were also potters. Following in his parents' footsteps, Kim himself started to learn the ceramic arts when he was 15 years old. Nowadays, there is a ceramic tombstone at his parents' grave, made by Kim himself.

When the day comes to fire the unbaked pottery in the kiln, many of the workers who work alongside the master craftsmen are not present. So many potters rely on their extended family to get the work done on firing day.

Kim Il-man's youngest son manages the kiln fire, and his grandson looks on. His grandson could be on his way to becoming a master potter, as, just like Kim's son, he has grown up watching the pottery process go on all around him.

In 2010, Kim Il-man was designated as a holder of an important intangible cultural heritage ability. His sole desire these days is to see his sons carry on the tradition without him. He continually encourages his sons to work hard and to carry on the knowledge and skills which he imparted to them throughout his life.

Master potter Jeong Yoon-seok has had a similar life to Kim Il-man. Jeong's pottery nom de plume is Gangjin Chilyang Onggi and he lives in the village of Bonghwang at the southern tip of the Korean Peninsula, abutting the seashore. Bonghwang is a traditional center of pottery and traditionally the boats anchored in the harbor were not fishing boats but trading vessels used to ship the ceramics and urns created there.

Due to its location, Bonghwang was not severely affected by the Korean War. With the arrival of peace, 30 ships a day carried the town's pottery products across the entire southern coastal region. Nowadays, however, with the country's and the economy's transformation, most master potters have left the famous town to find new jobs. There were one or two master craftsmen who stayed in the village, but many of them have by now passed away. Among all the masters and pottery experts from Bonghwang village, only Jeong Yoon-seok remains to carry on the tradition into modern times.

The village where Jeon has lived was once a thriving center for pottery and the ceramics trade. It is now simply a regular fishing village, but up until about 40 years ago its harbor had as many as 30 ships per day coming and going as the town shipped out to the world its prolific amount of pottery works.

In September 2010, the National Research Institute of Maritime Cultural Heritage hosted a reenactment of the harbor's pottery trade. The event saw many ceramic works made by Jeong Yoon-seok loaded onto traditional vessels and shipped from Gangjin to Yeosu, by way of Bonghwang.

Jeong Yoon-seok was against his son entering the traditional pottery trade upon his completion of military service. He did not want his son to walk down the same difficult life path that he had trodden. His son, however, said that it was even harder to sit by idly as such a great body of knowledge fades into extinction in his home town. So Jeong finally allowed his son to learn the trade and to become a potter.

In 2009, research began into Jeon's pottery skill and tradition and in 2010 he was awarded an official certificate that designated him as a holder of an important intangible cultural heritage ability.

*This series of article has been made possible through the cooperation of the National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. (Source: Intangible Cultural Heritage of Korea)