- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

Last Sunday, I visited the old Sungkyunkwan campus to pay my respects to Confucius and his disciples. I showed up with a diverse group of people from the Royal Asiatic Society, the world's oldest Korean studies group, to attend the Seokjeon Daeje, which consists of a ritual sacrifice and a mass performance that typically lasts around two hours.

The name Seokjeon comes from the two Chinese characters, 釋 (to lay out) and 酋 (alcohol), the latter which is supposed to resemble a glass of alcohol on a table. Literally translated, the name means "Laying out offerings ceremony."

Here's looking at you, Confucius!

This performance was once common across all Confucianist nations of East Asia, but due to China's 20th-century political history, Korea is the last remaining place where this spectacular tradition is maintained. Seokjeon Daeje is held twice a year, commemorating Confucius' birthday in fall, and the anniversary of his death in early spring. The ceremony is performed in Confucian academies known as hyanggyo across the nation, but the biggest and grandest ceremony is performed at Sungkyunkwan, Korea's oldest institute of higher education.

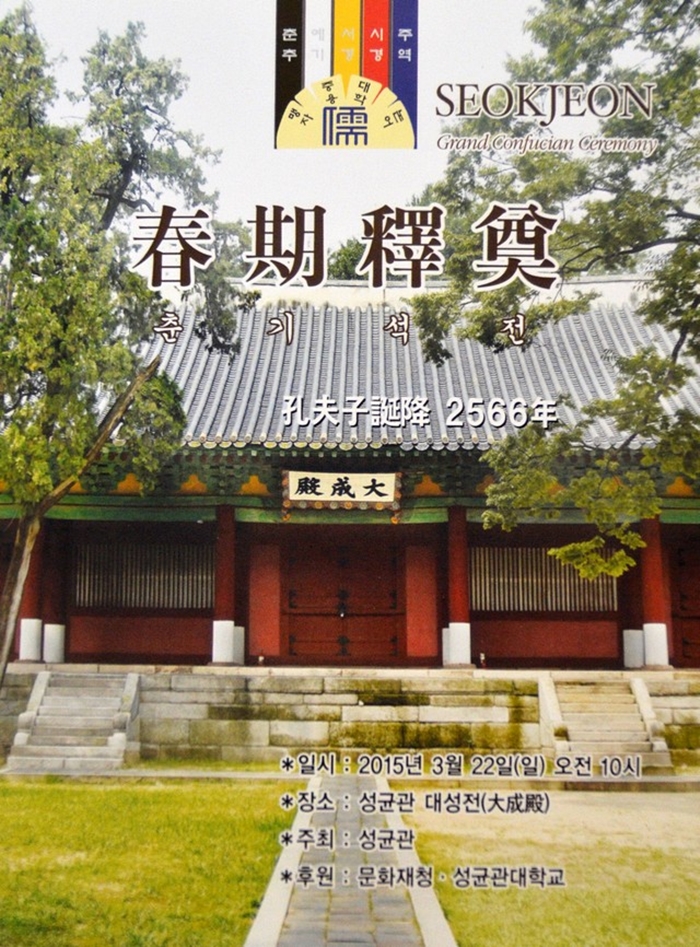

Sungkyunkwan has historically served two functions, as I wrote about before: it educated the Joseon Dynasty's future politicians and philosophers, and it is the site of Korea's (and currently the world's) most important shrine to Confucius. Students at Sungkyunkwan studied Confucius' teachings on full royal scholarship, and they also participated in Confucian ancestral worship rites that were attended by the king. It might surprise you that Sungkyunkwan is home to a fully active Confucian temple known as Munmyo, which houses a shrine to Confucius known as Daeseongjeon, or "Hall of Great Achievement."

When we arrived at Sungkyunkwan's historic campus at 10am, the grounds of Munmyo were filled with dancers, musicians, officiants, and spectators. All of the gates were open, and there were volunteers to hand out booklets, collect visitors' signatures, and prevent you from walking where you shouldn't.

Daeseongjeon lies open across Yeongshin, the spirit path.

The opened gates are highly relevant, as many of them are only opened for special events such as Seokjeonje. Immediately behind me is Sinsammun, literally "Spirit Three Gate." It gets its name from its three separate entrances, similar to how royal palaces have a central entrance intended only for the king. But here in Munmyo, even the king could not enter through the central opening: it was reserved only for the spirits of Confucius and his disciples, who were held in higher regard in Joseon than even the ruling kings.

To prevent guests from committing the faux pas of entering through Confucius' own private entrance, volunteers are deployed.

Volunteers stand guard over the central door of Sinsammun, as seen from inside.

Once the spirits enter, they follow the central path up toward Daeseongjeon, and it likewise is a major faux pas to cross this path, especially during a ceremony when the gates are open.

They are keeping an eye on me to make sure I don't try something stupid.

The ceremony started with a national ceremony, and then began the ceremonial sacrifice, accompanied by a mass performance of 64 dancers and 64 musicians. Why 64? Well, if eight is a lucky number in East Asian culture, then its square, 64, is that much luckier, essentially.

An 8X8 grid of red-clad dancers performed for the entire two hours of the ceremony, moving slowly, gracefully, and solemnly.

The Munmyo Ilmu is performed by 64 dancers and 64 musicians.

In this dance, they raise their arms up to the heavens, directing a welcoming gesture down to the earth. The steps are performed in the four cardinal directions: north, south, east, and west. During the performance, they alternate between two hats representing scholar and warrior, and they hold many different tools in their hands throughout.

The shape of these implements should make their function apparent.

The slow, deliberate moves of the dance may look simple, but I defy you to move gracefully on bent knees after two hours, let alone in sync with 63 other dancers.

The music accompanying their slow, deliberate dance moves is similarly slow, eerie, and otherworldly, punctuated by flat notes by striking a bell, which are maintained for several seconds before raising sharply at the end with the help of wood flutes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZPWU1xYELEU

(note: video is not mine, and is from a previous ceremony)

The instruments themselves are quite remarkable. There are the stone chimes known as gyeong, which may be suspended in an array called pyeongyeong, or hanging alone in a teukgyeong.

The pyeongyeong is performed by being struck by a mallet.

Similarly, there are instruments using bronze bells, known as jong in Korean. They may either be in an array as pyeonjong or hanging alone as teukjong.

Here's a pyeonjong in the SKKU Museum.

Percussion is provided by the large nogo or the smaller nodo. Both have tigers for feet, and the nodo has a bird on top.

The nodo is played by a drummer.

One of the most striking instruments (sorry for the pun) is the simply named eo, which is in the shape of a tiger with a spiny back. It is played by scraping a bamboo stick along the spine, creating a ratcheting sound similar to a Latin American güiro.

This eo has seen a lot of use.

There are numerous other instruments, including the stringed zithers seul and geum, the flutes hun and so, various drums and clappers, and a wooden box called chuk. There are supposed to be eight different instruments, but by my count there are maybe eight types of instruments in total.

So, what's going on with the actual sacrificial ritual itself? We didn't get too close, as only people with special permission are allowed inside the temple. There was a big screen showing the proceedings, but in all honesty, the music and dance were far more intriguing to most of the foreign guests. That said, the actual history and meaning of the sacrifice is in itself very fascinating.

Before starting, the officiants ritually wash their hands at a special station set up on the way to the temple from the eastern door, where the king would typically enter.

What look like incense holders or alcohol basins are actually for washing hands.

The officiants then enter the temple, to perform a series of sacrifices that take about two hours. During these activities, incense is burned, and a variety of foods and alcohols are offered to the spirits, accompanied by much bowing. The whole ceremony closely resembles a large-scale, grand jesa ancestral rite. The ritual offerings are known as jeonpyerye, choheon, aheon, jongheon, bunheon, eumboksujo, and cheolbyeondu.

The way up to Daeseongjeon is crowded today.

The shrine to Confucius is seated on a giant stand inside that looks like a throne. Before the shrine are incense receptacles and various plates and bowls for the ritual sacrifice.

This picture was taken during a much smaller jesa ritual.

All throughout the room, there are many smaller chairs for holding the 38 tablets belonging to the other sages, disciples, and scholars of Confucius who are venerated in this ceremony.

The five sages acknowledged by the Seokjeonje are Confucius, Yanzi, Zengzi, Zisi Zi, and Mencius. As well, ten of Confucius' disciples are included in the ritual. Then, there are the men of virtue, memorialised for their philosophical contributions to Neo-Confucianism, six of which are from Song China and eighteen from Korea.

<p>The Eighteen Men of Virtue from Korea include some very fascinating historical figures. Among them, there are:

Jeong Mongju, a prominent scholar of the late Goryeo Dynasty. At the dawn of the Joseon Dynasty, he was executed for refusing to betray his loyalty to Goryeo. His death symbolically marked the end of Goryeo, and in 1517 he was enshrined in Sungkyunkwan alongside other prominent Korean sages.

Yi Hwang, an alumnus of Sungkyunkwan and former daesaseong (head teacher), might be best known for appearing on the 1000KRW bill. Under his penname Toegye, he penned many important texts.

Yi I was another Sungkyunkwan alumnus whose penname Yulgok was put to many important texts. He appears on the 5000KRW bill and was considered a social reformer and expert in national security.

Jo Gwang-jo was a Confucian martyr who was considered the embodiment of the Seonbi Spirit. He was sentenced to death by poison during the Third Seonbi Purge of 1519.

One of the members of my group discovered that seonbi robes were for sale next to Munmyo, and before I knew it half of my group was changing into the robes.

Not surprisingly, this attracted a lot of attention.

Afterwards, one of the Sungkyunkwan Confucianists led us on a tour of the rest of the historic campus, and then we went into the neighbouring Yurim Hall for a meal.

It was an incredible honour to attend this ages-old ritual event. It is impressive that the Seokjeonje has been kept alive in Korea and nowhere else, and the Sungkyunkwan Seokjeonje is the greatest, one solemn mass performance in a wonderful historic location.

Confucianism may not seem as relevant in the modern age, and it may flippantly get the blame for many of modern Korean society's social ills, but its positive influences on Korean society cannot be overlooked. Embodied in the Seonbi Spirit of those great Koreans enshrined in Daeseongjeon, Confucianism was the source of great social reforms under the Joseon Dynasty, and influenced the creation of Hangeul, the Korean native written script.

Confucianism falls somewhere between a philosophy and a religion, with the veneration of Confucius and his disciples coming close to deification--but not much moreso than any ancestral recipients of a family jesa. Unlike other religions, Confucianism is concerned with realising an ideal material world, rather than hoping for reward in the afterlife. The spirit of Confucianism--as well as the spirit of the Korean people--is kept alive with the Seokjeonje twice every year.

The next Seokjeon Daeje will be held at Sungkyunkwan sometime in September.

By Jon Dunbar for the Korea Blog