View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

Transformation and Idea Formation in the Poetry of Seo Jeong-ju

An interesting feature of “Midang” Seo Jeong-ju’s poetry is his poetic transformation. Midang said himself that his study of literary expression was a process of being influenced by the poets who went before him and then trying to overcome their influence. Accordingly his poetry draws a kind of “poetic contour map,” creating a position for Midang as a literary heir to Korean poetry. There is more than meets the eye in this confession of the process of composing poetry as combining passion for original creativity and studying the poets who came before. This statement served to make the absolute core of Midang Seo Jeong-ju’s sense of identity as a poet visible. It reflects the “traditionalism” and “original creativity” which made up the two pillars of modern Korean poetics, and the way in which they served as the most central “aesthetic norms” in the process through which his poetic world unfolded.

The linguistic expression in Midang’s first collection of poetry, Hwasajip, has at its base the “tradition” that he inherited through his study, but the life force contained within that expression is laid bare through a kind of Nietzschean physical, sensory revealing. The main characteristic of Midang’s poetic expression is its freewheeling nature, with image, musicality, direct language, and poetic context going back and forth between the lines. In terms of form, these characteristics are very clearly closely related to the formal character of the poets he cited as having influenced his work. However, rather than being based on his incredible technical ability, Midang’s originality lies in his sense of identity as a poet constantly tackling the question of “What is poetry?” Having opened his eyes to “loving one’s fate” through Nietzsche’s concept of the “human,” it is clear to see that the core of Midang’s poetry is taken up by his collection Hwasajip. In the transformation of his poetry then, rather than seeing a transformation in terms of form, we see a change in his fundamental outlook on life.

By accepting the physicality and instinct of “human becoming,” being faithful to one’s desires and a love of fate as one’s own volition, the poems in Hwasajip present a strong life force and bodily physicality. This was impossible to find in earlier works of poetry in Korean, and meant that Hwasajip was an epoch-making collection, bursting with unconditional human will. In an extremely unusual way for the time, Hwasajip shows a strong volition to go beyond the usual standards of beauty defined by what is “moral” or determined in relation to “good and evil.” In this regard, it created a landscape that had not been seen before in Korean poetry, and a poetic specificity that has been difficult to find since then.

The genius poet Yi Sang called Seo Jeong-ju a “terrifying character,” having read his poem “Leper.” In “Leper” Yi Sang saw a unique work of poetry, both desperate and sad, but also one that contained an unyielding will, a strong volition for life, more animal than human. “Leper” was a completely new kind of poem, unlike anything else in Korean poetry at the time. This short poem represents an unconditional “will for life” and “composure of one winning in spirit, transcending fate” that went far beyond the morality of the causes of the oppressed sentiments of the colonial subjects of the era. Therefore it could indeed be read as a “terrifying” work, a strong life force lay bare.

Examining Midang’s poems in Hwasajip, we can say that the way of expression, rather than representing proficiency or completeness, displays frank language, coming close to the spoken “voice” or raw “movement.” This voice plays out in the midst of circumstances wherein Midang’s “love of fate” and “reliance on life” are oppressed by objective external situations and hierarchies. To put it another way, in setting up all of the adverse conditions of the time, such as original sin, good and evil, the subjugated position of colonial subjects, and historical ordeals, as “fate,” Hwasajip was a collection of poetry that encapsulated being battered by such fate and coming out the other side, only to turn around and attempt to embrace it and hold it close.

“Self-Portrait” is a poem that touches upon the impossibly deep subconscious abyss inherent in the feelings of inferiority due to the oppression suffered by colonial subjects. The pathological conditions of shame in the concepts of “blood,” refusal to “repent” and being either a “convict” or an “idiot” show that, for the narrator, there is already no chance that an escape will be granted. This sense of despair faced with obstruction on all sides is a feeling that appears frequently in the poems in Hwasajip, including “Wall,” and in works written later in the colonial period, such as “Ode to the West Wind.”

In this period, Midang strove to go beyond the despairing reality, which came close to complete degradation or terrible fate by means of human volition or superhuman life force. This is something he accomplished and successfully expressed in “Self- Portrait.” The images of blood and refusal to repent are at once an outright refusal of a cursed fate and at the same time a complete embrace of it. Inside the love of one’s fate which does not deny all that stems from divine punishment but rather draws it near, feelings like shame and sorrow are still present; but in this context such feelings are understood separately from their negative connotations. On the contrary, every single emotion becomes the object of aesthetic appreciation or spiritual inquiry. Far beyond the boundaries between good and evil, pleasure and displeasure, the posture of embracing destiny with spiritual will is a form of imagined triumph and comes close to being a kind of aesthetic experience. In fact, the accomplishment of both “Leper” and “Self-Portrait” draw near to a form of paradoxical aesthetics.

While Midang’s poems written during the colonial period, including those in Hwasajip, display a strong will to resist universality with the will of the individual striving to transcend historical violence, in the 1940s, quite unexpectedly, the traditional world of “Yi Dynasty porcelain” and sky-colored celadon became a strong theme in his poetry. We can begin to find an explanation for this change by considering his activities during this time. Seo Jeong-ju was married in 1938 and, following the publication of Hwasajip, he had a son in January 1940. Then, in October of the same year, he left for Manchuria alone, and stayed there until early February 1941. It seems as though his travels to Manchuria were made out of economic necessity, but from the fact that his travels were so short we might imagine that it was a period of unbearable wandering and drudgery. In this period, it appears as though traditional beauty, such as that of antiques and Yi dynasty porcelain, is what filled his inner emptiness and bolstered his sense of identity.

While resignation and tradition are very much in opposition to Nietzsche’s love of fate and volition, they also share a point of commonality. In the way that these two approaches do not accept within any value or external fate, they in fact resemble one another. If resignation or adaptation are fundamentally an abandonment of oneself, a voluntary defeat, then loving one’s fate is a kind of “triumph of spirit.” These two are both a kind of “pose” or “demeanor,” and ultimately boil down to the same form. In this way, Midang’s poetry shows a process of transformation from an aesthetic form that gushes forth with spiritual triumph, physical life, and volition, to an aesthetic form that conceals and suppresses life through defeat and adjustment.

Seo Jeong-ju’s Literary Peers

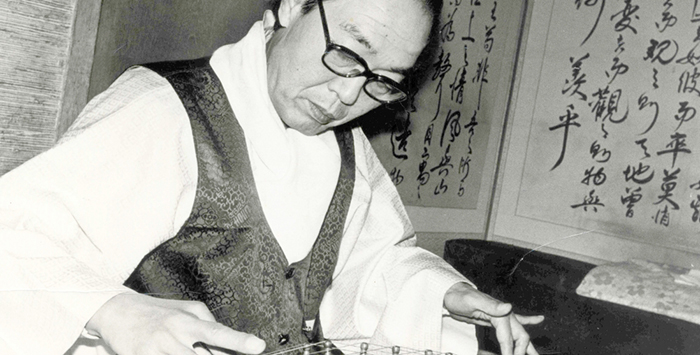

The oeuvre of “Midang” Seo Jeong-ju (1915-2000) constitutes the great mountain range of 20th century Korean literature: towering, vast, stretching powerfully into the distance. And, like many trees and plants living in the area, successive generations of poets grew up within its fold. In this respect, Seo Jeong-ju can be called the father of Korean poetry. His creative period lasted almost seventy years, and during this time, he released fifteen poetry collections and more than 1,000 poems. Now, a twenty-volume complete edition of his collected works will be published in commemoration of the centennial of his birth.

Midang Seo Jeong-ju’s poetry has no antecedents. From the time he started out, Seo’s inimitable style set him apart from poets of previous generations. In his first collection, Hwasajip (1941), written in a rugged, aggressive hand, he brought form to the churning vortex of emotions and human sexual desire. Existential individuality, anxious and agonized, suffering the coexistence of contradictory qualities, can be found throughout these poems. The emergence of such a distinctive artistic voice was also the signal shot indicating that Korean poetry had entered the modern age. Speaking figuratively, one could say that his work represented the birth of the complex system in the field of Korean literature.

Seo appreciated the work of older contemporaries such as Kim Sowol (1902-1934), Joo Yohan (1900- 1979), and Kim Yeongrang (1903-1950), but he did not follow directly in their footsteps. Moreover, he resolved to outdo Chong Chi-yong, a poet at the forefront of Korean modernism who put a premium on technical brilliance. Rather, Seo’s early poetry originates somewhere outside of the bounds of Korean literature. His major influences include the works of Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky, Baudelaire, Hugo, and Li Po; the philosophy of Nietzsche touching on the world of Greek myths, and Zarathustra, the Overman; and the ideas of Siddhartha.

From the moment he debuted as a poet, he could be called a genius. Establishing his distinctive artistic personality, portraying Eastern and Western values mixed together in anxious turmoil, Seo started to soar high above the contemporary literary horizon. From the time he released his second poetry collection, he strove to be faithful to an aesthetic that could be called Eastern, Korean, and traditional. By taking refuge in the atmosphere and form of traditional lyric poetry, he reached the core of Korean literature, strongly influencing the writers who followed after him. Among contemporary poets, his ideological and emotional leanings were similar to those of the Green Deer Group (Cheongnokpa), consisting of Pak Mogwol, Pak Tu-jin, and Cho Chi-hun. Far removed from the revolt against social inequality and class struggle, these poets cultivated an environmentally-friendly attitude, a longing and nostalgia for folk communalism, and an appreciation for the aesthetic properties of language itself.

For all intents and purposes, Seo Jeong-ju and the Green Deer Group became the vanguards of Korean modernism. With the outbreak of the Korean War, not only did the country become divided, but many senior literary figures became Communists, and for this reason, the young poets ended up taking on the mantles of the great masters. They also became professors at the top private universities, where they came to exercise powerful leadership and influence.

Seo’s brand value consisted of tradition and lyricism. The theme of tradition, in particular, did not originate with Seo, so using this as a focal point, we can naturally trace his position within a web of like-minded senior and contemporary writers. If we focus on shamanism, which can be considered an indigenous Korean belief system, then Kim Sowol, Kim Tong-ni, and Baek Seok should be mentioned as Seo’s contemporaries. Kim Sowol sought to identify the importance of the spirit with the creative principle in his own poetry. Kim Tong-ni (1913-1995), a close friend of Seo, maintained that shamanism had been practiced continuously from the time of the Silla Kingdom until modern times, identifying characteristics of it in an ancient aesthetic philosophy known as pungryu-do. These two men, the novelist and the poet, informed their works with the belief that the world of legends and myths continues to impact modern life. Meanwhile, Baek Seok (1912-1996) hoped to resuscitate vanishing shamanist traditions through a folk culture revival. For this reason, catalogs with minute details pertaining to cultural practices appear throughout his works.

Looking at another important category of tradition, we can think of Seo as being connected to his peers through a common interest in Buddhism. Han Yong-un, Cho Chi-hun, and Ko Un would be his peers in this kinship web. Han Yong-un (1879-1944) actually held the social title of monk. By communicating profound Buddhist doctrines in the form of smooth, readable letters, Han contributed to raising Korean poetry to a new level of philosophical elegance. During his early period, Cho Chi-hun (1920-1968) produced poems with a Buddhist sensibility, but beginning in his middle period, he became preoccupied with the concepts of “the folk” and “spirit.” Eschewing resignation and passivity, he showed righteousness and a spirit of active resistance in the face of contemporary reality. In addition to being Seo’s student, Ko Un (b. 1933) has discovered tradition anew by writing Buddhist poetry that is distinguished for its concise and hard-hitting literary style, and has worked steadily at translating it and making it known internationally.

Seo Jeong-ju’s emphasis on tradition affected the succeeding generation of poets even at the stage when they first debuted. Because he often served as a judge of new writers’ contests, he naturally applied his standards and taste to the procedure for selecting good poets. He can be regarded in the role of teacher to these writers, even if he didn’t teach them directly. For this reason, we could write a literary lineage showing the pupils Seo mentored. It would be meaningless, however, to list their names: there are too many of them, and not all of them were able to carve out a domain for themselves. Rather, in a strict sense, the category of Seo Jeong-ju’s literary relations consists of those poets who have been inspired by Seo’s literary accomplishments to write poetry in their own style. Representative examples include Pak Jae-sam, Kim Chun-su, and Jeon Bong-geon.

Pak Jae-sam (1933-1997) borrowed characters from folktales and legends to use as subject matter in his poems, and in this regard, he can be compared to Seo. Pak’s portrayals of characters such as Chunhyang or Heungbu, however, are much more realistic and down-to-earth than Seo’s. Kim Chun-su’s (1922-2004) work reflected aspects of Seo’s early period in that he attempted to unite modern Western and traditional Korean styles, but by placing unusual stress on rhythm and imagery, he strove towards his own goal of creating a new form of Korean poetry that “existed for the sake of language alone.” Jeon Bong-geon (1928-1988) can also be counted as an important relation for the way that he embraced tradition. By taking Chunhyang’s life in prison as his subject matter and overlaying it with the image of himself being wounded in the Korean War, he demonstrated the unusual technique of projecting himself onto tradition.

In terms of female poets, Moon Chung-hee is the most closely related to Seo. She made the passion and lunacy that characterized his early period completely hers, while appropriately tempering these tendencies with self-moderation and sound judgment. If Seo has been assessed to be very rational and yet a shamanist poet, at the same time, Moon Chung-hee has also achieved this degree of balance.

Midang Literary House and Events for the 100th Anniversary of Seo Jeong-ju’s Birth

Midang is the penname of the poet Seo Jeong-ju. It carries the meaning of “not yet fully grown” or a “wish to forever be a boy.” The Midang Literary House is located in the poet’s hometown of Jeollabuk-do Province, Gochang-gun, Buan-myeon, Seonun-ri. The positioning of the Literary House is quite special. There is a large mountain (Mt. Soyo) behind, the ocean (Byeonsan Beach) in front, the poet’s house of birth to the left, and his grave to the right. Even throughout the rest of the world, it is rare to find a poet’s life, death, and memorial all gathered in one place, in the midst of beautiful, natural scenery.

The Midang Literary House was originally a school, a branch of Bongam Elementary. When the school was scheduled to be closed due to the dwindling number of students in the remote village, cultural administrators had the idea to repurpose the building as a memorial hall for Seo Jeong-ju. With 5,000 of the poet’s personal effects on display, visitors can see the majority of Seo’s writings as well as various everyday items he used. There are more personal effects preserved at the Midang Literary House than at any other author’s memorial hall in all of Korea.

One of the Literary House’s peculiarities is the five-story exhibition tower designed by the architect Kim Won. Many of the exhibits are on display on the ground floor of the school building, but the tower holds the most precious items. If the single-story school building is said to resemble the ocean, then the tower represents the mountains that surround the village. It is a man-made construction combining the horizontal and vertical to create the ocean and the mountains, but it succeeds in replicating the harmony of nature found in the poet’s hometown.

This building doesn’t try to stand out from the landscape. Instead of trying to overwhelm or resist its surroundings, it is comfortably nestled in nature’s embrace. One could say that this was the architect’s philosophy. The Midang Literary House is in the center of the village, but it doesn’t give off that sort of feeling. It seems to have kept alive the land’s original “school”- like personality quite well.

When climbing the stairs to the fifth floor of the tower, it feels as if you are climbing a mountain. Pictures of the world’s most famous mountains are hung on the walls to see as you ascend the stairs. These pictures are from a collection of 1,628 mountains that Seo memorized as he got older. As he reached his mid-seventies, he challenged himself to memorize these mountains as a way to prevent memory-loss. The Midang Literary House purposefully displayed these photos as a testament to the poet’s tireless efforts even as he aged.

The Midang Literary House was opened one year after Seo passed away, on November 3rd, 2001. Every year around this time, the village hosts a literary festival to commemorate the opening. The highlight of the festival is to present that year’s best poet with the Midang Literary Prize. This award, which is sponsored by the Korean newspaper Joongang Daily, has the interesting tradition of holding the awards ceremony in the poet’s hometown.

Around the time of the festival, the entire village, including the mountain that is the site of the poet’s grave, is covered with beautiful, fragrant chrysanthemums. This makes it a special event commemorating Seo’s most famous poem, “Beside a Chrysanthemum.” Many people can come and be moved by the sight of thousands of yellow chrysanthemums against a background of sky blue.

From the beginning of this year, events planned for the 100th Anniversary of Seo Jeong-ju’s birth have attracted much interest in the literary world. In particular, there was an explosion of interest when previously unpublished poems were found in the over fifty years of notes that were lovingly kept by the poet and made public. The response to these poems was mostly positive and many agreed that they were of no lesser quality than his previously published ones.

Starting in the spring, the Midang Memorial Society held the first of the 100th Anniversary performances. Around 500 people gathered at the 300- seat Dongguk University theater and were completely immersed in the program, which included listening to poetry recitations and reminiscences about the poet, watching videos recorded of the poet when he was alive, and a performance by one of Korea’s most renowned singers, Jang Sa-ik. The program lasted over two and a half hours, but the audience’s attention never wavered.

With the arrival of summer, five volumes of poetry from the scheduled twenty-volume collected works of Seo Jeong-ju were published. A publication party and poetry recital was held at his alma mater, Dongguk University, to an audience of almost 600. World-renowned pianist Paik Kun-Woo and film actress Yoon Jeong-hee performed in the opening act, and the performance closed with a passionate musical performance of Seo’s beloved poem, “Blue Day” by the singer Song Chang-sik. A showcase of all the arts combined, Korea’s best theatrical performers, award-winning and veteran poets, singers, poetry performers, dancers, and invited foreign poets took part in showing the elegance of Korean culture.

The poet’s son, Seo Yoon, and his family came from America to take part and give thanks to the audience. Harvard professor David R. McCann was invited as a foreign poet to take part. When he took the stage, he explained his connection to Seo and showed a mechanical pencil he had received from him. He then recited a poem of his own that was about the pencil.

In autumn, as the chrysanthemums bloomed, a large scale 100th Anniversary Festival opened in Seo’s hometown. A variety of events such as literary seminars, an essay writing contest, a poetry recitation contest, a play, and the unveiling ceremony for a carved memorial stone were held from October 30th until the anniversary of the opening of the Midang Literary House on November 3rd. The next event after the autumn festival will be a memorial ceremony held in Seo Jeong-ju’s hometown to honor the day of his passing, December 23rd, two days before Christmas. This will include the publication of his collected works and a publication party, the publication of his previously unpublished poems, and the fourth and final seasonal performance.

* Article from the List Magazine published by the Literature Translation Institute of Korea