The year 1920 saw Korea explode. Not in war, not in violence, but in terms of media, reading and social discussion. Korea's experience of colonization, roughly February 1876 until V-J Day on Aug. 15, 1945, was oppressive and heavy, but not brutal or sadistic. A young Korean man -- for women were not allowed, of course -- could travel to Osaka or Tokyo for education, or could buy a ticket on the South Manchurian Railway (남 만주 철도 주식회사) and head north to Shenyang, Changchun or Harbin. Ethnic Koreans had at a second-tier of citizenship, along with ethnic Manchus, below the ethnic Japanese but above the ethnic Han Chinese. This allowed them to move about within the Japanese Empire, and gave the Joseon people -- for the first time -- a taste of the world. In line with this, 1920s Korea saw an explosion of literature and of the arts.

After World War I (1914-1918), the world truly changed. Empires were crumbling. There was the Irish War of Independence (January 1919) and the Egyptian revolution (1919). There was the Turkish War of Independence (May 1919). There was a new government act in India (1919). There was the May Fourth Movement in China (May 1919). Most importantly for us, in Korea there was the March First Movement that erupted onto the streets of Seoul in March 1919. Like oppressed, colonized people everywhere, Joseon was calling for sovereignty and independence, and a Korean declaration of independence was read out at the Taehwagwan Restaurant in downtown Seoul on March 1, 1919.

Up until that time in colonial Korea, there were very strict rules on what could be published. Censorship was rife. There was the Newspaper Law of 1907 and the Publication Law of 1909 that both made it difficult to get a license to print a newspaper or a magazine. Think of it like internet censorship or blocked websites, but in the early 1900s.

This stifling of intellectual thought was part of what brought the marchers onto the streets in March 1919. Now, the March First Movement didn't actually lead anywhere: not to Korean independence nor to Korean sovereignty. However, it did lead to a loosening of laws that controlled public discourse. Most importantly, and regardless of its actual results, the symbolism of the March First Movement is quite important. The imagery involved with it is often used by the modern South Korean state in its efforts to define Koreanness.

Nonetheless, in response to this fairly small, but impassioned, movement, the Japanese colonial government proclaimed a new Cultural Policy in 1920. This made it easier for anyone -- intellectuals mostly, and upper class young men with a lot of time on their hands -- to voice their opinions and to publish their voice for all and sundry to read. In 1920 alone there were 409 new permits issued for magazines, newspapers and journalists. The previous 10 years only saw 40 permits issued.

An air of optimism flourished across Seoul. Neroism was in the air. In Tokyo, Kim Dong-in -- one of our authors -- and other writers established the Korean-language magazine Creation (창조). The poetry journal Rose Village (Changmich’on) came out in 1921. The two "pure literature" magazines, White Tide (Baekcho) and Ruins (P’yehŏ), were both first published in 1920. The Korean Artists Proletarian Federation (조선 프롤레타리아 예술 가동맹) was formed in August 1925. It comprised of writers, theater workers, composers, artists and film-makers and it published a range of journals -- Cultural Construction (Munhak chanjo), Theater Movement (Yonguk undong), Battle Banner (Kungi), Collective (Chiptan) -- until the Japanese authorities forced it to disband in May 1935.

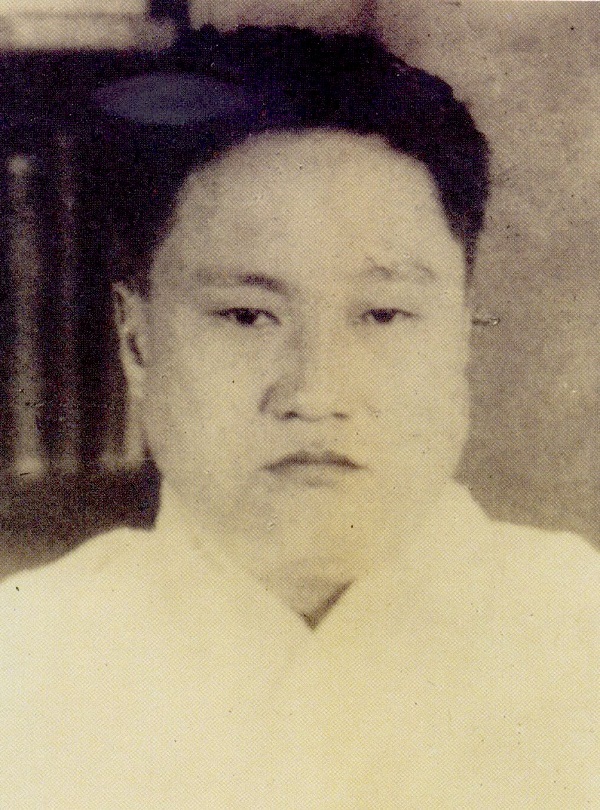

Swimming among these churning, rising tides were our two authors born in 1900: Hyun Jin-geon (1900-1943) and Kim Dong-in (1900-1951). Both in their 20s, both of their time, both riding the first wave of modern Korean literature, both are considered pioneers of modern Korean short fiction. One was born in Daegu, one in Pyongyang. Hyun Jin-geon's writings first appeared in 1920 in the pages of Genesis (개벽), a literature magazine. The other author, Kim Dong-in, first published in the pages of Creation (창조) in 1919.

Hyun's tale of an author struggling with earning an income and with reality, "Poor Man's Wife," came out in the pages of Genesis (Gaebyeok, 개벽) in 1921. Later on in this movement, in 1932, Kim's tale of self-acceptance and self-forgiveness, "Our Toes Are Alike," came out in 1932. Both short stories are almost religious, and involve a religious-like realization. They touch on what it means to be human: love and acceptance, forgiveness of others and self-forgiveness.

"Poor Man's Wife" is about the ways in which love can overcome material or physical situations. It's not stuff or belongings that makes us happy; it's the loving relationships he have, the friendships we cherish and the acceptance we receive from our community, friends and coworkers. As much as we are rational actors in the economic sense, we are also social creatures, in need of someone who truly listens.

"Our Toes Are Alike" is a touching tale of a young father coming to terms with his newlywed existence, and learning self-forgiveness for the things he has done in the past. Clocking in at only seven pages, it's one of the most concise lessons in self-forgiveness. Buddha, Jesus and Muhammad require books and books to get their message across, that self-acceptance and being able to see with eyes unclouded by hate are key to one's progress as a human being. Kim Dong-in does it in seven pages.

Both tales are good lessons for modern South Korean society, and most modern citizens of South Korea are aware of the two authors, if they haven't actually read the two short stories. (Both Hyun and Kim show up in high school textbooks.) Today's South Korea is like a grey dystopia, as opposed to the blossoming field of the 1920s and 1930s. The OECD highlights Korea for its extremely high suicide rate, its extremely high traffic fatalities, its extremely low birth rate, and its extremely low rate of female participation in the work force. Reading short stories that emphasize coming to terms with one's chosen profession, regardless of the social pressure one faces, and that emphasize knowing oneself, self-forgiveness and accepting other's for who they are, might just be a small step in the direction of healing and toward increasing people's overall happiness.

In choosing what to remember and in creating our memory, humans and societies alike have a choice between the honest truth, which is sometimes ugly, and then a sanitized, somewhat cleaner version of events. Rose tints my world, so to speak, keeps me safe from my trouble and pain. In many ways both Kim Dong-in and Hyun Jin-geon fall at the lighter end of the spectrum. They're more sanitized, even bowdlerized, ways in which modern South Korean society likes to think of itself during the 1920s and 1930s, much in the way the modern South Korean state uses the imagery of the March First Movement. Both short stories are brief windows onto the human soul, one showing how an artist can find love and acceptance, and one showing self-forgiveness and coming to terms with one's past. From among the blossoming that came forth in the 1920s and 1930s, it's no wonder these two are still read today.

Coming to terms with one's past does require a selective memory. Indeed, memory by definition is selective. Part of the duty of the modern South Korean state is to create Koreanness. By selectively going back on the peninsula's history, the many branches of the South Korean state move together -- sometimes at odds, but mostly in step -- to create this imagined community of "Korea" and to define Koreanness for the globe. This is called building a nation state, and it is expansive and open-minded enough to include citizens of North Korea and ethnic Koreans living anywhere from the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin Province through to Koreatown in Los Angeles.

So take an afternoon to read both "Poor Man's Wife" and "Our Toes Are Alike." You might learn a lesson or two about how to live to the fullest, and you'll get another bit of insight into the way in which modern South Korean society views itself.

Hyun Jin-geon's "Poor Man's Wife" was translated into English by Sora Kim-Russell in 2013, and Kim Dong-in's "Our Toes Are Alike" was translated by Stephen Epstein and Kim Mi Young even later, only in 2014. Both are put out by the LTI Korea and are available at the LTI Korea's website for free.

One final note, or perhaps this might be better as a potential Ph.D. topic: an aspiring scholar of Korean literature could do worse than to take all the back issues of Genesis, Creation and all the other literary magazines that flourished in the 1920s and 1930s and publish each and every issue electronically in modern Hangeul and then, eventually, in English. This would give the world access to the roots of modern Korean literature, for if a work doesn't exist online in English, it will fade away into the mists of time. This would also allow scholars from around the world to have access to the broad swath of first-generation modern Korean literature, greatly expanding the many choices we have when we approach Koreanness.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: LTI Korea, Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

gceaves@korea.kr

After World War I (1914-1918), the world truly changed. Empires were crumbling. There was the Irish War of Independence (January 1919) and the Egyptian revolution (1919). There was the Turkish War of Independence (May 1919). There was a new government act in India (1919). There was the May Fourth Movement in China (May 1919). Most importantly for us, in Korea there was the March First Movement that erupted onto the streets of Seoul in March 1919. Like oppressed, colonized people everywhere, Joseon was calling for sovereignty and independence, and a Korean declaration of independence was read out at the Taehwagwan Restaurant in downtown Seoul on March 1, 1919.

Up until that time in colonial Korea, there were very strict rules on what could be published. Censorship was rife. There was the Newspaper Law of 1907 and the Publication Law of 1909 that both made it difficult to get a license to print a newspaper or a magazine. Think of it like internet censorship or blocked websites, but in the early 1900s.

Hyun Jin-geon's critical comment on the life of an artist and materialism, 'Poor Man's Wife,' was published in the January 1921 issue of the literary journal Genesis (개벽). It was translated into English by Sora Kim-Russell in 2013.

Hyun Jin-geon was born in Daegu in 1900 and by the 1920s was a rising star on the Korean literary stage.

This stifling of intellectual thought was part of what brought the marchers onto the streets in March 1919. Now, the March First Movement didn't actually lead anywhere: not to Korean independence nor to Korean sovereignty. However, it did lead to a loosening of laws that controlled public discourse. Most importantly, and regardless of its actual results, the symbolism of the March First Movement is quite important. The imagery involved with it is often used by the modern South Korean state in its efforts to define Koreanness.

Nonetheless, in response to this fairly small, but impassioned, movement, the Japanese colonial government proclaimed a new Cultural Policy in 1920. This made it easier for anyone -- intellectuals mostly, and upper class young men with a lot of time on their hands -- to voice their opinions and to publish their voice for all and sundry to read. In 1920 alone there were 409 new permits issued for magazines, newspapers and journalists. The previous 10 years only saw 40 permits issued.

An air of optimism flourished across Seoul. Neroism was in the air. In Tokyo, Kim Dong-in -- one of our authors -- and other writers established the Korean-language magazine Creation (창조). The poetry journal Rose Village (Changmich’on) came out in 1921. The two "pure literature" magazines, White Tide (Baekcho) and Ruins (P’yehŏ), were both first published in 1920. The Korean Artists Proletarian Federation (조선 프롤레타리아 예술 가동맹) was formed in August 1925. It comprised of writers, theater workers, composers, artists and film-makers and it published a range of journals -- Cultural Construction (Munhak chanjo), Theater Movement (Yonguk undong), Battle Banner (Kungi), Collective (Chiptan) -- until the Japanese authorities forced it to disband in May 1935.

Swimming among these churning, rising tides were our two authors born in 1900: Hyun Jin-geon (1900-1943) and Kim Dong-in (1900-1951). Both in their 20s, both of their time, both riding the first wave of modern Korean literature, both are considered pioneers of modern Korean short fiction. One was born in Daegu, one in Pyongyang. Hyun Jin-geon's writings first appeared in 1920 in the pages of Genesis (개벽), a literature magazine. The other author, Kim Dong-in, first published in the pages of Creation (창조) in 1919.

Hyun's tale of an author struggling with earning an income and with reality, "Poor Man's Wife," came out in the pages of Genesis (Gaebyeok, 개벽) in 1921. Later on in this movement, in 1932, Kim's tale of self-acceptance and self-forgiveness, "Our Toes Are Alike," came out in 1932. Both short stories are almost religious, and involve a religious-like realization. They touch on what it means to be human: love and acceptance, forgiveness of others and self-forgiveness.

"Poor Man's Wife" is about the ways in which love can overcome material or physical situations. It's not stuff or belongings that makes us happy; it's the loving relationships he have, the friendships we cherish and the acceptance we receive from our community, friends and coworkers. As much as we are rational actors in the economic sense, we are also social creatures, in need of someone who truly listens.

"Our Toes Are Alike" is a touching tale of a young father coming to terms with his newlywed existence, and learning self-forgiveness for the things he has done in the past. Clocking in at only seven pages, it's one of the most concise lessons in self-forgiveness. Buddha, Jesus and Muhammad require books and books to get their message across, that self-acceptance and being able to see with eyes unclouded by hate are key to one's progress as a human being. Kim Dong-in does it in seven pages.

'Our Toes Are Alike,' a tale of personal growth and self forgiveness, was published by author Kim Dong-in in 1932. It was translated by Stephen Epstein and Kim Mi Young in 2014.

Kim Dong-in was born in Pyongyang in 1900 and was part of the vibrant Korean literary scene in the 1920s and 1930s.

Both tales are good lessons for modern South Korean society, and most modern citizens of South Korea are aware of the two authors, if they haven't actually read the two short stories. (Both Hyun and Kim show up in high school textbooks.) Today's South Korea is like a grey dystopia, as opposed to the blossoming field of the 1920s and 1930s. The OECD highlights Korea for its extremely high suicide rate, its extremely high traffic fatalities, its extremely low birth rate, and its extremely low rate of female participation in the work force. Reading short stories that emphasize coming to terms with one's chosen profession, regardless of the social pressure one faces, and that emphasize knowing oneself, self-forgiveness and accepting other's for who they are, might just be a small step in the direction of healing and toward increasing people's overall happiness.

| Side Note: If we can compare literature to photography, there are many photographers who truly captured life in South Korea over the past few decades. Kim Gi-chan (김기찬) is known for his nice, almost beautiful, shots that capture the myths that society wants to remember about itself, about the fierce growing pains that spat out the Miracle on the Han. His photos show the lighter side of poverty. The flip side would be Choi Min-sik (최민식) [not the actor] who captures a much more honest side of Korea, showing those fierce growing pains in gritty detail, without the selectivity of memory. His photos show the grittier side of rapid economic development. |

In choosing what to remember and in creating our memory, humans and societies alike have a choice between the honest truth, which is sometimes ugly, and then a sanitized, somewhat cleaner version of events. Rose tints my world, so to speak, keeps me safe from my trouble and pain. In many ways both Kim Dong-in and Hyun Jin-geon fall at the lighter end of the spectrum. They're more sanitized, even bowdlerized, ways in which modern South Korean society likes to think of itself during the 1920s and 1930s, much in the way the modern South Korean state uses the imagery of the March First Movement. Both short stories are brief windows onto the human soul, one showing how an artist can find love and acceptance, and one showing self-forgiveness and coming to terms with one's past. From among the blossoming that came forth in the 1920s and 1930s, it's no wonder these two are still read today.

Coming to terms with one's past does require a selective memory. Indeed, memory by definition is selective. Part of the duty of the modern South Korean state is to create Koreanness. By selectively going back on the peninsula's history, the many branches of the South Korean state move together -- sometimes at odds, but mostly in step -- to create this imagined community of "Korea" and to define Koreanness for the globe. This is called building a nation state, and it is expansive and open-minded enough to include citizens of North Korea and ethnic Koreans living anywhere from the Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture in Jilin Province through to Koreatown in Los Angeles.

So take an afternoon to read both "Poor Man's Wife" and "Our Toes Are Alike." You might learn a lesson or two about how to live to the fullest, and you'll get another bit of insight into the way in which modern South Korean society views itself.

Hyun Jin-geon's "Poor Man's Wife" was translated into English by Sora Kim-Russell in 2013, and Kim Dong-in's "Our Toes Are Alike" was translated by Stephen Epstein and Kim Mi Young even later, only in 2014. Both are put out by the LTI Korea and are available at the LTI Korea's website for free.

One final note, or perhaps this might be better as a potential Ph.D. topic: an aspiring scholar of Korean literature could do worse than to take all the back issues of Genesis, Creation and all the other literary magazines that flourished in the 1920s and 1930s and publish each and every issue electronically in modern Hangeul and then, eventually, in English. This would give the world access to the roots of modern Korean literature, for if a work doesn't exist online in English, it will fade away into the mists of time. This would also allow scholars from around the world to have access to the broad swath of first-generation modern Korean literature, greatly expanding the many choices we have when we approach Koreanness.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: LTI Korea, Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

gceaves@korea.kr

Most popular

- ROKG position on flood prevention measures along the Imjin River

- FDI Arrivals to Korea Rise 2.7% in H1 2025

- 2020 Regional Input-Output Statistics

- Authorities Introduce Measures to Strengthen Household Debt Management Centered on Seoul Metropolitan Area

- “Proprietary AI Foundation Model” Project Enters Full‑Scale Launch