For the longest time, when plowing through "The House With a Sunken Courtyard" ("마당깊은 집") I felt as if nothing was happening. It's an almost daily detailed description of the author's first year in Daegu in 1954 and 1955, living in poverty with his family in post-war urban savagery.

Author Kim Won-il, however, redeems himself with the closing pages, a sort of epilogue; an epilogue for his characters, an epilogue for the nation as a whole. The 46-year-old author, in 1988, calmly and assuredly recaps the two most-difficult years of his early teen-aged years, tying up all the loose ends, weaving closed the various character loops, and concluding with a passage that could sum up the entire 71-year-long-and-counting South Korean experiment:

"I stood there watching the scene, thinking to myself that my first year in Daegu was being buried under that earth [as the eponymous house undergoes construction]. It filled my heart with sorrow. At the same time, I was glad that my frequent hunger and sorrow would be buried under earth, too, never to reveal any trace. And a new two-story Western house was going to stand on it, as if to press my wretched memories into the earth for good." (p. 229)

That passage sums up the 71-year-long South Korean experiment. A Western standard, to which Korean society and all non-Western societies must change and adapt, can barely soothe the pains and traumas of the past, but it does. If there's one thing humans are good at, it's healing and moving on.

Just as modern South Korea uses a range of nationalist icons as soothing balms on the scars of history -- all the praising and self-assuredness one read's in the vernacular domestic press, for example -- the narrator in our tale, Gilnam, sees the construction of a Western-style house overtop his first house in Daegu as a sign of healing and of moving on.

"...we crossed the turbulent waters of those hard times together..." p. 12

From the start, however, I stand back and look at the world created by Kim Won-il. He wrote "The House With a Sunken Courtyard" in 1988 at the age of 46. He wrote it during the televised family reunions, during the lead-up to the Olympic Summer Games and during pro-democracy protests. The tale recounts life in Daegu in 1954 and 1955. Society was still mending after Korea's civil war, i.e., the Korean War: the war to determine what "Korea" would mean in the future. Daegu lay just inside the Busan Perimeter, so it remained technically unoccupied during the war, though the banks of the Nakdong River saw some of the bloodiest fighting, and political killings and revenge killings took place in Daegu straight through the mid-1950s. As a technically unoccupied city in 1950, therefore, it became home to many, many refugees who had fled southward. It was the first big city within the Busan Perimeter. Koreans from all over -- Gyeonggi-do Province, Hwanghae-do Province, Pyeongan-do Province, Hamgyeong-do Province and even Manchuria -- landed in Daegu, and it seems that a representative sample of them landed specifically in Kim's house with a sunken courtyard.

"...the black market area, the busiest section of the city..." p. 29

The house with a sunken courtyard that Kim Won-il recalls was home to four main families, all poor, plus the landlord's family and the house manager, Mrs. An. There was the Gyeonggi woman, her dentist son, the Pyeongyang woman, the head of the house, a jewelry store owner, a seamstress, the wounded veteran, the consumptive patient, the Gimcheon woman's son, the landlord's family, the Gyeonggi family, the Pyeongyang family, Junho's family and, among this post-war chaos, the family of Gilnam, our narrator, with his three younger siblings and his mother.

As Kim describes Daegu at the time, "...one could bump into refugees, bums, street vendors, porters, beggars, or shoeshine boys just as easily as one could kick away a stray stone while walking on an unpaved road." (p. 7) The house with a sunken courtyard had at least one of each, plus some.

"...You must grow up. You must grow up fast and become a man. That's the only way I can leave behind these humiliations..." p. 140

It seems entirely possible that all those vaguely similar Korean soap operas -- all those widely popular telenovelas that are churned out every season by the likes of KBS, SBS and MBC -- have their root in the tale woven by Kim in "The House With a Sunken Courtyard". In his storm-tossed tale of Korea in the middle of the 1950s, Kim recounts the trials and tribulations of this expansive household: the rich landlords, the jewelry shop, the middle-class families, baking rolls, the poor families, sharing the outhouse, falling in love, chopping wood, going to the U.S. to study, Communist sympathizers, marrying off one's daughter, seeing Western Christmas parties for the first time, corrupt government officials, learning there's a difference between "modern" and "Korean", creating what a "modern Korea" should be, secret police, agents provocateurs, falling in love with a U.S. military officer, failing middle school exams, and even delivering newspapers. Yet nothing happens. Absolutely nothing happens in the tale, and yet everything happens.

It seems entirely possible that all those vaguely similar Korean soap operas -- all those widely popular telenovelas that are churned out every season by the likes of KBS, SBS and MBC -- have their root in the tale woven by Kim in "The House With a Sunken Courtyard". In his storm-tossed tale of Korea in the middle of the 1950s, Kim recounts the trials and tribulations of this expansive household: the rich landlords, the jewelry shop, the middle-class families, baking rolls, the poor families, sharing the outhouse, falling in love, chopping wood, going to the U.S. to study, Communist sympathizers, marrying off one's daughter, seeing Western Christmas parties for the first time, corrupt government officials, learning there's a difference between "modern" and "Korean", creating what a "modern Korea" should be, secret police, agents provocateurs, falling in love with a U.S. military officer, failing middle school exams, and even delivering newspapers. Yet nothing happens. Absolutely nothing happens in the tale, and yet everything happens.

In terms of social commentary, you can see many aspects of today's Korea in Kim's mid-1950s Korea. Physical cement and infrastructure has changed, but humans require a bit more time. In the tale, readers repeatedly see the prevalence of a strictly stratified society, a society that judges everyone based on every possible factor, of fierce sexism and of Trump-like racism: it's spoken to your face with no shame. Similarly, if you open a newspaper or read the literature of modern South Korea today, you see the class divisions, the sexism and the ever-present racism, but at least the sewage systems, telephone lines, roads and architecture have changed.

For example, Kim describes one scene toward the end of the book. A young woman who also resides in the house with a sunken courtyard is driven back home by her future husband and his driver. "An American military jeep that had been rushing towards us with brightly lit headlights stopped at the lane's entrance. The driver was a black soldier. Miseon, who was wearing a red muffler and had a shoulder bag dangling from her shoulder, got out of the jeep from the rear seat, and an American officer who had been sitting beside her on the rear seat also got off. It was the same American officer who had been a guest at the Christmas Eve party. The couple stood face to face at the entrance of the lane and exchanged a few words in English. The American officer draped his arm around Miseon's slender waist."

"The children who had been playing hide-and-seek hurled insults at the American officer and Miseon before running off giggling. "Swala Swala. [Yankee speak! Yankee speak!] Chewing gum give me." "Americans big nose. Americans big ass." "It's an American whore. American whores suck American cocks." (p. 196) Alas, this writer has been subject to similar comments and has directly witnessed others being subjected to it, too. So, the racism -- solely directly at Korean women, oddly enough, never at Korean men -- as described in 1954 still exists quite prominently in modern South Korea.

As for sexism, well, the examples are too many to list.

"...You'll make an excellent wife. You're hard-working and tender-hearted, so you'll take good care of your husband and manage the household well..." p. 155

Nonetheless, the story is one of life, and here I must issue a spoilers warning. Looming over the entire tale, and coming to us in the epilogue, is the saddening, moving death of Gilnam's younger brother, Gilsu. Kim's two other siblings survive. We hear about their success in the last few pages. Yet the death of the youngest sibling is quite moving. Gilsu, "...who had warmed up my winter nights like a puppy or a kitten survived the cruel influenza of that winter to live three more years, but died with the 'dirty time,' before our family was able to shake off poverty. Because of his uncertain gait and pronunciation, he was refused admission to primary school and died one cold winter night of meningitis, at age eight, without ever having had the benefit of hospital care." (p. 216) That line -- "before our family was able to shake off poverty" -- sums up the modern South Korean experiment better than any number of government-issued press releases or glossy promotional videos. That line is Korea.

On a more cheerful note, Kim includes one of the most believable lines of all time when he described the Gyeonggi woman's reaction to seeing a Western-style buffet for the first time: "What a barbaric way of eating! To eat standing up and talking and giggling! I wouldn't know what any of the food tasted like." (p. 174) It seems that the strength and confidence of a middle-aged, married Korean woman was as formidable in 1954 as it is in 2016.

Originally published in 1988, "The House With a Sunken Courtyard" was translated into English in 2013 by Suh Ji-moon, and was put out by the Dalkey Archive with support from the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea). Typos occur less frequently in this story than in other LTI Korea publications in English, but they are still too common for the book to be considered truly professional.

In sum, "The House With a Sunken Courtyard" falls into the broad category of LTI Korea-published books that are reminisces of an elderly or middle-aged person's youth in either colonial Korea, war-torn Korea or post-war Korea. It's a heartwarming snippet of Daegu in 1954 and 1955, and upon reading it you're quite sure that the author, Kim Won-il, would be an honest friend and a great dinner guest. The tales he weaves are wonderful.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: the Literature Translation Institute of Korea

gceaves@korea.kr

Author Kim Won-il, however, redeems himself with the closing pages, a sort of epilogue; an epilogue for his characters, an epilogue for the nation as a whole. The 46-year-old author, in 1988, calmly and assuredly recaps the two most-difficult years of his early teen-aged years, tying up all the loose ends, weaving closed the various character loops, and concluding with a passage that could sum up the entire 71-year-long-and-counting South Korean experiment:

"I stood there watching the scene, thinking to myself that my first year in Daegu was being buried under that earth [as the eponymous house undergoes construction]. It filled my heart with sorrow. At the same time, I was glad that my frequent hunger and sorrow would be buried under earth, too, never to reveal any trace. And a new two-story Western house was going to stand on it, as if to press my wretched memories into the earth for good." (p. 229)

That passage sums up the 71-year-long South Korean experiment. A Western standard, to which Korean society and all non-Western societies must change and adapt, can barely soothe the pains and traumas of the past, but it does. If there's one thing humans are good at, it's healing and moving on.

'The House With a Sunken Courtyard' was written in 1988 by Kim Won-il and translated into English in 2013.

Just as modern South Korea uses a range of nationalist icons as soothing balms on the scars of history -- all the praising and self-assuredness one read's in the vernacular domestic press, for example -- the narrator in our tale, Gilnam, sees the construction of a Western-style house overtop his first house in Daegu as a sign of healing and of moving on.

"...we crossed the turbulent waters of those hard times together..." p. 12

From the start, however, I stand back and look at the world created by Kim Won-il. He wrote "The House With a Sunken Courtyard" in 1988 at the age of 46. He wrote it during the televised family reunions, during the lead-up to the Olympic Summer Games and during pro-democracy protests. The tale recounts life in Daegu in 1954 and 1955. Society was still mending after Korea's civil war, i.e., the Korean War: the war to determine what "Korea" would mean in the future. Daegu lay just inside the Busan Perimeter, so it remained technically unoccupied during the war, though the banks of the Nakdong River saw some of the bloodiest fighting, and political killings and revenge killings took place in Daegu straight through the mid-1950s. As a technically unoccupied city in 1950, therefore, it became home to many, many refugees who had fled southward. It was the first big city within the Busan Perimeter. Koreans from all over -- Gyeonggi-do Province, Hwanghae-do Province, Pyeongan-do Province, Hamgyeong-do Province and even Manchuria -- landed in Daegu, and it seems that a representative sample of them landed specifically in Kim's house with a sunken courtyard.

"...the black market area, the busiest section of the city..." p. 29

The house with a sunken courtyard that Kim Won-il recalls was home to four main families, all poor, plus the landlord's family and the house manager, Mrs. An. There was the Gyeonggi woman, her dentist son, the Pyeongyang woman, the head of the house, a jewelry store owner, a seamstress, the wounded veteran, the consumptive patient, the Gimcheon woman's son, the landlord's family, the Gyeonggi family, the Pyeongyang family, Junho's family and, among this post-war chaos, the family of Gilnam, our narrator, with his three younger siblings and his mother.

As Kim describes Daegu at the time, "...one could bump into refugees, bums, street vendors, porters, beggars, or shoeshine boys just as easily as one could kick away a stray stone while walking on an unpaved road." (p. 7) The house with a sunken courtyard had at least one of each, plus some.

"...You must grow up. You must grow up fast and become a man. That's the only way I can leave behind these humiliations..." p. 140

Kim Won-il wrote 'The House With a Sunken Courtyard' in 1988.

In terms of social commentary, you can see many aspects of today's Korea in Kim's mid-1950s Korea. Physical cement and infrastructure has changed, but humans require a bit more time. In the tale, readers repeatedly see the prevalence of a strictly stratified society, a society that judges everyone based on every possible factor, of fierce sexism and of Trump-like racism: it's spoken to your face with no shame. Similarly, if you open a newspaper or read the literature of modern South Korea today, you see the class divisions, the sexism and the ever-present racism, but at least the sewage systems, telephone lines, roads and architecture have changed.

For example, Kim describes one scene toward the end of the book. A young woman who also resides in the house with a sunken courtyard is driven back home by her future husband and his driver. "An American military jeep that had been rushing towards us with brightly lit headlights stopped at the lane's entrance. The driver was a black soldier. Miseon, who was wearing a red muffler and had a shoulder bag dangling from her shoulder, got out of the jeep from the rear seat, and an American officer who had been sitting beside her on the rear seat also got off. It was the same American officer who had been a guest at the Christmas Eve party. The couple stood face to face at the entrance of the lane and exchanged a few words in English. The American officer draped his arm around Miseon's slender waist."

"The children who had been playing hide-and-seek hurled insults at the American officer and Miseon before running off giggling. "Swala Swala. [Yankee speak! Yankee speak!] Chewing gum give me." "Americans big nose. Americans big ass." "It's an American whore. American whores suck American cocks." (p. 196) Alas, this writer has been subject to similar comments and has directly witnessed others being subjected to it, too. So, the racism -- solely directly at Korean women, oddly enough, never at Korean men -- as described in 1954 still exists quite prominently in modern South Korea.

As for sexism, well, the examples are too many to list.

"...You'll make an excellent wife. You're hard-working and tender-hearted, so you'll take good care of your husband and manage the household well..." p. 155

Nonetheless, the story is one of life, and here I must issue a spoilers warning. Looming over the entire tale, and coming to us in the epilogue, is the saddening, moving death of Gilnam's younger brother, Gilsu. Kim's two other siblings survive. We hear about their success in the last few pages. Yet the death of the youngest sibling is quite moving. Gilsu, "...who had warmed up my winter nights like a puppy or a kitten survived the cruel influenza of that winter to live three more years, but died with the 'dirty time,' before our family was able to shake off poverty. Because of his uncertain gait and pronunciation, he was refused admission to primary school and died one cold winter night of meningitis, at age eight, without ever having had the benefit of hospital care." (p. 216) That line -- "before our family was able to shake off poverty" -- sums up the modern South Korean experiment better than any number of government-issued press releases or glossy promotional videos. That line is Korea.

On a more cheerful note, Kim includes one of the most believable lines of all time when he described the Gyeonggi woman's reaction to seeing a Western-style buffet for the first time: "What a barbaric way of eating! To eat standing up and talking and giggling! I wouldn't know what any of the food tasted like." (p. 174) It seems that the strength and confidence of a middle-aged, married Korean woman was as formidable in 1954 as it is in 2016.

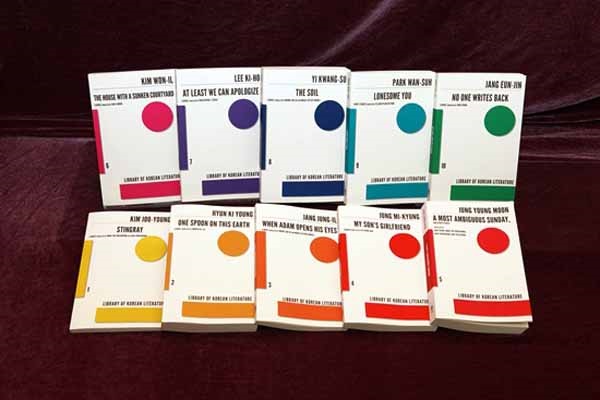

The Dalkey Archive, with support from the Literature Translation Institute of Korea, puts out the Library of Korean Literature.

Originally published in 1988, "The House With a Sunken Courtyard" was translated into English in 2013 by Suh Ji-moon, and was put out by the Dalkey Archive with support from the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea). Typos occur less frequently in this story than in other LTI Korea publications in English, but they are still too common for the book to be considered truly professional.

In sum, "The House With a Sunken Courtyard" falls into the broad category of LTI Korea-published books that are reminisces of an elderly or middle-aged person's youth in either colonial Korea, war-torn Korea or post-war Korea. It's a heartwarming snippet of Daegu in 1954 and 1955, and upon reading it you're quite sure that the author, Kim Won-il, would be an honest friend and a great dinner guest. The tales he weaves are wonderful.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: the Literature Translation Institute of Korea

gceaves@korea.kr