The year 2014 marks the 40th anniversary of many things. It marks the 40th anniversary of Seoul’s subway system. It marks the 40th anniversary of the current president’s mother’s assassination. More importantly, however, for Korea and its culture, 2014 marks the 40th anniversary of two seminal rock albums.

In 1974, radio air time for rock’n’roll and folk music was limited. Vinyl records were expensive, but people were able to buy black market “copy” vinyl records, made from large-reel tape recorders. Enterprising merchants would buy one original vinyl music album, record it onto large reel-to-reel tapes, and thence make more, cheaper vinyl records to sell onward to the music-loving public. They broke easily, but they were cheap and most everyone was able to afford these knock-off vinyl records, giving people access to the newest and best music.

Portable record players were a bit harder to come by. These were high-tech items in the day, and only a few people had one. There were enough of them, however, for music to spread through friends and through university campuses. There were no noraebangs, or singing rooms. Those didn’t arrive until the 1980s. There were plenty of bars and music cafes, however. Bar owners were able to get inexpensive vinyl records to play for their patrons. The bars had to close at about 11:30 p.m., however, since curfew was at 12:00 a.m. midnight.

The two most popular songs in 1974 were “The Beautiful One” (“Mee-In” or “미인”), released in August 1974, and “Pass The Water, Will Ya” (“Mool Jom Joo-so” or “물 좀 주소”), released earlier in the year. They were new. They were fresh. They were fun. They weren’t overtly political, but they became so as their fans used the songs during rallies. The songs were adopted as student anthems.

The two most popular songs in 1974 were “The Beautiful One” (“Mee-In” or “미인”), released in August 1974, and “Pass The Water, Will Ya” (“Mool Jom Joo-so” or “물 좀 주소”), released earlier in the year. They were new. They were fresh. They were fun. They weren’t overtly political, but they became so as their fans used the songs during rallies. The songs were adopted as student anthems.

The first song, “The Beautiful One,” by the elder of the

two artists, was rock, funk and psychedelia. The second, “Pass The Water, Will Ya,” by the younger of the two artists, was folk, was “unplugged” and set the way for both the Korean folk scene and the Korean garage band scene. Both songs, by completely different artists, were at once liberating and controversial, violently modern and yet still quite traditional. The songs went viral, though no one would have used that term at the time. Both artists were threatened by the paranoid dictatorship, and both artists’ songs were banned from the airwaves. Together, they were two spots of light in the darkness of 1974.

“The Beautiful One” by Shin Joonghyeon is part rock and part funk, mixed with traditional Korean musical vocal styles. The artist uses his array of prior musical experiences and exposure to bring rock to his people. The opening bass line is something from Parliament or the later funk movement. Think: Bootsy Collins meets Korea. The vocals rip in with the first verse, modeling the Beatles’ vocal style on “Helter Skelter.” After four verses, Shin cascades into the chorus, with the bass walking the dog up and down the scale to his over-flying guitar riffs. Pause for a bass solo during the bridge and then back into the second verse.

In 1974, Shin Joonghyeon was 34 years old. He had been in the music industry since the Korean War (1950-1953). He had about 20 albums and singles to his name. Shin’s life story up to that point covered war, poverty, learning the guitar, emulating Elvis, being cheated by his business partners and having commercial commitments to write for other singers with no pay or credit. In the midst of all this, he was still able to form a few bands and launch numerous other singers’ careers.

Born in 1938, Shin was our first rock’n’roller. In 1955 at the age of 17 and with the war barely over, he started playing music. In 1959 he had his first guitar solo on his debut album “HiKhi-Shin: Guitar Melodies.”

In 1962, he founded Korea’s first rock band, Add 4. In 1969, he wrote and composed the complete soundtrack for the musical movie “Green Apple”, “PuReun SaGwa.”

He finally hit his stride in 1974.

August 1974 saw Shin Joonghyeon & the Coins, the newest iteration of his backup band, release their self-titled debut album “Shin Joonghyeon & the Coins” (JLS-120891) (“Shin Joonghyeon-gwa YeopJeon-deul” or “신중현과 엽전들”). It’s a psychedelic masterpiece, taking the best of ‘70s funk and tie-dyed 1968 riffs and pouring it into Korean rock, burning through the darkness of 1974.

Only about 500 copies were made in the first pressing, with a paper sleeve and a gate-like folding cover. Shin Joonghyeon played lead guitar and vocals. The Coins were Lee Namyi on bass and Kim Hosik on drums. Jimi Hendrix had a similar lineup: only one lead guitar and then a bass and drums. If you’re a good enough guitarist, you don’t need a rhythm guitar; you play both parts yourself. The first pressing was only given to radio stations. If you find one today, it’s probably the most expensive Korean vinyl out there. A CD was issued in 1994.

The second pressing (JLS-120984) had a new drummer, Kwan Youngnam and, in music style, is a little harder than the first pressing. Jigu Records wanted a slightly harder style, apparently, so the company had Shin re-make the album.

Track No. 1, “The Beautiful One,” became an instant hit amongst students and youth. In the latter half of 1974 and most of 1975, it was still being played on the radio, but was mostly enjoyed via cheaply-made vinyl records.

At the end of 1975, however, Shin was invited to the presidential mansion, the Blue House (CheongWaDae), by President Park himself. He was asked to write a song praising President Park and his political party. Shin flat out refused to meet the president.

Instead, he wrote the song “Beautiful Rivers and Mountains” (“AreumDawoon GangSan” or “아름다운 강산”) praising the beauty of the land, the beauty of nature and, of course, peace on earth.

Shin was placed under surveillance. Police officers harassed him. He was questioned about what kind of music he was writing and playing. He wasn’t allowed to hold live concerts. He was forced to have his long hair cut short. He was trailed by plain-clothes policemen.

In December 1975 he was sentenced to prison under suspicion of having used illegal drugs, in this case marijuana. He was sent to prison on December 5, 1975, tortured and then incarcerated in a mental hospital for two years. When he was released in late 1977, his songs were still banned and he had returned to a world where people listened to tepid love ballads and polkas.

His music was banned in Korea until 1987.

The second song released in the dark year of 1974 was “Pass The Water, Will Ya” (“Mool Jom Joo-so” or “물 좀 주소”), by a 26-year-old journalist working at the Korea Herald, Hahn Dae-Soo. It was track No. 1 off his first album, “The Long, Long Road” (“MeolGo Meon Gil” or “멀고 먼 길”).

If Shin’s 1974 song was more like Hendrix’s “Purple Haze”, Hahn’s 1974 song was more like Dylan’s “John Wesley Harding” album.

Hahn Dae-Soo was born in Busan and raised there and in New York City. By the time he was 26, he had just finished his military service. Before being conscripted, he had played at Korean universities in 1968 and 1969. Finishing his navy duty, however, he got a job as a journalist and came out with his first solo album, “The Long, Long Road.”

His songs were about seeking freedom, the wish to be happy and the poor life of the common man. He played the acoustic guitar himself. His songs were instantly popular.

Track No. 1 was “Pass The Water, Will Ya,” a man crying in the dehydrated pain of a hangover for a glass of water. Desperation, seeking something revitalizing, was the message: a populace gasping for air, clutching at water in the desert.

Hahn’s growly voice rips open the song to a guitar rhythm from Sonny & Cher or from Mama & The Papas. The bass slides up and down as he continues to howl about how desperate life is and what we need to survive: pass the water, please. The drums are merely Ringo, but that’s enough to carry the song. It’s an instant anthem. During the bridges, Hahn’s howls resemble Lennon and Ono’s scream therapy. Even the album cover has him in beautiful pain: he’s grabbing his face close up, in despair and disgust.

“The Long, Long Road” album and his subsequent “Rubber Shoes” (1975) (“GoMoo Shin” or “고무신”) album were enough, in President Park’s eyes, to get the music banned. Hahn’s music was verboten until the late 1980s. Hahn moved more or less permanently to New York City. He formed a band and, to this author’s knowledge, is the only Korean rock star to ever have performed at CBGB’s, the famous New York rock club during the 1970s.

In Korea, music deemed to be “inappropriate” was banned by the government. In fact, the dictator’s sole fear was the students, and the students loved Hahn Dae-Soo.

Student demonstrators, marching for democracy, marching for civil liberties and marching for freedom of speech, would sing Hahn Dae-Soo songs at their rallies. Hahn’s songs drew patriotic support. They were sung like anthems. College students wanted democracy and they wanted it now. Students would gather together in a mass rally, sing the songs, and tie themselves together at the shoulder so that they wouldn’t break when charged at by the riot police; riot police with shields, batons and helmets. They wanted justice and democracy.

“Pass The Water, Will Ya” (“Mool Jom Joo-so” or “물 좀 주소”) was ostensibly just about a poor guy suffering from a hangover. However, it was sung as a cry for freedom by the people in the streets, for release from this prison. Also, it was tauntingly sung by students in reference to the government’s policy of using water torture on student and democracy activists.

Hahn’s most beautiful song, “To A Happy Land” (“Haengbok-eh Nara-ro” or 행복의 나라로”), a guitarry folk song, wishes for a world and a country where there are no black curtains and where no darkness exists.

Today, forty years later, Hahn Dae-Soo’s official homepage is called the “Land of Happiness.”

Today’s Korea is eons away from 1974. Politically, socially and culturally, we are in a different world. Korean culture and music, too, has developed in leaps and bounds. Nowadays, Korea takes global pop culture, makes it its own and re-exports it.

Today’s Korea is eons away from 1974. Politically, socially and culturally, we are in a different world. Korean culture and music, too, has developed in leaps and bounds. Nowadays, Korea takes global pop culture, makes it its own and re-exports it.

According to a recent study (Yoon, 2005), U.S. cultural products account for 75% of Korea’s audiovisual imports. On the opposite side, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and mainland China account for 82.3% of Korea’s audiovisual exports. Korea takes in from the West, “Asia-fies” it and re-exports it to the East. Such vibrancy is only possible in a free democracy, where culture can bloom.

Walking through the underground shopping arcade between Myeongdong and the Shinsaegye Department Store, there’s one—and only one—vinyl record store. It’s the size of a closet, run by a very quiet man, perhaps mute, with a long ponytail. He has Shin Joonghyeon and Hahn Dae-Soo vinyl records, amongst many, many other artists.

You can buy a vinyl record of Hahn Dae-Soo’s “The Long, Long Road,” carefully wrapped in preservative plastic and with no or very few scratches, for 110,000 won.

In today’s Korea, forty years later, you can listen to it anytime you want.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korean.net Staff Writer

gceaves@korea.kr

In 1974, radio air time for rock’n’roll and folk music was limited. Vinyl records were expensive, but people were able to buy black market “copy” vinyl records, made from large-reel tape recorders. Enterprising merchants would buy one original vinyl music album, record it onto large reel-to-reel tapes, and thence make more, cheaper vinyl records to sell onward to the music-loving public. They broke easily, but they were cheap and most everyone was able to afford these knock-off vinyl records, giving people access to the newest and best music.

Portable record players were a bit harder to come by. These were high-tech items in the day, and only a few people had one. There were enough of them, however, for music to spread through friends and through university campuses. There were no noraebangs, or singing rooms. Those didn’t arrive until the 1980s. There were plenty of bars and music cafes, however. Bar owners were able to get inexpensive vinyl records to play for their patrons. The bars had to close at about 11:30 p.m., however, since curfew was at 12:00 a.m. midnight.

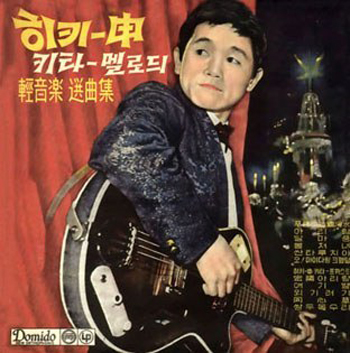

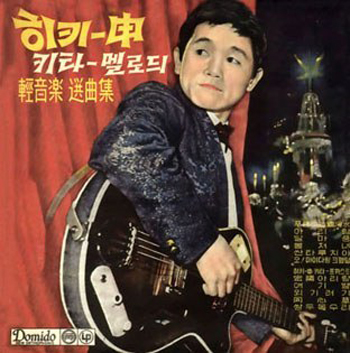

“HiKhi-Shin: Guitar Melodies” (1959) was Sin Joonghyun’s first album. (photo courtesy of Daum Music)

The first song, “The Beautiful One,” by the elder of the

two artists, was rock, funk and psychedelia. The second, “Pass The Water, Will Ya,” by the younger of the two artists, was folk, was “unplugged” and set the way for both the Korean folk scene and the Korean garage band scene. Both songs, by completely different artists, were at once liberating and controversial, violently modern and yet still quite traditional. The songs went viral, though no one would have used that term at the time. Both artists were threatened by the paranoid dictatorship, and both artists’ songs were banned from the airwaves. Together, they were two spots of light in the darkness of 1974.

“The Beautiful One” by Shin Joonghyeon is part rock and part funk, mixed with traditional Korean musical vocal styles. The artist uses his array of prior musical experiences and exposure to bring rock to his people. The opening bass line is something from Parliament or the later funk movement. Think: Bootsy Collins meets Korea. The vocals rip in with the first verse, modeling the Beatles’ vocal style on “Helter Skelter.” After four verses, Shin cascades into the chorus, with the bass walking the dog up and down the scale to his over-flying guitar riffs. Pause for a bass solo during the bridge and then back into the second verse.

In 1974, Shin Joonghyeon was 34 years old. He had been in the music industry since the Korean War (1950-1953). He had about 20 albums and singles to his name. Shin’s life story up to that point covered war, poverty, learning the guitar, emulating Elvis, being cheated by his business partners and having commercial commitments to write for other singers with no pay or credit. In the midst of all this, he was still able to form a few bands and launch numerous other singers’ careers.

Born in 1938, Shin was our first rock’n’roller. In 1955 at the age of 17 and with the war barely over, he started playing music. In 1959 he had his first guitar solo on his debut album “HiKhi-Shin: Guitar Melodies.”

In 1962, he founded Korea’s first rock band, Add 4. In 1969, he wrote and composed the complete soundtrack for the musical movie “Green Apple”, “PuReun SaGwa.”

He finally hit his stride in 1974.

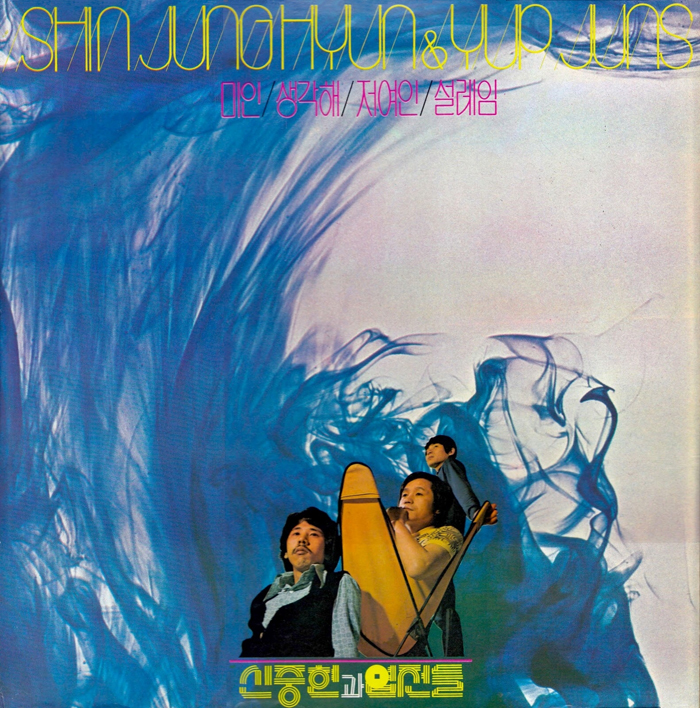

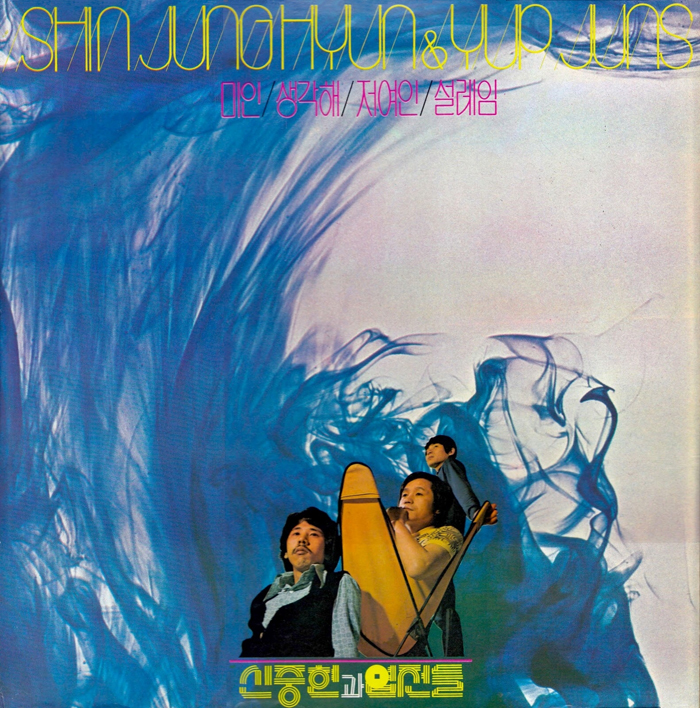

August 1974 saw Shin Joonghyeon & the Coins, the newest iteration of his backup band, release their self-titled debut album “Shin Joonghyeon & the Coins” (JLS-120891) (“Shin Joonghyeon-gwa YeopJeon-deul” or “신중현과 엽전들”). It’s a psychedelic masterpiece, taking the best of ‘70s funk and tie-dyed 1968 riffs and pouring it into Korean rock, burning through the darkness of 1974.

Only about 500 copies were made in the first pressing, with a paper sleeve and a gate-like folding cover. Shin Joonghyeon played lead guitar and vocals. The Coins were Lee Namyi on bass and Kim Hosik on drums. Jimi Hendrix had a similar lineup: only one lead guitar and then a bass and drums. If you’re a good enough guitarist, you don’t need a rhythm guitar; you play both parts yourself. The first pressing was only given to radio stations. If you find one today, it’s probably the most expensive Korean vinyl out there. A CD was issued in 1994.

The second pressing (JLS-120984) had a new drummer, Kwan Youngnam and, in music style, is a little harder than the first pressing. Jigu Records wanted a slightly harder style, apparently, so the company had Shin re-make the album.

Jigu Records released Shin Joonghyeon’s twentieth album on August 25, 1974, “Shin Joonghyeon & the Coins” (JLS-120891) (“신중현과 엽전들”). Track No. 1 is “The Beautiful One” (“미인”). (photo courtesy of Daum Music)

Track No. 1, “The Beautiful One,” became an instant hit amongst students and youth. In the latter half of 1974 and most of 1975, it was still being played on the radio, but was mostly enjoyed via cheaply-made vinyl records.

At the end of 1975, however, Shin was invited to the presidential mansion, the Blue House (CheongWaDae), by President Park himself. He was asked to write a song praising President Park and his political party. Shin flat out refused to meet the president.

Instead, he wrote the song “Beautiful Rivers and Mountains” (“AreumDawoon GangSan” or “아름다운 강산”) praising the beauty of the land, the beauty of nature and, of course, peace on earth.

Shin was placed under surveillance. Police officers harassed him. He was questioned about what kind of music he was writing and playing. He wasn’t allowed to hold live concerts. He was forced to have his long hair cut short. He was trailed by plain-clothes policemen.

In December 1975 he was sentenced to prison under suspicion of having used illegal drugs, in this case marijuana. He was sent to prison on December 5, 1975, tortured and then incarcerated in a mental hospital for two years. When he was released in late 1977, his songs were still banned and he had returned to a world where people listened to tepid love ballads and polkas.

His music was banned in Korea until 1987.

Shin Joonghyen and The Coins perform in 1974. From left are bassist Lee Namyi, drummer Kim Hoshik and lead guitarist and vocalist Shin Joonghyeon. (photo courtesy of Bing Images)

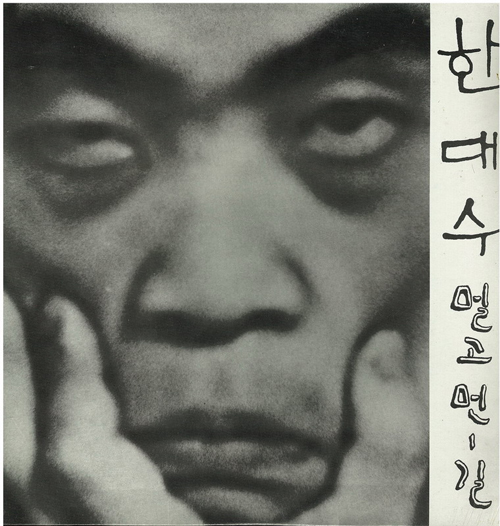

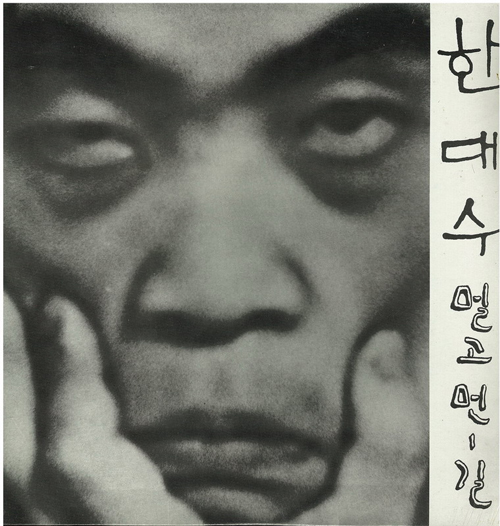

The second song released in the dark year of 1974 was “Pass The Water, Will Ya” (“Mool Jom Joo-so” or “물 좀 주소”), by a 26-year-old journalist working at the Korea Herald, Hahn Dae-Soo. It was track No. 1 off his first album, “The Long, Long Road” (“MeolGo Meon Gil” or “멀고 먼 길”).

If Shin’s 1974 song was more like Hendrix’s “Purple Haze”, Hahn’s 1974 song was more like Dylan’s “John Wesley Harding” album.

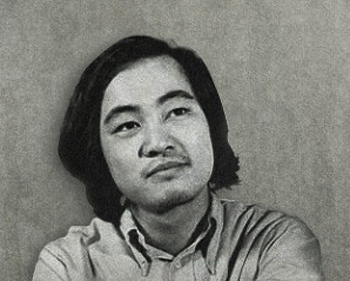

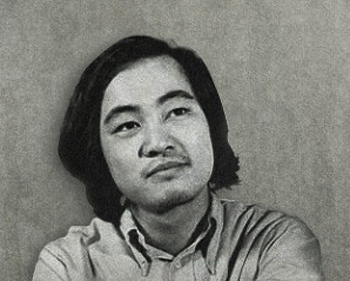

Hahn Dae-Soo was born in Busan and raised there and in New York City. By the time he was 26, he had just finished his military service. Before being conscripted, he had played at Korean universities in 1968 and 1969. Finishing his navy duty, however, he got a job as a journalist and came out with his first solo album, “The Long, Long Road.”

His songs were about seeking freedom, the wish to be happy and the poor life of the common man. He played the acoustic guitar himself. His songs were instantly popular.

Track No. 1 was “Pass The Water, Will Ya,” a man crying in the dehydrated pain of a hangover for a glass of water. Desperation, seeking something revitalizing, was the message: a populace gasping for air, clutching at water in the desert.

Hahn’s growly voice rips open the song to a guitar rhythm from Sonny & Cher or from Mama & The Papas. The bass slides up and down as he continues to howl about how desperate life is and what we need to survive: pass the water, please. The drums are merely Ringo, but that’s enough to carry the song. It’s an instant anthem. During the bridges, Hahn’s howls resemble Lennon and Ono’s scream therapy. Even the album cover has him in beautiful pain: he’s grabbing his face close up, in despair and disgust.

Hahn’s “The Long, Long Road” came out in 1974. It was banned until the late 1980s. (photo courtesy of Daum Music)

“The Long, Long Road” album and his subsequent “Rubber Shoes” (1975) (“GoMoo Shin” or “고무신”) album were enough, in President Park’s eyes, to get the music banned. Hahn’s music was verboten until the late 1980s. Hahn moved more or less permanently to New York City. He formed a band and, to this author’s knowledge, is the only Korean rock star to ever have performed at CBGB’s, the famous New York rock club during the 1970s.

In Korea, music deemed to be “inappropriate” was banned by the government. In fact, the dictator’s sole fear was the students, and the students loved Hahn Dae-Soo.

Student demonstrators, marching for democracy, marching for civil liberties and marching for freedom of speech, would sing Hahn Dae-Soo songs at their rallies. Hahn’s songs drew patriotic support. They were sung like anthems. College students wanted democracy and they wanted it now. Students would gather together in a mass rally, sing the songs, and tie themselves together at the shoulder so that they wouldn’t break when charged at by the riot police; riot police with shields, batons and helmets. They wanted justice and democracy.

“Pass The Water, Will Ya” (“Mool Jom Joo-so” or “물 좀 주소”) was ostensibly just about a poor guy suffering from a hangover. However, it was sung as a cry for freedom by the people in the streets, for release from this prison. Also, it was tauntingly sung by students in reference to the government’s policy of using water torture on student and democracy activists.

Hahn’s most beautiful song, “To A Happy Land” (“Haengbok-eh Nara-ro” or 행복의 나라로”), a guitarry folk song, wishes for a world and a country where there are no black curtains and where no darkness exists.

Today, forty years later, Hahn Dae-Soo’s official homepage is called the “Land of Happiness.”

A 26-year-old Hahn Dae-soo released his first album in 1974. (photo courtesy of Daum Music)

According to a recent study (Yoon, 2005), U.S. cultural products account for 75% of Korea’s audiovisual imports. On the opposite side, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore and mainland China account for 82.3% of Korea’s audiovisual exports. Korea takes in from the West, “Asia-fies” it and re-exports it to the East. Such vibrancy is only possible in a free democracy, where culture can bloom.

Walking through the underground shopping arcade between Myeongdong and the Shinsaegye Department Store, there’s one—and only one—vinyl record store. It’s the size of a closet, run by a very quiet man, perhaps mute, with a long ponytail. He has Shin Joonghyeon and Hahn Dae-Soo vinyl records, amongst many, many other artists.

You can buy a vinyl record of Hahn Dae-Soo’s “The Long, Long Road,” carefully wrapped in preservative plastic and with no or very few scratches, for 110,000 won.

In today’s Korea, forty years later, you can listen to it anytime you want.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korean.net Staff Writer

gceaves@korea.kr