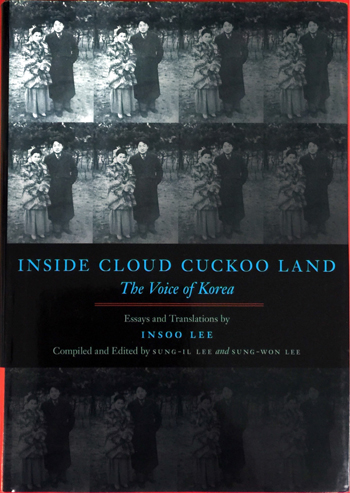

'Inside Cloud Cuckoo Land - The Voice of Korea' by Lee Insoo

Manuscripts containing the thoughts and soul of a deceased father were retrieved from a family's long-cherished possessions and have been published as a book.

"Inside Cloud Cuckoo Land - The Voice of Korea" can be divided into two parts. The first consists of Lee Insoo's (1916-1950) essays and dialogue with readers from the time he worked at Korea's first English-language daily, the Seoul Times. The second part is composed of poetry and short story translations.

In his first essay of the 25 included in the book, "Aesthetic Achievements of Korea: A Historical Survey of Classic Art," he explains why Korean art is unique and different from that of China or Japan.

He wrote "If Chinese art may be said to excel in solidity of form, and Japanese in delight of color, Korean art must be said to stand for the capture of the fleeting moment in line." He said the reason for this is that Korea was a peninsula, neither a continent nor an island chain.

Another essay, "Plea for a Moral Education," contains remarks like, "What Korea needs today is a prophetic genius who will hold the nation in his confidence, rather than a political leader pure and simple who likes the game of power-politics for its thrilling adventure." In the end, he brings attention to two points particularly overlooked during his times.

First, human decency should become the foremost value. As an example, he calls for traits like being healthy-minded, raising serviceable youth, having men and women who will work better in a team, better than their predecessors, being more open-minded and less bigoted, being more tenacious and less sentimental and encouraging people to learn to acquiesce to the decision of the majority.

Second, he says, "We should take more pains to inculcate the true spirit of freedom." Quoting Earl Baldwin, he says that there is no harder task than these words: "We have to remember that the price of liberty is eternal vigilance, and I may add, eternal knowledge, eternal sympathy and eternal understanding."

Other essays in the book include "Democracy in the Orient: From a Non-Political Point of View", "Moral Burden of the Aid Agreement", "Military Training at Schools" and more, where he captures the various historical, philosophical and ideological standpoints that society encountered during his times: post-liberation (1945) to just before the Korean War (1950-1953) broke out.

In his exchanges with numerous readers that accompany the essays, his strong sense of neutrality seeps through.

One example is from "The Students' National Guard: Its Purpose and Function." A reader wrote that the purpose of the article was unclear -- praise or condemn? -- and that it was merely a pointless repetition of the education minister's point of view.

He also questioned how one could judge a program without suggesting any criteria, and that a Gallup poll should have been set up for teachers and students to garner public opinion.

In response, Lee answered, "First, I meant exactly what I said, with full documentary grounds for saying it. Second, your argument definitely begs for the indictment of 'communist complaints.' Third, there is nothing good or bad, but thinking makes it so. This applies as much to theatrical claptraps as to genuine statecraft. Fourth, it is not my business to deal our judgments, which rests solely in the hand of the Minister himself, but to merely to report. Fifth, Gallup polls are unreliable things. Think of the last presidential election case in the U.S. Why should we in Korea bother about such futile setups?"

The poetry selections include Han Yong-un's "Mountain Abode", Kim So-wol's "Wild Flowers From the Mountains" and "Sak-ju-ku-song," Yi Sang-hwa's "Does Spring Come to These Ravished Fields?," Chong Ji-yong's "In the Glen of Ku-song-dong" and "Stars," Yi Yuk-sa's "The Vertex" and Kim Ki-rim's "The Fountain." This selection of literature translations shows Lee's lyrical taste.

In the Glen of Ku-song-dong (九城洞)

by Chong Ji-yong (1902-1950)

Often in the glen

Are buried shooting stars.

Where at dusk at times

Noisy showers of hail accumulate,

Where the very flowers

Live in exile,

With no wind tarrying

Where once an ancient temple stood,

In the dim mountain shadow

A stag is seen to move over the ridge.

Lee Insoo was born in Gurye, Jeollanam-do, in 1916. He had an advanced education in commerce, yet due to a passion for literary studies he left to study in England. While at the University of London he passed the Intermediate Examination for Internal Students in English, Latin, French and German. He finally graduated with a bachelor's degree in English language and literature. Returning home, he served as an English instructor at Posong College in 1945, where he became an associate professor at what is now Korea University. He stayed there until interrupted by the start of the Korean War. At the same time, he was the editor of the Seoul Times.

After the war started on June 25, 1950, he was taken by the North Korean army and was forced to interpret interrogations of U.S. servicemen in custody. He also had to participate in English radio propaganda for the communist cause. In September of the same year, he surrendered to U.N. forces who had taken back Seoul, yet was handed over to the Korean army only to be sentenced to death during a court martial and executed in November.

The author's children claim that they have come to terms with their feelings by publishing this volume that includes the many thoughts of their short-lived father's work.

The book is available here.

By Paik Hyun

Korea.net Staff Writer

cathy@korea.kr

Book provided and recommended by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea.