View this article in another language

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

A dark, dark pall hangs over modern-day South Korea, and it's not the atrocities being committed in North Korea, as unlikely as that may sound. This dark pall is much more consumerist and much more industrial than any horrors taking place north of the 38th parallel.

This pall is the soulless emptiness that comes from a loss of faith in the South Korean Dream. It comes from a lack of trust in the generation born in the 1940s and 1950s and a lack of trust in what they built; in the wealth they crafted out of nothing. The pall comes from a lack of nature, trees and parks all across the country: too many people, not enough greenery. The pall comes from too many humans living in too little space, with no space for the human soul. There's no room to turn at school. There's no space in society for non-mainstream voices. There's no physical space across the nation and no political space within domestic politics to spread your wings and to fly. Add to this a dictatorship massacring democracy activists in May 1980.

This wave of malaise is represented across modern day South Korea through its most representative forms of art: indie music, animation and online comic strips, TV soap opera scripts and, most importantly, literature.

The wave of young South Korean authors who were born in the 1960s, more or less, and who came of age in the 1990s, more or less, are exemplary of this dark wave of depression and lack of faith. They're also some of the best author-psychoanalysts around.

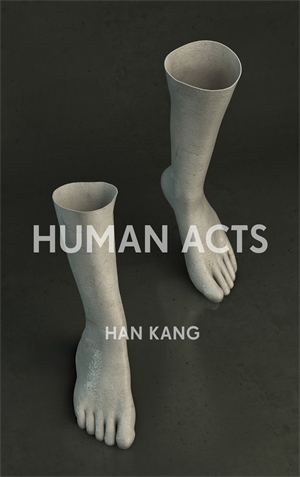

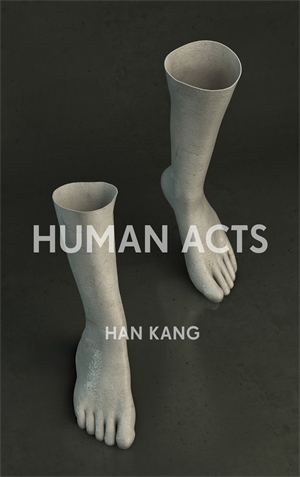

At the weirder end of this Spectrum of Depressing Literature are novelists like Lee Kiho with "At Least We Can Apologize" (2009). At the saner or more cheerful end of spectrum might be authors like Kim Young-ha with "Your Republic is Calling" (2006); or even Hwang Sok-yong with "Princess Bari" (2007). Somewhere in the middle of this Spectrum of Depressing Literature would be Han Kang and "Human Acts" (2016).

If you read English-language articles about books written in the Korean language, all you can read about these days is Han Kang. She's all over the place in English media about books written in the Korean language, obscuring other authors who write in Korean. This is the power of a Man Booker prize. Indeed, an English-only lit fan could be mistaken into thinking that Han Kang represents "Korean literature," as opposed to being simply good literature that happened to have been written in Korean.

Han Kang writes in Korean. Yes. However, that doesn't make her representative of "Korean literature" any more so than you'd call Jonathan Franzen as being representative of "English-language literature" or of even "U.S. literature". Just as there are many faces to both "English-language literature" or "U.S. literature", so, too, are there many aspects to this quasi thing lazily labeled as "Korean literature."

This monotheistic belief in a "Korea" -- there is but one, and we define what it is, whether socially, politically and artistically -- is almost North Korean. It ebbs and flows through many of the South Korean government's pronouncements, as it carefully chooses and selects what "Korean" means. Luckily, the humorous and sharp-eyed among us have labeled this the "national disease" (gukbyeong, 국병), a witty play on the country's time-honored list of national treasures (gugkbo>, 국보) and a disease or an addiction (byeong, 병). Since nationalism rings hollow to anyone under the age of about 40, it's a sneering joke to say that, "You've caught the national disease," meaning that your faux nationalism is a bit gauche and definitely passe.

We saw this in 2012 when comedy pop sensation Psy sent everyone scrambling to get on the bandwagon. He came out with his Whoa!-guys-I-think-we-just-broke-the-internet hit sensation "Gangnam Style." It was the third track on his beautifully named sixth album, "Psy 6 (Six Rules), Part 1," and at around 2.6 billion views and counting on YouTube -- the most, ever -- the Google engineers at YouTube had to re-write their code to handle that modern Macarena that was "Gangnam Style."

We also see this now with Han Kang, a very good author who has sent everyone scrambling to grab her coattails. In their eyes, she is Terra Koreana. In the novelist's eyes, however, she's just a writer. She sees. She feels. She writes. In the vast, vast world that is not-Korean, no one reads Han Kang because she's South Korean or because she writes in the Korean language. We read her because she's good.

In "Human Acts," published in Korean in 2014 and diligently translated into English by Deborah Smith in 2016, Han Kang brings us back to the dictatorship massacring democracy activists in May 1980. It's a heart-wrenching, terrifying novel of sadness, insanity, regret and remorse. A society's pains -- the pains of the people as it claimed democracy for itself -- are laid bare in the author's pages. Readers from recently democratic nations, from Indonesia and the Philippines through to Eastern Europe and Latin America, would certainly have a closer understanding about that which she writes than would a reader from North America.

This second novel of hers in English came out just as her first novel in English, "The Vegetarian," translated in 2015 also by Deborah Smith, was winning the 2016 Man Booker International Prize. This double whammy -- win an international award as your second novel comes out -- is enough to guarantee Han Kang fans for the rest of her career; and, indeed, beyond the grave. Her writing is that good.

Han Kang herself, the child of two successful authors and born in late 1970, lived through the dictatorship massacring democracy activists in May 1980. She was raised in Gwangju. "Human Acts" opens with a grisly scene of the cost of democracy: coffins for the democracy activists are carefully lined up, one grieving cluster of family per dead body.

Using a flexible timeline and creating sections that are both current in May 1980 and memories from later years, Han Kang writes about the legacy of the massacre on various tiers and layers of society: a young volunteer, who is the subject in the Korean-language title of this book "A Boy Comes" or "The Boy's Coming" (소년이 온다), academics, political prisoners, teenagers. Her writing style is, it must be said: unique. By "unique," I mean it can be jarring at times, jumping between first person, second person and third person. The translator, I assume, did a good job here, for it works as an oeuvre. It's not too unnerving after the first few jumps, and readers learn to accept the pattern. As book reviewer Pasha Malla said in the Globe and Mail, "...The book is vivid and troubling, but, like the boom mike dipping into the frame, these technical glitches compromise its poignancy."

On page 202, author Han Kang begins the final chapter of the story: "Epilogue: The Writer, 2013." She explains the prior 200 some odd pages as a process of reconciliation. She was 10-years-old when the dictatorship massacred democracy activists in May 1980. This novel is her coming to terms with that. This novel is her coming to terms with the dark, dark pall that hangs over modern-day South Korea; and in the end, we're healed.

In sum, Han Kang's "Human Acts" gets two thumbs up. It's noire like Scandinavian Noire, it's existential like Kafka or Camus, it's jarring like Gabriel Garcia Marquez or like Haruki Murakami. Do not read her because she's South Korean or because she writes in Korea. Indeed, that's never a reason to read an author. Read her because she's good.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: LTI Korea

gceaves@korea.kr

This pall is the soulless emptiness that comes from a loss of faith in the South Korean Dream. It comes from a lack of trust in the generation born in the 1940s and 1950s and a lack of trust in what they built; in the wealth they crafted out of nothing. The pall comes from a lack of nature, trees and parks all across the country: too many people, not enough greenery. The pall comes from too many humans living in too little space, with no space for the human soul. There's no room to turn at school. There's no space in society for non-mainstream voices. There's no physical space across the nation and no political space within domestic politics to spread your wings and to fly. Add to this a dictatorship massacring democracy activists in May 1980.

Han Kang, born in 1970, grew up in Gwangju and remembers first-hand the massacre of democracy activists in May 1980. Her 2014 novel 'Human Acts' can be seen as a form of national healing for society here, as it comes to terms with the traumas of the past.

This wave of malaise is represented across modern day South Korea through its most representative forms of art: indie music, animation and online comic strips, TV soap opera scripts and, most importantly, literature.

The wave of young South Korean authors who were born in the 1960s, more or less, and who came of age in the 1990s, more or less, are exemplary of this dark wave of depression and lack of faith. They're also some of the best author-psychoanalysts around.

At the weirder end of this Spectrum of Depressing Literature are novelists like Lee Kiho with "At Least We Can Apologize" (2009). At the saner or more cheerful end of spectrum might be authors like Kim Young-ha with "Your Republic is Calling" (2006); or even Hwang Sok-yong with "Princess Bari" (2007). Somewhere in the middle of this Spectrum of Depressing Literature would be Han Kang and "Human Acts" (2016).

If you read English-language articles about books written in the Korean language, all you can read about these days is Han Kang. She's all over the place in English media about books written in the Korean language, obscuring other authors who write in Korean. This is the power of a Man Booker prize. Indeed, an English-only lit fan could be mistaken into thinking that Han Kang represents "Korean literature," as opposed to being simply good literature that happened to have been written in Korean.

Han Kang writes in Korean. Yes. However, that doesn't make her representative of "Korean literature" any more so than you'd call Jonathan Franzen as being representative of "English-language literature" or of even "U.S. literature". Just as there are many faces to both "English-language literature" or "U.S. literature", so, too, are there many aspects to this quasi thing lazily labeled as "Korean literature."

This monotheistic belief in a "Korea" -- there is but one, and we define what it is, whether socially, politically and artistically -- is almost North Korean. It ebbs and flows through many of the South Korean government's pronouncements, as it carefully chooses and selects what "Korean" means. Luckily, the humorous and sharp-eyed among us have labeled this the "national disease" (gukbyeong, 국병), a witty play on the country's time-honored list of national treasures (gugkbo>, 국보) and a disease or an addiction (byeong, 병). Since nationalism rings hollow to anyone under the age of about 40, it's a sneering joke to say that, "You've caught the national disease," meaning that your faux nationalism is a bit gauche and definitely passe.

We saw this in 2012 when comedy pop sensation Psy sent everyone scrambling to get on the bandwagon. He came out with his Whoa!-guys-I-think-we-just-broke-the-internet hit sensation "Gangnam Style." It was the third track on his beautifully named sixth album, "Psy 6 (Six Rules), Part 1," and at around 2.6 billion views and counting on YouTube -- the most, ever -- the Google engineers at YouTube had to re-write their code to handle that modern Macarena that was "Gangnam Style."

We also see this now with Han Kang, a very good author who has sent everyone scrambling to grab her coattails. In their eyes, she is Terra Koreana. In the novelist's eyes, however, she's just a writer. She sees. She feels. She writes. In the vast, vast world that is not-Korean, no one reads Han Kang because she's South Korean or because she writes in the Korean language. We read her because she's good.

'Human Acts' came out in Korean in 2014 and was translated into English by Deborah Smith in 2016. Smith also worked with Han Kang on Han's earlier novel, 'The Vegetarian,' which won a Man Booker International prize just as this second novel was being released in English.

In "Human Acts," published in Korean in 2014 and diligently translated into English by Deborah Smith in 2016, Han Kang brings us back to the dictatorship massacring democracy activists in May 1980. It's a heart-wrenching, terrifying novel of sadness, insanity, regret and remorse. A society's pains -- the pains of the people as it claimed democracy for itself -- are laid bare in the author's pages. Readers from recently democratic nations, from Indonesia and the Philippines through to Eastern Europe and Latin America, would certainly have a closer understanding about that which she writes than would a reader from North America.

This second novel of hers in English came out just as her first novel in English, "The Vegetarian," translated in 2015 also by Deborah Smith, was winning the 2016 Man Booker International Prize. This double whammy -- win an international award as your second novel comes out -- is enough to guarantee Han Kang fans for the rest of her career; and, indeed, beyond the grave. Her writing is that good.

Han Kang herself, the child of two successful authors and born in late 1970, lived through the dictatorship massacring democracy activists in May 1980. She was raised in Gwangju. "Human Acts" opens with a grisly scene of the cost of democracy: coffins for the democracy activists are carefully lined up, one grieving cluster of family per dead body.

Using a flexible timeline and creating sections that are both current in May 1980 and memories from later years, Han Kang writes about the legacy of the massacre on various tiers and layers of society: a young volunteer, who is the subject in the Korean-language title of this book "A Boy Comes" or "The Boy's Coming" (소년이 온다), academics, political prisoners, teenagers. Her writing style is, it must be said: unique. By "unique," I mean it can be jarring at times, jumping between first person, second person and third person. The translator, I assume, did a good job here, for it works as an oeuvre. It's not too unnerving after the first few jumps, and readers learn to accept the pattern. As book reviewer Pasha Malla said in the Globe and Mail, "...The book is vivid and troubling, but, like the boom mike dipping into the frame, these technical glitches compromise its poignancy."

On page 202, author Han Kang begins the final chapter of the story: "Epilogue: The Writer, 2013." She explains the prior 200 some odd pages as a process of reconciliation. She was 10-years-old when the dictatorship massacred democracy activists in May 1980. This novel is her coming to terms with that. This novel is her coming to terms with the dark, dark pall that hangs over modern-day South Korea; and in the end, we're healed.

In sum, Han Kang's "Human Acts" gets two thumbs up. It's noire like Scandinavian Noire, it's existential like Kafka or Camus, it's jarring like Gabriel Garcia Marquez or like Haruki Murakami. Do not read her because she's South Korean or because she writes in Korea. Indeed, that's never a reason to read an author. Read her because she's good.

By Gregory C. Eaves

Korea.net Staff Writer

Photos: LTI Korea

gceaves@korea.kr