"Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?" (1989)

Directed by Bae Yong-kyun

Comments by Kang Seong-ryul, film critic and professor at Kwangwoon University

At a certain point in my life, I watched this movie again and again. Sometimes I turned this movie on before I went to sleep. I liked this movie that much. I've almost memorized all the dialogue. I was particularly impressed by the dignified speech and dialogue of Hyegok. His words opened my eyes to the vanity of life and to the teachings of Zen Buddhism that help us to overcome such vanity.

In the opening of the film appears a phrase that reads, "He holds up a flower to show it to his disciples who ask the truth." It is the so-called yeom-hwa-mi-so, or 拈華微笑, a Buddhist term referring to wordless communication. Director Bae holds up this movie for the public to see, and then, what are we supposed to learn from it?

The movie is about Director Bae's personal life. The whole movie consists of questions and answers, the questions of Hyegok and the answers of Kibong. The director placed into the film his knowledge of Zen Buddhism and his own views of the world.

In the first part of the movie, Hyegok has a monologue that begins, "The beginning and the end are the same. We can never be born and never die."

At that moment, a toad appears, crawling slowly. It is a visual comparison with the lives of people, always crawling for some vain hope.

The questions posed by Zen Buddhist priests are priceless. The movie opens people's eyes to the vanity of life. If the movie is translated into other languages, some features may be immediately lost. Translating Buddhist terminologies into day-to-day phrases in foreign languages cannot be done as an exact translation, but must use some paraphrasing.

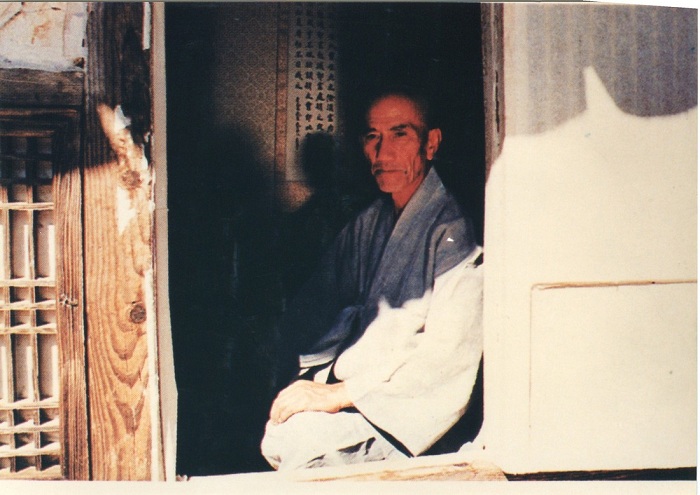

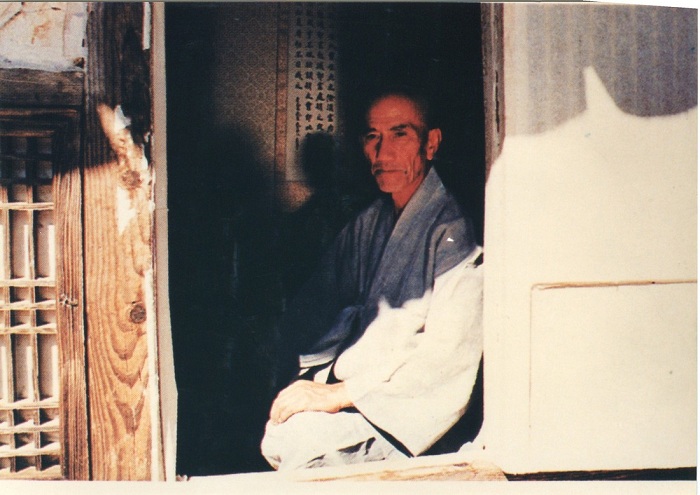

This film is about the stories of three monks. The Zen Buddhist priest Hyegok immerses himself in the teachings of Buddha, while preparing for his death, as he is old. Kibong, a younger monk, passionately listens to his teachings. Haejin, the youngest, is curious about everything in the world.

The main conflict throughout the film is the inner conflict experienced by Kibong. He can never set himself free from anxiety surrounding Ang-sa-bu-mo, or 仰事父母, the violation of moral laws within the family relationship. On the flip side, Kibong wants to pursue Gyeon-seong-seong-bul, or 見性成佛, the devotion of himself to learning the teachings of Buddha and to reaching a spiritual plain. He stands in between the spiritual and the physical world. Hyegok tells him that all the agony and all the disillusions are key tools to helping him find his true self.

Kibong suffers from inner conflicts several more times, about whether to leave the mountain temple or not, as he undergoes his training. He thinks about leaving the temple after he sees his mother. However, he decides to dedicate himself to attaining a higher level of self-discipline in order to let go of such ideas. Finally, he reaches enlightenment.

Meanwhile, in the final scene of the movie, Haejin casts out the bird that used to continually bother him. It flies away into the sky. Then, by burning all of Hyegok's possessions, Haejin is also freed from his obsession with the material and the humane.

The movie is about life and death. Haejin, a young monk, dies in this earthly world, and continues to live in the mountains. He experiences death when he falls into the water because of the bird and due to being tricked by other kids. He then witnesses Hyegok's death, experiencing death once again. Kibong thinks he killed himself when he came to the mountain. He can never desert himself, the earthly Kibong. However, he happens to experience death, too, when he falls into a deep river while carrying out some self-discipline techniques. He finally meets his true self when he witnesses the death of his teacher. The movie depicts the detailed course of how religion deals with life and death.

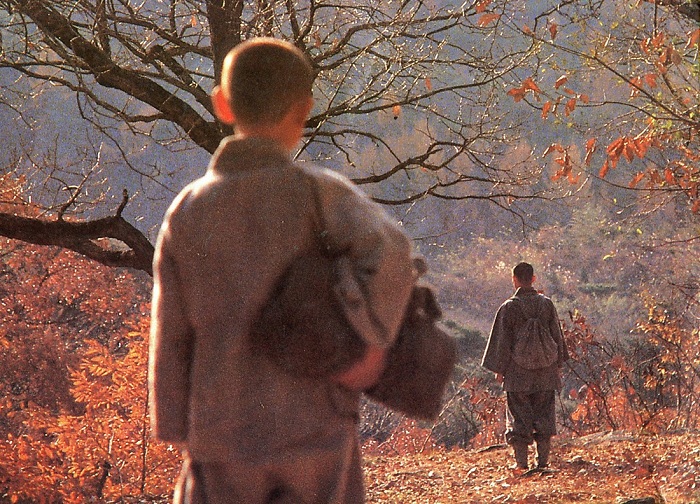

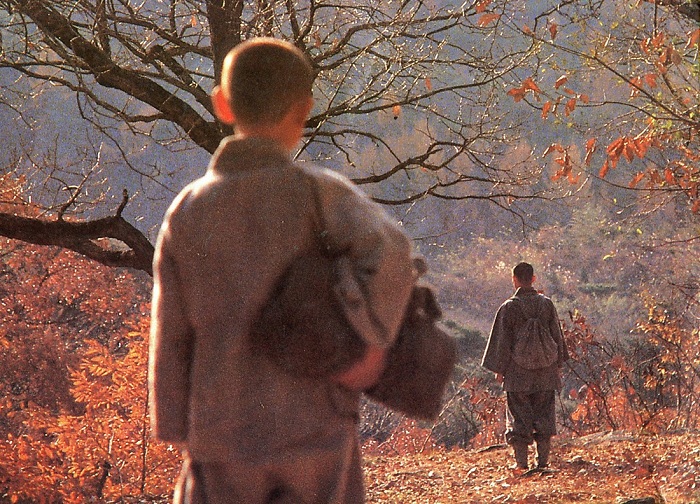

The movie uses an angle that allows a peek into East Asian philosophy. In one scene, where two monks are in training, they are shown as existing with the nature that surrounds them. The sound of the wind and the chirping of the insects plays an important role, too.

The director, an art major, portrays Kibong as having a very dark background, as he is entrapped by dark clouds. Thanks to this effect, his agony looms large on screen.

The movie breaks boundaries between Realism and Expressionism. The movie shows the director's views on seeking the truth.

The editing is amazing. When the movie was made, editing technology wasn't really that good. Nonetheless, Kibong's past, present and future are all connected in a very natural way. The stories of Hyegok, Haejin and Kibong are all well edited, without any jarring breaks. Time isn't important here. Neither is space. The important thing is that the movie is perfect in telling what it wants to tell.

After watching this movie, "Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?" almost every other film seems smaller, like dirt. This is a precious example of the way in which a movie, a medium that originated in the West, can become a new medium to introduce Buddhist ideas and concepts to a wider audience, and, furthermore, which can be introduced back into the culture from which it came.

I predict that we will never see a movie like "Why Has Bodhi-Dhama Left for the East?" again in the history of Korean cinema. I see it as a miracle.

* This series of articles has been made possible by the cooperation of the Korean Film Archive.

*Click here to see previous parts in our series about Korea.net's must-see films

Directed by Bae Yong-kyun

Deep in the mountains there is a temple where two monks -- Hyegok, an old Zen master, and Haejin, an orphan boy -- live together. One day, a new young monk, Kibong, visits the temple. As he finds himself unable to resist the earthly world, Kibong wants to be taught by Hyegok. Kibong and Hyegok share a spiritual communion. Kibong is continuously exposed to penance and self-mortification, but he can't set himself free from the inner conflicts and his earthly desires.

Hyegok knows that he is old enough to prepare for his death. He asks Kibong to cremate his body in secret, and Kibong does so. When it is all done, Kibong passes on what Hyegok left to Haejin and leaves the temple. Haejin asks him where to go. Without a word, Kibong looks up to the sky. The night comes, and Haejin is left alone in the temple. Haejin makes a fire in the furnace and burns all of Hyegok's keepsakes.

Comments by Kang Seong-ryul, film critic and professor at Kwangwoon University

At a certain point in my life, I watched this movie again and again. Sometimes I turned this movie on before I went to sleep. I liked this movie that much. I've almost memorized all the dialogue. I was particularly impressed by the dignified speech and dialogue of Hyegok. His words opened my eyes to the vanity of life and to the teachings of Zen Buddhism that help us to overcome such vanity.

In the opening of the film appears a phrase that reads, "He holds up a flower to show it to his disciples who ask the truth." It is the so-called yeom-hwa-mi-so, or 拈華微笑, a Buddhist term referring to wordless communication. Director Bae holds up this movie for the public to see, and then, what are we supposed to learn from it?

The movie is about Director Bae's personal life. The whole movie consists of questions and answers, the questions of Hyegok and the answers of Kibong. The director placed into the film his knowledge of Zen Buddhism and his own views of the world.

In the first part of the movie, Hyegok has a monologue that begins, "The beginning and the end are the same. We can never be born and never die."

At that moment, a toad appears, crawling slowly. It is a visual comparison with the lives of people, always crawling for some vain hope.

The questions posed by Zen Buddhist priests are priceless. The movie opens people's eyes to the vanity of life. If the movie is translated into other languages, some features may be immediately lost. Translating Buddhist terminologies into day-to-day phrases in foreign languages cannot be done as an exact translation, but must use some paraphrasing.

This film is about the stories of three monks. The Zen Buddhist priest Hyegok immerses himself in the teachings of Buddha, while preparing for his death, as he is old. Kibong, a younger monk, passionately listens to his teachings. Haejin, the youngest, is curious about everything in the world.

The main conflict throughout the film is the inner conflict experienced by Kibong. He can never set himself free from anxiety surrounding Ang-sa-bu-mo, or 仰事父母, the violation of moral laws within the family relationship. On the flip side, Kibong wants to pursue Gyeon-seong-seong-bul, or 見性成佛, the devotion of himself to learning the teachings of Buddha and to reaching a spiritual plain. He stands in between the spiritual and the physical world. Hyegok tells him that all the agony and all the disillusions are key tools to helping him find his true self.

Kibong suffers from inner conflicts several more times, about whether to leave the mountain temple or not, as he undergoes his training. He thinks about leaving the temple after he sees his mother. However, he decides to dedicate himself to attaining a higher level of self-discipline in order to let go of such ideas. Finally, he reaches enlightenment.

Meanwhile, in the final scene of the movie, Haejin casts out the bird that used to continually bother him. It flies away into the sky. Then, by burning all of Hyegok's possessions, Haejin is also freed from his obsession with the material and the humane.

The movie is about life and death. Haejin, a young monk, dies in this earthly world, and continues to live in the mountains. He experiences death when he falls into the water because of the bird and due to being tricked by other kids. He then witnesses Hyegok's death, experiencing death once again. Kibong thinks he killed himself when he came to the mountain. He can never desert himself, the earthly Kibong. However, he happens to experience death, too, when he falls into a deep river while carrying out some self-discipline techniques. He finally meets his true self when he witnesses the death of his teacher. The movie depicts the detailed course of how religion deals with life and death.

The movie uses an angle that allows a peek into East Asian philosophy. In one scene, where two monks are in training, they are shown as existing with the nature that surrounds them. The sound of the wind and the chirping of the insects plays an important role, too.

The director, an art major, portrays Kibong as having a very dark background, as he is entrapped by dark clouds. Thanks to this effect, his agony looms large on screen.

The movie breaks boundaries between Realism and Expressionism. The movie shows the director's views on seeking the truth.

The editing is amazing. When the movie was made, editing technology wasn't really that good. Nonetheless, Kibong's past, present and future are all connected in a very natural way. The stories of Hyegok, Haejin and Kibong are all well edited, without any jarring breaks. Time isn't important here. Neither is space. The important thing is that the movie is perfect in telling what it wants to tell.

After watching this movie, "Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East?" almost every other film seems smaller, like dirt. This is a precious example of the way in which a movie, a medium that originated in the West, can become a new medium to introduce Buddhist ideas and concepts to a wider audience, and, furthermore, which can be introduced back into the culture from which it came.

I predict that we will never see a movie like "Why Has Bodhi-Dhama Left for the East?" again in the history of Korean cinema. I see it as a miracle.

* This series of articles has been made possible by the cooperation of the Korean Film Archive.

*Click here to see previous parts in our series about Korea.net's must-see films