Short stories are like senten-...

01100010011010010110111001100001011100100111100100100000011001000110111101100101011100110110111000100111011101000010000001110111011011110111001001101011

Place yourself in a binary world where everything is either 1s or 0s, black or white. There's no nuance and no gray areas. If you land anywhere between 1 and 50, you fall into the 0 box. If you land anywhere between 51 and 100, you're all clumped together in the 1 box. Two categories; there is no in-between.

Then try to apply this 1-0 binary division to something as complex as humanity and to something as nuanced and subtle as existence. Put the whole rainbow of human emotion into one of only two boxes. Put every personality, every eccentric, every pair of lovers and every psychopath into only one of two boxes. Divide the whole world into two; only two. Divide the whole world into 1s and 0s, or, indeed, into “my” country and “your” country. This division can be brought forward into modern times by slicing the world into new and old, urban and countryside, parents and children, fog and sunshine, at peace and in pain.

At first, this may seem to be a simple division, like our right and left hands, like our men and our women, like our day and night. However, such judging and categorizing of the world into two groups lends itself to lazy thinking. These are dangerous divisions, as the round peg of existence cannot be forced into the square hole of our chosen categories. Like lava beneath Krakatoa, like suppressed emotions after a trauma, like tears after a break up, we begin to boil, soon to explode. We become Lear in the heath, clawing out our eyes because we have seen too much and cannot see enough.

This is the great dichotomous burden of existence and this is what Kim Seungok (김승옥, 金承鈺) (b. 1941) talks about in his two short stories "Record of a Journey to Mujin" (Oct. 1964) and "Seoul: 1964, Winter" (June 1965). The man was 22- and 23-years-old when these two short stories were published in the pages of World of Thought magazine (Sasangye, 사상계). His world of Seoul was in chaos. The soldiers had just seized power in 1961. The state was trying to finance favored industries. Cement and steel were about to leap forth from the rice paddies, and a new wave of young authors was sweeping across the literary fields of Seoul.

Kim's two short stories give us a brief glimpse at the Korean world of the mid-1960s. One is simply a tale about a man going back to his hometown for the week. The other covers a late-night string of drinks across Seoul in the middle of a cold winter. Those are both simple enough premises, perfect for that brief little window that is all that short stories can open onto our protagonists' lives. However, this short story window that Kim Seungok opens and then closes – allowing us to see a snapshot of his world, if but briefly – shows much more than just a trip home or a string of seedy bars. It shows the dichotomous burden of existence: we don't fit into simple categories.

Historical Times

Seoul of the mid-1960s was turbulent. The multi-layered fratricidal war had ended a decade or so earlier. A Red Scare, over a decade old, had been sweeping across South Korea. Concepts of nationalism were very closely tied to concepts of anti-Communism, tightly limiting the number of Korean voices that could be aired in society. Korea was still poor, not the rich nation we know today. It had lost any wealth it had accumulated between the 1920s and 1940s. The combination of war and kleptocracy ensured that.

One obstinate, corrupt, terrifying and paranoid elderly man in strict control of the government was kicked out of office in April 1960 by marches; marches largely led by students and professors. A short, tough peasant military officer came into office in 1961. His Supreme Council for National Reconstruction (국가재건최고회의, 國家再建最高會議) ran the country from 1961 to 1963. The country's first five-year economic plan was launched in 1962. In 1963, this military strongman took off his uniform and put on a suit, becoming "president". A Status of Forces Agreement was completed with the U.S. military in 1965. A treaty with Japan was passed in June 1965.

Back in Seoul, college and high school enrollment had quadrupled since the 1940s and 1950s. Most universities, and all of the good universities, were in Seoul. Every father across the nation dreamed of sending his son up to Seoul for a higher education. Daughters didn't even figure into the equation. The young male students were away from their parents and lived in cramped, ubiquitous boarding houses, hasuk-jip (하숙집), away from parental discipline and away from father's eye.

The universities didn't require a lot of their students; or, for that matter, of their professors. The universities were bursting at the seams and the professors had too many students in each class: they often skipped class as much as the students. In high school, students had already worked liked slaves. It's there that they got most of the education needed for a career, so they could slack off at university. However, they were sure to stay enrolled in university, especially in liberal arts or literature courses, and stay enrolled in grad schools, since jobs were few and far between. Seoul was still a relatively small town in the early and mid-1960s, and everyone seemed to know everyone.

These were the students and professors who led the marches that made one despot leave office. These were also the students and professors that the new strongman – from the lower classes, a peasant himself, short on words and long on measurable results – had to deal with as he solidified his control of the state.

Seoul politics of the late-1950s and mid-1960s was an elite affair, spurred on by this thin cream of university students and book-learned men. These students and well-read men played -- and play today, though less so, what with the expansion of education, the broadening of what it means to be “Korean” and more access to technology -- a special role in urban Korean society. Note that this is different from the dignity and valor that exists in the rough people who built modern Korea: the massive force of blue-collar laborers. This is a sort of "fake literati respect", or at least a "respect" that people are expected to voice, for people who use books as their primary weapons, as opposed to a screw driver or a welding machine.

This idle class of educated young men, with a strong sense of self-entitlement, sat around and discussed Great Things. Seoul had at the time an active and vibrant intellectual atmosphere. The two leading political and literature journals were Creation & Criticism (창작과 비평), which had a circulation of 18,000 in 1960, and World of Thought (사상계). We know World of Thought must have been good because it was frequently being shut down by the government. As historian Gregory Henderson notes, when Chang Myon (장면, 張勉) was prime minister in 1960 -- after the exile of Rhee and before Park launched his coup d'état -- one survey reported that there were 100,000 journalists in the country, most of them in Seoul. Everyone was reading and everyone was writing.

To congregate, all these men would meet in Seoul's "tea rooms." These were everything from bars to brothels to music halls to coffee shops, and these elite students would meet there to discuss every political rumor, every literary trend and every happening across the country, all with music, books, alcohol and prostitutes at easy reach. This led itself to the formation of clandestine student clubs, mostly political science or philosophy majors from the same campus and class. Take all these under-employed male students. Mix them in a growing political literary environment. Then add in all the "tea rooms" and small clubs. It was a heady mix, ready to explode.

As the new school year began in March 1960, the department of French literature at Seoul National University had a new freshman: the 19-year-old Kim Seungok. He was ripe with a political pen and bursting with a sharpened wit, ready to describe his times, word by word and line by line. In fact, as a student, Kim was a cartoonist at the Seoul Economic Daily and published his first well-known short story in 1962 in the Korea Daily newspaper (The Hankook-ilbo, 한국일보).

By 1964, as Kim Seungok was nearing the end of his undergrad, he published “Mujin”. His readers bought World of Thought to see, through his short stories, glimpses of the grand dichotomy. The newly installed police state was slowly tightening its grip on society, industrialization was trying to get launched, peace was made with Japan, and Korea was just on the cusp of beginning its final 20th century rollercoaster ride.

Dichotomy of Existence

Some say that to be Korean is quite burdensome. Indeed, it's questionable if people would actually choose to be Korean if they weren't tossed into it by the randomness of birth. Society here takes these new humans born onto the planet and through media, parents, school and military service, trains them how to be Korean. Humans are taught how to believe in the imagined community of Korea. The post-colonial globalized potpourri of cultures, tribes and peoples that developed in the late 20th century -- i.e., nationalism: that oh-so-modern 20th century religion -- makes it in some ways easier to be "Korean". You're just one more color in the rainbow. On the other hand, you are now faced with the question of how to be both Korean and global. Is wearing Hanbok all it takes to make you Korean? Does eating a hamburger make you not Korean?

Philosophers such as Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani (자말 압딘 알 아프가니), Liang Qichao (량 치차오, 양계초, 梁啓超) and Rabindranath Tagore (라빈드라나트 타고르) all asked many of the same questions. How do you keep your identity in a world created by and for the West? What is community, and how does it fit into a world of communities?

The way in which people see themselves as being Korean, and the way they think about this imagined community of Koreans, is at the core of Kim's two short stories. Who am I? What am I? Why am I here? Kim tries to sort this all out, with one main character traveling home to the countryside for a break, and with another main character drinking in a series of bars with his new friends on a cold winter night. Short stories are but brief glimpses into our lives.

Across Korean cinema and literature there are certain repeated axes: city/ country, mainland/ island, development/ underdevelopment, modern/ pre-modern, present/ past. This binary scale also shows itself when comparing the reputation of your hometown and the reputation of the other person's hometown; your elementary school and the other person's elementary school; your high school and the other person's high school; your university and the other person's university; your conscription military unit and the other person's conscription military unit. Moving into modern consumerism, it shows up in your handbag and the other person's handbag; your Swiss watch and the other person's Swiss watch; your imported car brand and the other person's imported car brand; your husband's employer and the other person's husband's employer; the year you started working at the large conglomerate and the year the other person started working at the large conglomerate; your child's elementary school and the other person's child's elementary school. The circle continues. Society continues. This can be seen first-hand in the brief short-story windows opened by Kim Seungok in 1964 and 1965. The burden of being Korean continues.

Kim Himself

Author Kim Seungok was 19-years-old when the chaos of the Second Republic bounded across South Korea. He was 20-years-old when the first modern coup d'état was launched. He was 23-years-old when he wrote the short story "Record of a Journey to Mujin". His debut had only been two years prior, in 1962. He was 24-years-old when he wrote “Seoul: 1964, Winter".

Like a hyacinth that bursts into bloom and then fades, Kim Seungok (b. 1941) wrote more than 10 short stories, essays, screenplays and novellas between the ages of 21 and 25, between 1962 and 1966. His stories burst to fame at the time from the pages of Seoul's newspapers and literary magazines, and most of his works are still read today. Kim led a wave of early and mid-'60s authors who were fed up with the prior dictator's arrogance and nervous about the new dictator's tightening grip. He wrote about rapid urbanization and the realities of living in these rapidly growing new cities. He wrote about how the human fits in between the city and the countryside, the modern and the past.

Writing was his forte. He captured the Zeitgeist of his times with his two most famous short stories. There are at least two versions of "Mujin" available in English, and both clock in at under 10,000 words and fewer than 54 pages.

The 1967 movie "Mist" ("Angae", "안개") is based on "Record of a Journey to Mujin". Kim Seungok himself worked on preparing the screenplay. The movie is available for viewing at YouTube in its entirety and with English subtitles at the KoreanFilm YouTube channel, a channel run by the Korean Film Archive and the Korean Classic Film Theater.

These are the only two of Kim's works that are commonly available in English. Asia Publishers puts out the "Bilingual Edition Modern Korean Literature", a series of thin, red-covered Korean short stories published on alternating pages in both Korean and English. “Mujin” was translated by Kevin O'Rourke and was published in 2012. The 75 short stories that make up the series are grouped into subjects, like "Division", "Love and Love Affairs" or "Taboo and Desire". "Mujin" is put in the "Industrialization" group.

To read "Seoul: 1964, Winter", head to Amazon and get the e-book of "Land of Exile: Contemporary Korean Fiction -- Expanded Edition". It was published in 2015 by Routledge and was translated and edited by Marshall R. Pihl, Bruce Fulton and Ju-Chan Fulton. The stories were originally published in Korea and in Korean between 1948 and 2004. Of the 16 stories included in the volume, the fifth is "Seoul: 1964, Winter" by Kim Seungok.

In the end, we are but a short glimpse onto this earth. Whether it's Chekhov, Hemingway or Kim Seungok, short stories give us a brief open window of understanding onto our characters' lives, and then the window is closed. We see the woman and her dog. We see a son and a father fishing. We see a man going back to his hometown to take a break. We don't get depth, we don't get Dickens, we don't get Dostoevsky, we don't get Dumas. A window opens. A window closes. We are born and then we die: that is the ultimate dichotomy.

0111010001101000011000010111010000100000011010010111001100100000011000010110110001101100

...-tences that are cut off half way through.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Asia Publishers, Namu Wiki, Routledge

gceaves@korea.kr

01100010011010010110111001100001011100100111100100100000011001000110111101100101011100110110111000100111011101000010000001110111011011110111001001101011

Place yourself in a binary world where everything is either 1s or 0s, black or white. There's no nuance and no gray areas. If you land anywhere between 1 and 50, you fall into the 0 box. If you land anywhere between 51 and 100, you're all clumped together in the 1 box. Two categories; there is no in-between.

Then try to apply this 1-0 binary division to something as complex as humanity and to something as nuanced and subtle as existence. Put the whole rainbow of human emotion into one of only two boxes. Put every personality, every eccentric, every pair of lovers and every psychopath into only one of two boxes. Divide the whole world into two; only two. Divide the whole world into 1s and 0s, or, indeed, into “my” country and “your” country. This division can be brought forward into modern times by slicing the world into new and old, urban and countryside, parents and children, fog and sunshine, at peace and in pain.

At first, this may seem to be a simple division, like our right and left hands, like our men and our women, like our day and night. However, such judging and categorizing of the world into two groups lends itself to lazy thinking. These are dangerous divisions, as the round peg of existence cannot be forced into the square hole of our chosen categories. Like lava beneath Krakatoa, like suppressed emotions after a trauma, like tears after a break up, we begin to boil, soon to explode. We become Lear in the heath, clawing out our eyes because we have seen too much and cannot see enough.

This is the great dichotomous burden of existence and this is what Kim Seungok (김승옥, 金承鈺) (b. 1941) talks about in his two short stories "Record of a Journey to Mujin" (Oct. 1964) and "Seoul: 1964, Winter" (June 1965). The man was 22- and 23-years-old when these two short stories were published in the pages of World of Thought magazine (Sasangye, 사상계). His world of Seoul was in chaos. The soldiers had just seized power in 1961. The state was trying to finance favored industries. Cement and steel were about to leap forth from the rice paddies, and a new wave of young authors was sweeping across the literary fields of Seoul.

Kim's two short stories give us a brief glimpse at the Korean world of the mid-1960s. One is simply a tale about a man going back to his hometown for the week. The other covers a late-night string of drinks across Seoul in the middle of a cold winter. Those are both simple enough premises, perfect for that brief little window that is all that short stories can open onto our protagonists' lives. However, this short story window that Kim Seungok opens and then closes – allowing us to see a snapshot of his world, if but briefly – shows much more than just a trip home or a string of seedy bars. It shows the dichotomous burden of existence: we don't fit into simple categories.

'Record of a Journey to Mujin' was originally published in Word of Thought magazine in October 1964. Asia Publishers put out a version in both Korean and English in 2012.

Historical Times

Seoul of the mid-1960s was turbulent. The multi-layered fratricidal war had ended a decade or so earlier. A Red Scare, over a decade old, had been sweeping across South Korea. Concepts of nationalism were very closely tied to concepts of anti-Communism, tightly limiting the number of Korean voices that could be aired in society. Korea was still poor, not the rich nation we know today. It had lost any wealth it had accumulated between the 1920s and 1940s. The combination of war and kleptocracy ensured that.

One obstinate, corrupt, terrifying and paranoid elderly man in strict control of the government was kicked out of office in April 1960 by marches; marches largely led by students and professors. A short, tough peasant military officer came into office in 1961. His Supreme Council for National Reconstruction (국가재건최고회의, 國家再建最高會議) ran the country from 1961 to 1963. The country's first five-year economic plan was launched in 1962. In 1963, this military strongman took off his uniform and put on a suit, becoming "president". A Status of Forces Agreement was completed with the U.S. military in 1965. A treaty with Japan was passed in June 1965.

Back in Seoul, college and high school enrollment had quadrupled since the 1940s and 1950s. Most universities, and all of the good universities, were in Seoul. Every father across the nation dreamed of sending his son up to Seoul for a higher education. Daughters didn't even figure into the equation. The young male students were away from their parents and lived in cramped, ubiquitous boarding houses, hasuk-jip (하숙집), away from parental discipline and away from father's eye.

The universities didn't require a lot of their students; or, for that matter, of their professors. The universities were bursting at the seams and the professors had too many students in each class: they often skipped class as much as the students. In high school, students had already worked liked slaves. It's there that they got most of the education needed for a career, so they could slack off at university. However, they were sure to stay enrolled in university, especially in liberal arts or literature courses, and stay enrolled in grad schools, since jobs were few and far between. Seoul was still a relatively small town in the early and mid-1960s, and everyone seemed to know everyone.

These were the students and professors who led the marches that made one despot leave office. These were also the students and professors that the new strongman – from the lower classes, a peasant himself, short on words and long on measurable results – had to deal with as he solidified his control of the state.

Seoul politics of the late-1950s and mid-1960s was an elite affair, spurred on by this thin cream of university students and book-learned men. These students and well-read men played -- and play today, though less so, what with the expansion of education, the broadening of what it means to be “Korean” and more access to technology -- a special role in urban Korean society. Note that this is different from the dignity and valor that exists in the rough people who built modern Korea: the massive force of blue-collar laborers. This is a sort of "fake literati respect", or at least a "respect" that people are expected to voice, for people who use books as their primary weapons, as opposed to a screw driver or a welding machine.

This idle class of educated young men, with a strong sense of self-entitlement, sat around and discussed Great Things. Seoul had at the time an active and vibrant intellectual atmosphere. The two leading political and literature journals were Creation & Criticism (창작과 비평), which had a circulation of 18,000 in 1960, and World of Thought (사상계). We know World of Thought must have been good because it was frequently being shut down by the government. As historian Gregory Henderson notes, when Chang Myon (장면, 張勉) was prime minister in 1960 -- after the exile of Rhee and before Park launched his coup d'état -- one survey reported that there were 100,000 journalists in the country, most of them in Seoul. Everyone was reading and everyone was writing.

To congregate, all these men would meet in Seoul's "tea rooms." These were everything from bars to brothels to music halls to coffee shops, and these elite students would meet there to discuss every political rumor, every literary trend and every happening across the country, all with music, books, alcohol and prostitutes at easy reach. This led itself to the formation of clandestine student clubs, mostly political science or philosophy majors from the same campus and class. Take all these under-employed male students. Mix them in a growing political literary environment. Then add in all the "tea rooms" and small clubs. It was a heady mix, ready to explode.

As the new school year began in March 1960, the department of French literature at Seoul National University had a new freshman: the 19-year-old Kim Seungok. He was ripe with a political pen and bursting with a sharpened wit, ready to describe his times, word by word and line by line. In fact, as a student, Kim was a cartoonist at the Seoul Economic Daily and published his first well-known short story in 1962 in the Korea Daily newspaper (The Hankook-ilbo, 한국일보).

By 1964, as Kim Seungok was nearing the end of his undergrad, he published “Mujin”. His readers bought World of Thought to see, through his short stories, glimpses of the grand dichotomy. The newly installed police state was slowly tightening its grip on society, industrialization was trying to get launched, peace was made with Japan, and Korea was just on the cusp of beginning its final 20th century rollercoaster ride.

Dichotomy of Existence

Some say that to be Korean is quite burdensome. Indeed, it's questionable if people would actually choose to be Korean if they weren't tossed into it by the randomness of birth. Society here takes these new humans born onto the planet and through media, parents, school and military service, trains them how to be Korean. Humans are taught how to believe in the imagined community of Korea. The post-colonial globalized potpourri of cultures, tribes and peoples that developed in the late 20th century -- i.e., nationalism: that oh-so-modern 20th century religion -- makes it in some ways easier to be "Korean". You're just one more color in the rainbow. On the other hand, you are now faced with the question of how to be both Korean and global. Is wearing Hanbok all it takes to make you Korean? Does eating a hamburger make you not Korean?

Philosophers such as Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani (자말 압딘 알 아프가니), Liang Qichao (량 치차오, 양계초, 梁啓超) and Rabindranath Tagore (라빈드라나트 타고르) all asked many of the same questions. How do you keep your identity in a world created by and for the West? What is community, and how does it fit into a world of communities?

The way in which people see themselves as being Korean, and the way they think about this imagined community of Koreans, is at the core of Kim's two short stories. Who am I? What am I? Why am I here? Kim tries to sort this all out, with one main character traveling home to the countryside for a break, and with another main character drinking in a series of bars with his new friends on a cold winter night. Short stories are but brief glimpses into our lives.

Across Korean cinema and literature there are certain repeated axes: city/ country, mainland/ island, development/ underdevelopment, modern/ pre-modern, present/ past. This binary scale also shows itself when comparing the reputation of your hometown and the reputation of the other person's hometown; your elementary school and the other person's elementary school; your high school and the other person's high school; your university and the other person's university; your conscription military unit and the other person's conscription military unit. Moving into modern consumerism, it shows up in your handbag and the other person's handbag; your Swiss watch and the other person's Swiss watch; your imported car brand and the other person's imported car brand; your husband's employer and the other person's husband's employer; the year you started working at the large conglomerate and the year the other person started working at the large conglomerate; your child's elementary school and the other person's child's elementary school. The circle continues. Society continues. This can be seen first-hand in the brief short-story windows opened by Kim Seungok in 1964 and 1965. The burden of being Korean continues.

Kim Himself

Author Kim Seungok was 19-years-old when the chaos of the Second Republic bounded across South Korea. He was 20-years-old when the first modern coup d'état was launched. He was 23-years-old when he wrote the short story "Record of a Journey to Mujin". His debut had only been two years prior, in 1962. He was 24-years-old when he wrote “Seoul: 1964, Winter".

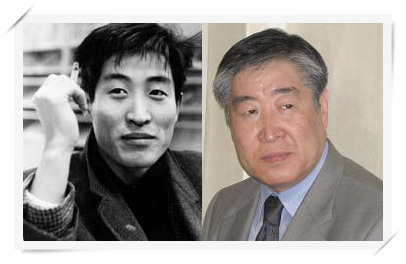

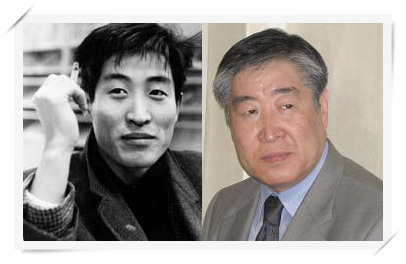

Kim Seungok was born in 1941 and is known for the short stories and other works he wrote in the mid-1960s. He is still widely read today.

Like a hyacinth that bursts into bloom and then fades, Kim Seungok (b. 1941) wrote more than 10 short stories, essays, screenplays and novellas between the ages of 21 and 25, between 1962 and 1966. His stories burst to fame at the time from the pages of Seoul's newspapers and literary magazines, and most of his works are still read today. Kim led a wave of early and mid-'60s authors who were fed up with the prior dictator's arrogance and nervous about the new dictator's tightening grip. He wrote about rapid urbanization and the realities of living in these rapidly growing new cities. He wrote about how the human fits in between the city and the countryside, the modern and the past.

Writing was his forte. He captured the Zeitgeist of his times with his two most famous short stories. There are at least two versions of "Mujin" available in English, and both clock in at under 10,000 words and fewer than 54 pages.

The 1967 movie "Mist" ("Angae", "안개") is based on "Record of a Journey to Mujin". Kim Seungok himself worked on preparing the screenplay. The movie is available for viewing at YouTube in its entirety and with English subtitles at the KoreanFilm YouTube channel, a channel run by the Korean Film Archive and the Korean Classic Film Theater.

These are the only two of Kim's works that are commonly available in English. Asia Publishers puts out the "Bilingual Edition Modern Korean Literature", a series of thin, red-covered Korean short stories published on alternating pages in both Korean and English. “Mujin” was translated by Kevin O'Rourke and was published in 2012. The 75 short stories that make up the series are grouped into subjects, like "Division", "Love and Love Affairs" or "Taboo and Desire". "Mujin" is put in the "Industrialization" group.

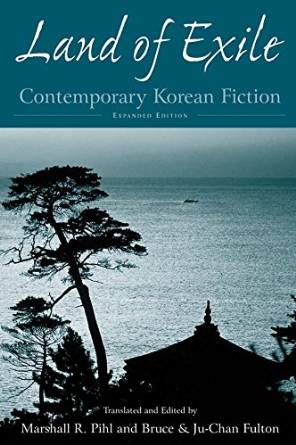

'Land of Exile' is published by Routledge in 2015. Kim Seungok's short story is the fifth one in the collection.

To read "Seoul: 1964, Winter", head to Amazon and get the e-book of "Land of Exile: Contemporary Korean Fiction -- Expanded Edition". It was published in 2015 by Routledge and was translated and edited by Marshall R. Pihl, Bruce Fulton and Ju-Chan Fulton. The stories were originally published in Korea and in Korean between 1948 and 2004. Of the 16 stories included in the volume, the fifth is "Seoul: 1964, Winter" by Kim Seungok.

In the end, we are but a short glimpse onto this earth. Whether it's Chekhov, Hemingway or Kim Seungok, short stories give us a brief open window of understanding onto our characters' lives, and then the window is closed. We see the woman and her dog. We see a son and a father fishing. We see a man going back to his hometown to take a break. We don't get depth, we don't get Dickens, we don't get Dostoevsky, we don't get Dumas. A window opens. A window closes. We are born and then we die: that is the ultimate dichotomy.

0111010001101000011000010111010000100000011010010111001100100000011000010110110001101100

...-tences that are cut off half way through.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Asia Publishers, Namu Wiki, Routledge

gceaves@korea.kr