View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

An overview of Hwang Sun-Won’s fiction

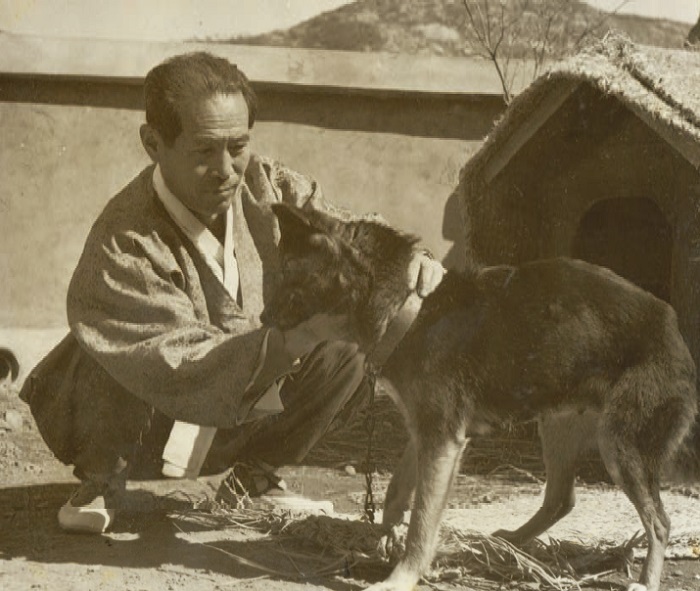

Hwang Sun-Won (1915-2000) is one of the great Korean authors of the twentieth century. Hwang started writing in 1931, publishing his first poem, “My Dream,” at the age of sixteen, and by June 1936, he had published two volumes of poetry. But with the publication of a collection of short stories in 1937, he started anew as a writer of fiction. Since that time, immersing himself in the writing of fiction for over fifty years, Hwang managed to avoid being caught up in fashions of the times and stayed consistently true to the course of literature, creating his own distinctive fictional universe. During this period, he released 104 short stories, seven novels, and one novella.

In his early period as a writer, Hwang usually depicted folk customs in his works. He devoted himself to the sensuous description of human interiority, and showed great affection for sentiments native to Korea and the people’s traditional spirit. Traditional farm towns or mountain villages serve as the stage for stories of the kind described above, stories such as “Cock Ritual” (1938), “Stars” (1940), “Children of the Mountain Village” (1940), and “Serenade” (1943), in which Hwang portrays the lives of poor yet simple people, and the beauty of their powerful, primal will to live.

After 1950, Hwang sought to portray the ideal of mother love through a variety of female characters. In stories such as “Cranes” (1953) and “Rain Shower” (1953), his short fiction reached full maturity. Meanwhile, in great novels such as Living with the Stars (1950), The Descendants of Cain (1954), Trees on a Slope (1960), Sunlight, Moonlight (1962), and The Moving Fortress (1973), he explored in great depth the question of eternity and the problem of existential solitude and alienation.

Shamanism in Hwang’s fiction

One of the defining aspects of Hwang’s works— from the short stories of his early period to the novels he wrote towards the end—is the original way in which shamanistic elements are incorporated. Shamanism originated along with Korean history itself. Deeply rooted in the life of the people, it formed the substratum of traditional culture and was passed down from generation to generation. Hwang suffused the short stories of his early period with elements of this traditional belief system, which bore with it the heritage of native sentiments and traditional spirit. In the case of these early stories, set in farm towns or mountain villages – “Cock Ritual,” “Stars,” “Children of the Mountain Village,” and “Serenade” – a chain of shamanistic elements comprises the narrative development and also acts as the medium for important thematic imagery. Examples of this include the slaughter of the rooster in “Cock Ritual” as the motif of a sacrificial rite; the magic of the curse in “Stars” the folktale in “Children of the Mountain Village” as the motif of the rite of passage; and the story about the shaman in “Serenade” that functions as a metaphor for the darkness of the times.

In the novels he wrote from 1950 until 1970, besides painting the palette of Korean sentiments, Hwang devoted attention to the problem of social change and the fundamental question of human existence. In the course of doing so, he continued to incorporate shamanistic elements in a number of the works. In the novels Sunlight, Moonlight, and The Moving Fortress in particular, the world of shamanism is foregrounded and fully realized, and it functions as the core motif of thematic representation and plot development. In Sunlight, Moonlight, the narrative structure consists of a line of questioning: What is the source of the protagonist’s loneliness that he feels is inescapable, and how can he ease this loneliness? Hwang contrasts this series of questions with a myth about the Bull Prince circulated among butchers. The Bull Prince Myth, based on the popular deification of cattle, was passed down through the generations by those in the butcher caste, who gave it a unique narrative structure so that, over time, it changed in form until it even came to include the function of a shamanist ritual.

The Bull Prince Myth can be classed as a monomyth, with the hero’s departure, initiation, and return constituting its basic structure. The Prince is the son of the Heavenly King, and he is raised within the order of the Celestial Kingdom. Viewed in terms of his noble status, we can see that the protagonist fits the characteristics of the hero of a monomyth. Being sent to the world below to toil for humans as a punishment for breaking the rules of heaven is analogous to the hero’s setting off on adventures in order to fulfill his great destiny. Likewise, the prince’s return to heaven after giving up his labor and life for humans is comparable to the hero overcoming adversity and achieving his intended goal.

This myth of the Bull Prince forms the structural motif of Sunlight, Moonlight, Hwang’s novel about the spiritual journey of a protagonist who undergoes deep-rooted suffering as he discovers he is descended from butchers, and his path towards alleviating it.

Contrasting Shamanism with Christianity

In The Moving Fortress, the factors controlling Koreans’ deep consciousness and surface consciousness, namely, shamanism and Christianity, are pitted directly against each other, and through this technique, the author lays bare the confused structure of the Korean psyche. In the course of Christianity’s coming to Korea and taking hold, it became mixed with shamanism, losing its essence and becoming distorted. In other words, the novel adopts a neutral perspective to criticize the negative way in which shamanism and Christianity have affected one another.

For this project, the writer incorporates a vast amount of cultural historical research on shamanism, a belief system that has been deeply rooted in the people’s psyche since ancient times, and he comes to grasp its true nature, as well as its present reality and limits. He criticizes shamanism from an objective perspective, contrasting it with Christianity, and suggests the possibility of transcending its limits.

In the novel, Hwang explores the spiritual world of Koreans through the lives of three characters: Jun-tae, an agricultural engineer who claims that Koreans are by nature a nomadic people, and who lives and dies a nomad of this type; Seong-ho, a pastor who has borne the weight of something like original sin since having an affair with his teacher’s wife as a young man, and has gone on to embrace all kinds of hardships while walking a path of contrition in search of truth; and Min-gu the folklorist, a pragmatist always able to change religious or scholarly convictions for his own profit, who becomes deeply immersed in the study of shamanism.

Today’s Korean Christianity, like shamanism, takes on a sickly and abhorrent aspect if viewed from Hwang’s perspective: it is like “a moving fortress” adrift on a shaky foundation. The writer says that if we are to restore the foundation to its original state and build a proper stronghold, then we should walk along a road like Seong-ho’s: the road of perceiving God in His truth, and putting pure faith into action.

Archive of “the people’s memories”

Hwang Sun-Won’s writing encompasses sixty years of history, spanning events such as the occupation of Korea by Japan, liberation, and national division. Even if we were to discuss his works alone, from his debut in 1931 with the poem “My Dream” to his short story “Rain Shower” (1953), extending through to his last novel Dice of the Gods (1982) and his return to poetry with “On Death” (1992), his writing spans over sixty years. As a result, his writing is an archive of “the people’s memories,” (Yu Jongho) and constitutes such an enormous body of work that it approaches being what Kwon Youngmin has described as “the entire history of Korean literature after liberation.”

Born in 1915 in Taedong, South Pyongan Province, Hwang began his literary career with the publication of “My Dream” in the journal Eastern Light (Donggwang) in July 1931. After that, he graduated from Osan Middle School in 1934, and left for Tokyo to attend Waseda High School. In the same year, together with Lee Haerang, Kim Dongwon, and others, he established a performing arts collective called the Tokyo Student Arts Group. Hwang’s first poetry collection, Wayward Songs (Bangga, 1934), included “My Dream” and twenty-six other poems. In particular, he writes about the wild romantic passion of the teenage years in a fiery and resolute tone, just as Yang Ju-dong (writing under the penname Mu-ae) had done in Seomun.

Tokyo Student Arts Group

When performing a survey of Hwang Sun-Won’s literary relationships, the first group that must be considered is the Tokyo Student Arts Group. This was a theater collective established in Tokyo in 1934 for Korean students studying there, and it launched a theatrical reform movement. Students majoring in literature, drama, and film contemplated their concerns, and eventually, Park Dong-geun, Hwang Sun-Won, and thirteen others developed a new arts movement that had as its goals sound theatrical development and the stirring of the people’s spirit. They published the first bulletin in the history of Korean university theater, titled Act (Mak). Under the slogan, “the new theater of Joseon will begin with original scripts,” their first performance was held in June 1935 at the Tsukiji Small Theatre, where the Japanese theater reform movement had begun. The theater company grew and matured while staging Ju Yeongseop’s one-act play, Naru, and Yu Chijin’s three-act play, The Ox, but was disbanded in 1940 due to a crackdown by the Japanese government.

Surrealist leanings: Three Four Literature club

The second group Hwang was involved in was the “Three Four Literature” club. Three Four Literature was a literary magazine that published six consecutive issues from September 1934 until December 1935. It was published and edited by Shin Baeksu, with a first issue that ran up to 200 copies. Apparently the title Three Four Literature was chosen in order to emphasize that it was published in 1934. Jung Hyunwoong and ten others were the founding members of the club, and Hwang Sun-Won participated after the third issue. The published works generally demonstrated surrealist tendencies, and were modernist in character.

Towards imagism: Creative Writing club

The third literary group was the “Creative Writing” club. Creative Writing was a literary magazine published from November 1935 until July 1937, for a total of three issues. The editor and publisher of the first issue was Han Jeokseon, the second was Han Cheon, and the third was Shin Baeksu. Ju Yeongseop contributed five poems for the first issue, Jeong Byeongho five, Shin Baeksu two, Han Cheon three, Jang Yeonggi three, and Hwang Sun-Won three. It was during this time, in May 1936, that Hwang Sun-Won published his second collection of poetry, Antiques. In it he demonstrated a modernist orientation, with poems that were constructed using images or short single phrases, generally about his immediate impressions of an inanimate object.

Towards the psychological: Dislocation club

The fourth group was the “Dislocation” club. A total of three issues of Dislocation were released, from April 1937 until February 1938. Park Yongdeok was both editor and publisher, and it was published in Pyongyang. A distinguishing feature was that its first publication was referred to as “book one” rather than “the first issue.” The main writers featured in the magazine—novelist Kim Iseok, Kim Jogyu, and Hwang Sun-Won—published Dislocation as a friendly, collaborative effort. Critics have described the writing as psychological in approach.

Literary colleagues Kim Tong-ni, Son So-Hui, Kim Malbong, Kang So-cheon, and Seo Jeong-ju

After migrating from North Korea to the South, Hwang developed close relations with fellow writers Kim Tong-ni, Son So-Hui, Kim Malbong, Kang So-cheon, and Seo Jeong-ju. Hwang’s personal friendship with Kim Tong-ni (1913-1995), whose novels exemplified “pure literature,” was so deep that Kim could joke about his good moral character saying, “Hwang could pass through the ‘Rain Shower’ without getting wet.” Hwang also closely communicated with other literary figures that were taking refuge in Busan during the Korean War in the early 1950s, including Kim Tong-ni’s wife, leading female novelist Son So-Hui (1917- 1986), and Kim Malbong (1901-1962), a writer who made his name writing popular fiction. Hwang is also known to have grown close to children’s writer Kang So-cheon (1915-1963), with whom he shared a sense of belonging as a writer who had migrated from the North.

Hwang had a faithful confidant in his childhood friend, literary translator Won Eung-seo (1914-1973), upon whose advice he rewrote the final passage of “Rain Shower.” Hwang had an established reputation as a drinker, and after Won died in 1973, wherever Hwang was drinking, he was known for pouring out the final glass of soju into the air as a tribute to his old friend. Hwang was also known to be friends with fellow writer and contemporary Seo Jeong-ju (1915-2000), and this relationship was close enough for Hwang to dedicate his poem “The Meaning in the Void: For Seo Jeong-ju” to him.

Nurturing literary talent

While serving as a professor at Kyung Hee University from 1957-1980, Hwang helped form the Kyung Hee Literary Circle together with other writers working at the same school, including Kim Kwang-seop (1905- 1977), best known for the poem “Seongbuk-dong Pigeon,” Chu Yo-sup (1902-1972), who wrote the short story “Mama and the Boarder,” and the prolific poet, Cho Byeonghwa (1921-2003). In a famous anecdote, whenever Hwang was a judge of the fiction category of a daily newspaper’s annual spring literary contest he would leave the decision to other committee members if his own students’ work reached the final round. Students who became writers under his tutelage include novelists Jeon Sang-guk, Cho Se-Hui, Cho Haeil, Kim Yongseong, Han Su-san, Ko Wonjeong, Park Deok-gyu, Kim Hyoung Kyoung, Lee Hye-gyeong, and Seo Hajin; poets Park Edo, Lee SungBoo, Cho Taeil, Jeong Ho-seung, Lee Young-chun, Park Nam-cheol, Ha Jaebong, Lee Moon-jae, and Park Jutaek; critics Kim Jonghoi, Shin Deok-ryong, Ha Eung-baek, and Mun Heungsul; children’s writer Kim Yongheui; television and radio writers Shin Bongseung, Park Jinsuk, and Kim Jeongsu; and essayists Seo Jeongbeom and Lee Jeongwon. Lee Ho-cheol, Suh Ki-Won, Choi Inho, Kim Jiwon, and Kim Chae-Won were writers who debuted on the basis of his recommendation and went on to become active in the literary scene.

Kyung Hee University offered Hwang a doctorate in literature, but he showed great integrity in refusing it, observing, “I have enough degrees for a novelist.” Cho Haeil expressed his admiration in the following statement: “The most striking aspect about Professor Hwang, both in the world of literature and as a human being, is his integrity.” Reminiscing about his former professor, poet Jeong Ho-seung stated, “He kept himself unstained from the world, and by showing pride and grace in his life and work he demonstrated the true spirit of a writer.” Hwang’s oldest son Hwang Tong-gyu (b. 1938), a poet and scholar of English literature, is Professor Emeritus at Seoul National University. He debuted in the journal Hyundae Munhak, courtesy of Seo Jeong-ju’s recommendation, and has won great renown as a poet.

Hwang Sun-Won’s love of his country and native language is shown in the following anecdote. During his early childhood under the Japanese occupation, his son Hwang Tong-gyu once asked him why they weren’t taught Japanese in their family; grief-stricken, the elder Hwang responded that he must have gone wrong somewhere in raising his son. Hwang’s conviction that “a writer speaks through his works” prevented him from writing miscellaneous essays and articles outside of the genres of poetry and fiction, and in this respect, his nickname Hwanggojip (very stubborn person, with a pun on the name Hwang) suited him well. He devoted his life to being a writer, and so outside of a writer’s duties of being a professor and member of the National Academy of Arts, he did not seek honors, titles, or government posts. Now, buried in the Sonagi Village graveyard together with his wife, Yang Jeong-gil, who died in 2014, Hwang is looking down upon the blue skies and beautiful mountain ridges of scenic Yangpyeong County.

Scenes from Sonagi Village - Spring to Fall, 2015

Sonagi Village

Sonagi Village has been visited by over 100,000 guests since its doors first opened on June 13th, 2009. After the author Hwang Sun-Won passed away on September 15th, 2000, professors of literature and Hwang’s former students sought to create a cultural space for the nation to be able to share Hwang’s literature with as many people as possible. It was then that they chose a particular line from “Rain Shower” (Sonagi): “The girl was to move to Yangpyeong-eup tomorrow.” In 2003, a partnership between Yangpyeong-gun and Kyung Hee University paved the way for the creation of Sonagi Village.

Recalling One’s First Love – Centennial Anniversary Events

The 100th anniversary of Hwang Sun-Won’s birth was celebrated with a variety of events throughout 2015. The first events of many planned for the year were the “Saturday First Love” concerts. From March through May, a “Literature Night” was held on the last Saturday of each month in the Hwang Sun-Won Literary Center Assembly Hall. Newscaster Grace Pyeon (Pyeon Sojeong) was the emcee for these events, which included deeply-felt poetry readings by the poets Jeong Ho-seung and Choi Myeong-ran, as well as the dulcet tones of a saxophone performance from Son Hyeong-ok, the grand voice of the tenor Choi Yong-ho, and a subtle performance by the guitarist Kim Yeong-su.

The second event was the “Writing a Sequel to ‘Rain Shower.’” Five selected short stories written by Kyung Hee University alumni—Jeon Sang-guk, Park Deok-gyu, Lee Hye-gyeong, Seo Hajin, and Gu Byeong-mo—were published in the summer edition of the quarterly magazine, Daesan Munhak. The authors used their imaginations to create continuations of Hwang’s classic, “Rain Shower.” Jeong Sang-guk’s version, “Harvest,” shows the young protagonist, now in middle school, unable to forget the young girl as he navigates the growing pains that come with puberty. Park Deok-gyu presented “A Person’s Star” which portrays the young girl as a being from another world and shows her travels in the land of stars through a first person monologue. Lee Hye-gyeong brought to life a story where the boy has grown into a young man of the 21st century and is living the life of a laborer in the city all the while keeping alive the memory of the little girl in her piece, “That Uneraseable Muddy Water.” In Seo Hajin’s story “Another Cloudburst,” three years after the girl has passed away, the boy meets another student who resembles her. Gu Byeong-mo wrote his story “Disturbance” about the boy putting the jacket back on that he wore with the girl and going out to the river again a few days after she dies.

The third event commenced with the publication of the five authors’ homages with the opening of the “Writing a Sequel to ‘Rain Shower’ Contest” for all lovers of literature in the month of June. The contest was held for the dual purposes of expanding Hwang Sun-Won’s literature to the public and instilling his literary spirit. There were 121 entrants in the high school division and 195 entrants in the regular division. The judges emphasized that they were looking for “sequels” which had both a sense of continuation from the original, and yet also maintained merit as independent stories.

Drawing One’s Father – 4th Annual Hwang Sun- Won Cyber Writing Contest

The “Hwang Sun-Won Cyber Writing Contest” this year was held for essays, accepting submissions for the duration of May. The contest was part of the 12th Annual Hwang Sun-Won Literary Festival, but it took place four months ahead of the festival which was held in September. The topic for this year’s Cyber Writing Contest was “Father.” There were 227 participants, and with May as “Family Month” in Korea, “Memories of Father” came to mind as writing on this topic allowed contestants to reflect upon the beginning of their lives.

Raising the Curtain on 12th Annual Hwang Sun- Won Literary Festival

On September 11th, 2015, under the banner of “Celebrating 100 Years Since the Birth of Hwang Sun-Won,” a seminar shedding new light on “Hwang Sun-Won’s Life and Literature” was held in the third floor assembly hall at the Sonagi literature center. After watching a video of a condensed overview of the author’s life and work, the president of the Hwang Sun-Won Memorial Society, Park Yi-do, gave a few words of welcome followed by the keynote speech from former president of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea, Kim Joo Youn. The first presentation was by Yonsei University professor Jeong Gwa-ri titled, “Elements of ‘Advanced-ness’ in Hwang Sun-Won’s poetry from the 1930s.” The second presentation, by Kyung Hee University professor Baek Jiyeon, was on the topic of “A Story’s Prospect: Focusing on Hwang Sun-Won’s Living with the Stars, and the final presentation was given by professor Kim Chunsik from Dongguk University, titled “Hwang Sun- Won’s Poetry and Exchange Studies in Tokyo.” A group discussion followed as researchers gave their opinions on Hwang’s short form poetry from the 1930s and the possible influences from Japanese haiku and American or European Surrealism or Imagism.

Sonagi Village Literature Prize – 4th Sonagi Village Literature Prize Awards Ceremony

On September 11th, around 100 guests gathered in the third floor assembly hall for the 4th Sonagi Village Literature Prize Awards Ceremony, hosted by the poet Kim Ki-taek. The 20 million won “Hwang Sun- Won Literature Research Prize” was presented to Korea University professor Choi Dongho for his book, Study of the Man Hwang Sun-Won and His Literature. Choi’s book shows a new understanding of the author through the sincerity in his research of Hwang’s human side, his relationship with his wife and the literary world, creating imagined conversations with the author, and discovering new examples of his poetry from the 1930s. The “Hwang Sun-Won Literature Prize” was awarded to the author Gu Byeong-mo for his novel, I Pray That Thing Is Not Me. The winning work captures the moment when everyday normalcy ruptures, showing a unique imagination and attractive literary approach.

Literature and Drawing Contests for Elementary, Middle, and High School Students and 15th Anniversary Memorial Ceremony

The highlight of the 12th Annual Hwang Sun-Won Literary Festival was the writing and drawing contest on September 12th for Elementary, Middle, and High School students. The subject for the writing contest was “Stain,” and the subject for the drawing contest was “Walnut.” After the topics were announced, the entrants could be seen scattered all over Sonagi Village working intently on their creations.

Later that morning, Hwang Sun-Won’s surviving family, close friends, and literary figures gathered in front of his grave to observe a moment of silence and then perform a memorial ceremony honoring the fifteenth year of his passing.

The deadline for the students’ work was signaled in the early afternoon by a shower from a man-made cloudburst machine before activities continued with two hours of lectures and performances. The team from the “Saturday First Love” concerts was on hand for tranquil poetry recitations set to music as the beautiful playing of the Hanyang Elementary School Junior Orchestra flooded Sonagi Village. When the performance ended in the late afternoon, the day was completed in a lively fashion with awards given to the winners of the writing and drawing contests.

A Walk Under the Blue Autumn Sky – 6th Annual Literary Village Tour with writers

On Sunday, September 13th, the 6th “Annual Literary Village Tour with writers,” was held as the final event on the last day of the literary festival. The Village Tour started in the morning with around twenty participants including two authors and two critics split into three teams that set to explore both inside the literature center and the surrounding Sonagi Village.

Beneath the clear autumn sun, participants shared food and conversation then gathered in front of the literature center to take a group photo. Once the photo was taken, the man-made cloudburst machine was turned on and a fountain of water was shot meters into the air to rain down on the Sonagi Plaza. The 2015 “Celebrating 100 Years Since the Birth of Hwang Sun-Won,” and 12th Annual Hwang Sun-Won Literary Festival came to a poetic end in the harmony of nature and the man-made, under the warm sun and a vibrant rainbow.

* Article from the List magazine published by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea