Picture a novel like Camus' "The Stranger" (1942). It would touch on the absurdity of life and existentialism, as man wanders through life, through relationships, through funerals, through murders, through deaths.

Picture a novel like Kafka's "The Trial" (1925). It would touch on the brevity of our existence, the revolving wheel of processes that govern our day-to-day life, the meaninglessness of those processes, the meaninglessness of our day-to-day happenings, and our utter lack of control in the grander scheme of things.

Picture a novel like Bulgakov's "The Master and Margarita" (1967). It would touch on one long satirical conversation with death, a man on a park bench talking to the devil, ripping society apart with satire and mockery.

Or perhaps, even, picture a novel like Gogol's "Dead Souls" (1842). It would touch on the flaws and faults of the author's society, both capitalist and communist, corrupt politicians, lying idealists, a rigged system, a shrug of the shoulders as you realize that the world around you is insane.

Each of the above four ingredients are brought together to cook a delicious dish, Choi In-hun's "The Square" (November 1960, in the pages of Dawn, a literature magazine). Written when the author was 24-years-old, amid modern-day South Korea's own year of living dangerously, as revolutions and coup d'états stormed the streets of Seoul, "The Square" is a young man's conversation with himself, asking the big questions about life, the universe and everything.

"There's nothing extraordinary about it, Myong-jun. They have no choice but to live." (p.65)

Less of a novel and

more of a treatise, "The Square" follows Lee Myong-jun as he tries to figure out what life is all about, why we are here and what's the best way to lead a life. He's in South Korea. He's with one woman. He's in North Korea. He's with another woman. Then he departs for distant shores, shores that we all will eventually see but which we cannot see at the moment.

Before we continue, however, a note on the translation. The translator here chose the title "The Square." However, a better choice would have been "The Agora" if you're feeling Greek, or "The Forum" if you're feeling more Roman. Maybe even "The Plaza," if you prefer. The original Korean title, 광장/ 廣場, implies an open public space where debate can take place. This nuance -- of a conversation, an interaction between humans, my personal space and the public space -- is much stronger in words like "agora" or "forum" than it is in "square."

The key quote concerning this discourse between the personal space and the public space comes on page 42 -- of a 147-page book -- during a conversation between our protagonist, Lee Myong-jun, and his friend Mr. Chung. (Here, I use the word "Agora" as opposed to "Square".) Choi writes, "Mankind cannot live in a closed room. Mankind belongs to the Agora. Politics is the most unredeemed place in the Agora of mankind. In Western countries, Christian churches assume a role like holy water purifying politics, absolving it of its sins... Especially in Korea's political Agora, excrement and garbage have just piled up. Things that should be everyone's are selfishly taken for personal benefit. Roadside flowers are picked from the ground and put in flowerpots at home, public faucets are extracted only to be put in the bathroom of a private home, or a pavement is dug up to be used as a kitchen floor."

The human body is probably the shadow of loneliness cast by spatial emptiness... Life is the son of loneliness who cannot learn forgotten things. (p. 70)

The quote is quite long. It goes on for three pages. Mr. Chung asks Myong-jun about politics, and he launches a diatribe -- more like a soliloquy, to be honest -- for three pages. Mr. Chung asks him on page 42, "What about jumping into politics?" Three pages later, author Choi finishes Myong-jun's soliloquy by saying, "The answer to the riddle is a paradox. It is that the good father and the bad public figure are the same person. No one remains in the Agora. When the necessary plundering and fraud end, the Agora is empty. The Agora is dead. Is this not South Korea?" (p. 44)

Interestingly enough, this diatribe comes immediately after Myong-jun is shown an actual mummy from ancient Egypt, a recently acquired new possession of Mr. Chung. With imagery as blunt as that used by Mary Shelley in "Frankenstein " (1818), or as blunt as that used by Bulgakov in "The Master and Margarita" (1967), author Choi has his character Myong-jun -- literally -- stare death in the face. What can remind a 24-year-old author of death more than an entombed human body?

"It is a big mistake when one person assumes that one understands the other. A person can only understand oneself." (p. 64)

As Myong-jun figures out life, he falls in love, walks around Seoul, is interrogated by the police, feels guilt about sex and love, is unimpressed by existence in the South, sneaks into North Korea, becomes a writer for a communist mouthpiece, falls in love, is interrogated by communist party members, feels guilt about sex and love, is unimpressed by existence in the North, gets sent southward in the Korean War, meets his love again on the battlefield, ends up in a POW camp for North Korean and Chinese soldiers captured by the U.S. and U.N. troops, calls out five times, "I want a neutral country!" to both the communists and the capitalists, befriends an Indian captain, sees the beauty of Victoria Harbour at night, and then fades away into a watery sunset. Moving, human, emotional, expansive, a positively-minded reader would think that he achieves happiness in the end.

The distinctive dusk of Manchuria was so breathtaking that it gave the impression that the whole world was immersed in a magnificent sea of fire. (p.90)

By page 93, our protagonist had fled to North Korea, partially out of guilt for having had sex, but mostly just to seek out a new Agora; a new space for existence. With dreams of revolutionary fervor, passion for the people, and a stirring body politic, he lands in South Korea's communist brother-nation... and his dreams are shattered. There was no Agora in the North.

"What Myong-jun discovered in North Korea was an ash-gray republic. It was not a republic that lived in the excitement of revolution, passionately burning blood-red like the Manchurian sunset. What surprised him more was that the communists did not want excitement or passion. The first time he had clearly felt the inner life of this society was when he was traveling around the major cities of North Korea on a lecture tour by order of the party just after he had gone north. Schools, factories, citizens halls; the faces filling these places were, in a word, lifeless. They simply sat with passive obedience. There was no expression or emotion on their faces. They were not the ardent faces of citizens living in a revolutionary republic." (p. 93)

Reading "The Square" in 2016, and reading the description of North Korea written in 1960, it crosses the mind that it has been 71 years since modern Korea -- North and South -- got its independence. It has been 68 years since both the Pyongyang and Seoul governments were formed, under the auspices of both the USSR and the USA. It has been 63 years since the end of the Korean War (1950-1953). It has been 44 years since South Korea's economic growth really started to take off with the Third Five-year Plan (1972-1976). It has been 20 years since South Korea joined the OECD. Author Choi In-hun's description of North Korea is just as true now as it was then.

If there truly is only "one Korea," as both governments in Seoul and Pyongyang profess to believe, and if both lay claim to be the inheritor of colonial Korea, then this presents South Korea with a conundrum. On the one hand, between the two, Seoul is the only moral government. For all its faults, the Seoul government is the only option when choosing between Seoul and Pyongyang. Then, however, like Coleridge's albatross of yore, North Korea's human rights violations hangs like a yoke around the neck of South Korea. It is Seoul's moral duty to take up the cause of saving the North Korean people from their oppressor. Not only would this heal some of the wounds that the South Korean government itself has committed over the years, it would also help to fix that other great out-of-balance result of 1945-1949: the communist government in Beijing and a democratic Taiwan.

"This was a society in which private desires were taboo. This code of taboo heavily cloaked the air of North Korean society. The party imposed a yoke and whip on the people as if they were cows plowing a filed. They were not farmers but domesticated animals. When they ran because the party said to run, it was done with minimal effort. When there was no prize for the winner, who would want to run wholeheartedly? The people were just hoping that someday their yoke would turn into a magic wand that would bring them freedom and fortune. In the Agora of North Korea, there were no people. There were only marionettes." (p. 105)

"Formality and the complications of exquisite etiquette seemed annoying and meaningless in a battleground. Living every day, face-to-face with the dark shadow of death, they groped in their bodies for the power that could dispel their unease and distress." (p.128)

Choi In-hun's tale, however, steers clear of geopolitics and sticks to the human: to the utterly human. We are inside Myong-jun's mind, with his feelings, his questions about life and his desires. In the end, he calls out, "A neutral country!" five times -- choosing an Agora of his own -- which, at the end of the novel, loops back to the opening of the novel on board the POW refugee ship steaming through the South China Sea.

"A neutral country. A place where you will be a total stranger. A place where you can hang around all day in the streets and no one touches your shoulder to say "Hi!" A place where no one knows or wants to know who you are and what you are. Myong-jun's heart leaped at the thought. The future was tantalizing as he fantasized about his anonymity." (p. 145)

In the end, Myong-jun was free. Free in his own personal room and free from the existential Agora.

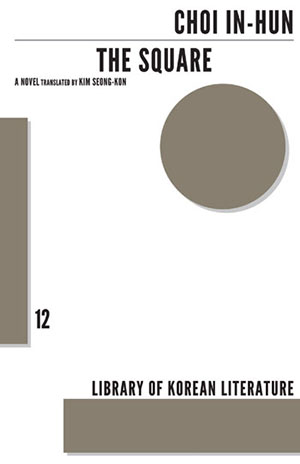

Footnote: Choi In-hun was born in 1936. He wrote "The Square" in November 1960 at the age of 24. It was published in the pages of Dawn, a literature magazine. "The Square" won the Dong-in Literature Award in 1966. The Dalkey Archive put out an English version of "The Square" in 2014, with help from both the Illinois Arts Council Agency and the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea), and it was translated by Kim Seong-kon, current president of the LTI Korea.

by Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Literature Translation Institute of Korea

gceaves@korea.kr

Picture a novel like Kafka's "The Trial" (1925). It would touch on the brevity of our existence, the revolving wheel of processes that govern our day-to-day life, the meaninglessness of those processes, the meaninglessness of our day-to-day happenings, and our utter lack of control in the grander scheme of things.

Picture a novel like Bulgakov's "The Master and Margarita" (1967). It would touch on one long satirical conversation with death, a man on a park bench talking to the devil, ripping society apart with satire and mockery.

Or perhaps, even, picture a novel like Gogol's "Dead Souls" (1842). It would touch on the flaws and faults of the author's society, both capitalist and communist, corrupt politicians, lying idealists, a rigged system, a shrug of the shoulders as you realize that the world around you is insane.

Each of the above four ingredients are brought together to cook a delicious dish, Choi In-hun's "The Square" (November 1960, in the pages of Dawn, a literature magazine). Written when the author was 24-years-old, amid modern-day South Korea's own year of living dangerously, as revolutions and coup d'états stormed the streets of Seoul, "The Square" is a young man's conversation with himself, asking the big questions about life, the universe and everything.

"There's nothing extraordinary about it, Myong-jun. They have no choice but to live." (p.65)

Less of a novel and

'The Square' was originally published in the pages of Dawn, a literature magazine, in November 1960, South Korea's own year of living dangerously.

Before we continue, however, a note on the translation. The translator here chose the title "The Square." However, a better choice would have been "The Agora" if you're feeling Greek, or "The Forum" if you're feeling more Roman. Maybe even "The Plaza," if you prefer. The original Korean title, 광장/ 廣場, implies an open public space where debate can take place. This nuance -- of a conversation, an interaction between humans, my personal space and the public space -- is much stronger in words like "agora" or "forum" than it is in "square."

The key quote concerning this discourse between the personal space and the public space comes on page 42 -- of a 147-page book -- during a conversation between our protagonist, Lee Myong-jun, and his friend Mr. Chung. (Here, I use the word "Agora" as opposed to "Square".) Choi writes, "Mankind cannot live in a closed room. Mankind belongs to the Agora. Politics is the most unredeemed place in the Agora of mankind. In Western countries, Christian churches assume a role like holy water purifying politics, absolving it of its sins... Especially in Korea's political Agora, excrement and garbage have just piled up. Things that should be everyone's are selfishly taken for personal benefit. Roadside flowers are picked from the ground and put in flowerpots at home, public faucets are extracted only to be put in the bathroom of a private home, or a pavement is dug up to be used as a kitchen floor."

The human body is probably the shadow of loneliness cast by spatial emptiness... Life is the son of loneliness who cannot learn forgotten things. (p. 70)

The quote is quite long. It goes on for three pages. Mr. Chung asks Myong-jun about politics, and he launches a diatribe -- more like a soliloquy, to be honest -- for three pages. Mr. Chung asks him on page 42, "What about jumping into politics?" Three pages later, author Choi finishes Myong-jun's soliloquy by saying, "The answer to the riddle is a paradox. It is that the good father and the bad public figure are the same person. No one remains in the Agora. When the necessary plundering and fraud end, the Agora is empty. The Agora is dead. Is this not South Korea?" (p. 44)

Interestingly enough, this diatribe comes immediately after Myong-jun is shown an actual mummy from ancient Egypt, a recently acquired new possession of Mr. Chung. With imagery as blunt as that used by Mary Shelley in "Frankenstein " (1818), or as blunt as that used by Bulgakov in "The Master and Margarita" (1967), author Choi has his character Myong-jun -- literally -- stare death in the face. What can remind a 24-year-old author of death more than an entombed human body?

"It is a big mistake when one person assumes that one understands the other. A person can only understand oneself." (p. 64)

As Myong-jun figures out life, he falls in love, walks around Seoul, is interrogated by the police, feels guilt about sex and love, is unimpressed by existence in the South, sneaks into North Korea, becomes a writer for a communist mouthpiece, falls in love, is interrogated by communist party members, feels guilt about sex and love, is unimpressed by existence in the North, gets sent southward in the Korean War, meets his love again on the battlefield, ends up in a POW camp for North Korean and Chinese soldiers captured by the U.S. and U.N. troops, calls out five times, "I want a neutral country!" to both the communists and the capitalists, befriends an Indian captain, sees the beauty of Victoria Harbour at night, and then fades away into a watery sunset. Moving, human, emotional, expansive, a positively-minded reader would think that he achieves happiness in the end.

The distinctive dusk of Manchuria was so breathtaking that it gave the impression that the whole world was immersed in a magnificent sea of fire. (p.90)

Choi In -hun was born in 1936 and published 'The Square' at the age of 24 in 1960.

By page 93, our protagonist had fled to North Korea, partially out of guilt for having had sex, but mostly just to seek out a new Agora; a new space for existence. With dreams of revolutionary fervor, passion for the people, and a stirring body politic, he lands in South Korea's communist brother-nation... and his dreams are shattered. There was no Agora in the North.

"What Myong-jun discovered in North Korea was an ash-gray republic. It was not a republic that lived in the excitement of revolution, passionately burning blood-red like the Manchurian sunset. What surprised him more was that the communists did not want excitement or passion. The first time he had clearly felt the inner life of this society was when he was traveling around the major cities of North Korea on a lecture tour by order of the party just after he had gone north. Schools, factories, citizens halls; the faces filling these places were, in a word, lifeless. They simply sat with passive obedience. There was no expression or emotion on their faces. They were not the ardent faces of citizens living in a revolutionary republic." (p. 93)

Reading "The Square" in 2016, and reading the description of North Korea written in 1960, it crosses the mind that it has been 71 years since modern Korea -- North and South -- got its independence. It has been 68 years since both the Pyongyang and Seoul governments were formed, under the auspices of both the USSR and the USA. It has been 63 years since the end of the Korean War (1950-1953). It has been 44 years since South Korea's economic growth really started to take off with the Third Five-year Plan (1972-1976). It has been 20 years since South Korea joined the OECD. Author Choi In-hun's description of North Korea is just as true now as it was then.

If there truly is only "one Korea," as both governments in Seoul and Pyongyang profess to believe, and if both lay claim to be the inheritor of colonial Korea, then this presents South Korea with a conundrum. On the one hand, between the two, Seoul is the only moral government. For all its faults, the Seoul government is the only option when choosing between Seoul and Pyongyang. Then, however, like Coleridge's albatross of yore, North Korea's human rights violations hangs like a yoke around the neck of South Korea. It is Seoul's moral duty to take up the cause of saving the North Korean people from their oppressor. Not only would this heal some of the wounds that the South Korean government itself has committed over the years, it would also help to fix that other great out-of-balance result of 1945-1949: the communist government in Beijing and a democratic Taiwan.

"This was a society in which private desires were taboo. This code of taboo heavily cloaked the air of North Korean society. The party imposed a yoke and whip on the people as if they were cows plowing a filed. They were not farmers but domesticated animals. When they ran because the party said to run, it was done with minimal effort. When there was no prize for the winner, who would want to run wholeheartedly? The people were just hoping that someday their yoke would turn into a magic wand that would bring them freedom and fortune. In the Agora of North Korea, there were no people. There were only marionettes." (p. 105)

"Formality and the complications of exquisite etiquette seemed annoying and meaningless in a battleground. Living every day, face-to-face with the dark shadow of death, they groped in their bodies for the power that could dispel their unease and distress." (p.128)

Choi In-hun's tale, however, steers clear of geopolitics and sticks to the human: to the utterly human. We are inside Myong-jun's mind, with his feelings, his questions about life and his desires. In the end, he calls out, "A neutral country!" five times -- choosing an Agora of his own -- which, at the end of the novel, loops back to the opening of the novel on board the POW refugee ship steaming through the South China Sea.

"A neutral country. A place where you will be a total stranger. A place where you can hang around all day in the streets and no one touches your shoulder to say "Hi!" A place where no one knows or wants to know who you are and what you are. Myong-jun's heart leaped at the thought. The future was tantalizing as he fantasized about his anonymity." (p. 145)

In the end, Myong-jun was free. Free in his own personal room and free from the existential Agora.

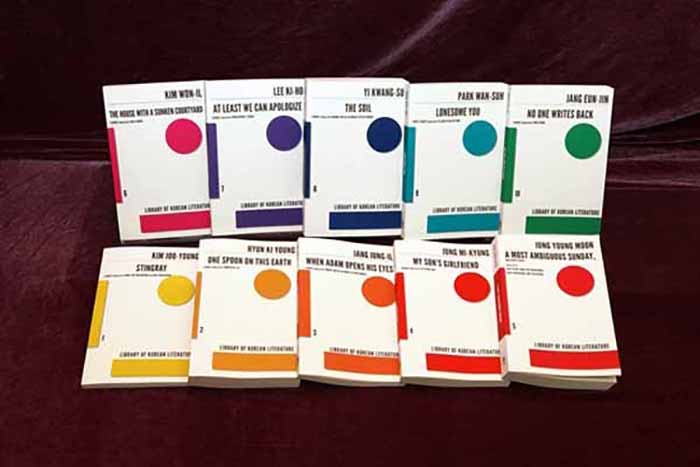

The LTI Korea helps Dalkey Press to put out a whole range of Korean books in English.

Footnote: Choi In-hun was born in 1936. He wrote "The Square" in November 1960 at the age of 24. It was published in the pages of Dawn, a literature magazine. "The Square" won the Dong-in Literature Award in 1966. The Dalkey Archive put out an English version of "The Square" in 2014, with help from both the Illinois Arts Council Agency and the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea), and it was translated by Kim Seong-kon, current president of the LTI Korea.

by Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: Literature Translation Institute of Korea

gceaves@korea.kr