-

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel- NEWS FOCUS

- ABOUT KOREA

- EVENTS

- RESOURCES

- GOVERNMENT

- ABOUT US

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

|

Culture review section of Monthly KOREA’s Feb 2020 issue▶ Link to Webzine |

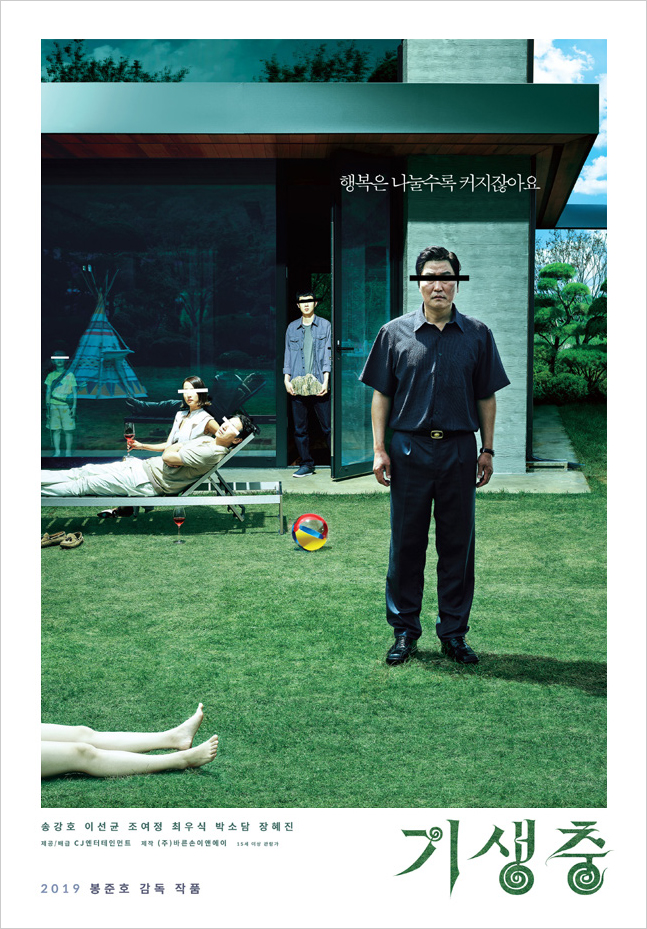

Why the World Loves This Film

Director Bong Joon-ho’s “Parasite” has achieved cinematic immortality by winning four Academy Awards and becoming the highest-grossing Korean movie of all time. After the movie received a staggering six Oscar nominations, most involved with the film would have been content to have walked away with just one gold statuette. To earn four — including a historic first Best Picture award for a non-English language film — was nothing short of a total shock. But to anyone who has seen it, this remarkable film leaves no doubt that its accolades were well deserved.

Written by Tim Alper

On a glittering night for Korean cinema in Los Angeles, Bong Joon-ho’s tour de force “Parasite” picked up not only the biggest Oscar — Best Picture — but also those for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay and Best International Feature Film.

The auteur beat two of Hollywood’s biggest directors to earn his much-coveted prizes: impresario Quentin Tarentino (“Once Upon a Time in Hollywood”) and one of America’s best and most celebrated filmmakers, the inimitable Martin Scorsese (“The Irishman”).

The Oscars are just icing on the cake of what has been a veritable slew of international awards for “Parasite,” beginning most notably last year with the Palme d’Or, the top prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

Powerful Speech

Director Bong Joon-ho raises the Best Director Oscar his film “Parasite” won at the 92nd Academy Awards in Los Angeles. © Yonhap News

The film’s cast also picked up the best ensemble prize at the Screen Actors Guild Awards. The audience gave the Korean actors a standing ovation, and Bong delivered a powerful acceptance speech in telling the non-Korean audience, “Once you overcome the one-inch-tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing Korean films.”

Indeed, it seems like “Parasite” being set in Korea and featuring an all-Korean cast with an entirely Korean script failed to deter international audiences. Instead, the world has been totally engrossed by it. The film is one of the first Korean movies to receive a general release at mainstream cinemas in major markets like the U.K., Brazil and Italy.

But what did this movie do that no other foreign-language film pulled off in the Oscars’ 92-year history?

And how did “Parasite” do the seemingly impossible: overcome the previously insurmountable “one-inch” barrier that kept Korea’s “fantastic” films out of reach for global moviegoers?

Universal Theme

The cast of “Parasite” pose with the four Oscars their film won at the 92nd Academy Awards in Los Angeles. © Yonhap News

Much has been made of the non-specific dark comedic elements in “Parasite” that has delighted international critics. But black comedy is usually very subtle and always highly subjective. On its own, humor like this cannot hope to win over global audiences.

Other screenwriters, meanwhile, have spoken in glowing terms about how the film provides a biting critique of Korean society. But since most of the movie’s non-Korean viewers have probably never been to Korea, this also is unlikely to have sparked the film’s international success.

So if neither of the above sent “Parasite” on the path to success, what did?

For starters, the film is full of imagery that transcends cultural boundaries to the extent that viewers around the world can relate to it easily. Its imagery does not require much knowledge of the intricacies of Korean life, culture or philosophy.

At its heart, “Parasite” is about the way rich and poor folk try to relate to one another. As it indicates at every step through careful framing, plot devices and understated metaphor, the classes simply cannot meet in the middle — no matter how hard they try — as they never find themselves on a level playing field.

The rich family lives at or above ground level and is constantly shown climbing stairs, ascending to new heights. They cannot truly descend into the subterranean world below that the poor family lives most of its life in.

In one key scene, a rich character complains that he cannot bear the smell of people who ride the subway, and thus avoids mass transit in favor of a chauffeur-driven car.

The poor family, meanwhile, lives the majority of the time just below ground level, in a semi-submerged apartment type called banjiha (half basement) in Korean.

When poor characters are scared or need to avoid the wrath of the rich, their natural instinct drives them lower, almost as if they are safe in the knowledge that the deeper they venture below ground level, the less likely the rich will find them.

The poor characters in Emir Kusturica’s 1995 masterpiece “Underground,” also a Palme d’Or winner, behave in the same way. When they feel threatened, they retreat to a vast cellar where corrupt authorities would never dare look for them, no matter how outrageously they behave down there.

This kind of imagery speaks volumes to people all over the world. The penthouse is forever the turf of the rich, while the cramped and dark recesses of subterranean cities house the humblest and the most secretive hovels of the poor.

‘Upstairs, Downstairs’

Several Western movies and dramas have made use of this very same filmic device that drives the upper class to physical heights and the oppressed to cramped, low-level spaces. Some going this route have often done so to a similarly captivating effect.

The British TV drama “Upstairs, Downstairs,” which ran from 1971-75 (and was revived from 2010-12), and “Downtown Abbey” (2010-15) are prime examples of rich families living upstairs who are served by staff who reside below.

But just like “Parasite,” the rich and the poor simply cannot stay apart no matter how hard they try. The world of the upper class above inevitably spills below, and the goings-on of the low-dwelling poor always burst upwards.

This is what makes “Parasite” so appealing to so many audiences.

Whereas so many Korean films explore uniquely Korean themes, “Parasite” tells a universal and timeless story, one that international audiences can relate to. The plot will continue to captivate filmgoers, who will inevitably want to see what the fuss is about.

The dozens of awards lavished on this deeply thought-provoking film are only the beginning. The real “Parasite” journey has just begun because its irrepressible message only really begins when the movie ends.

As future generations inevitably continue to engage with this highly decorated and history-making movie, “Parasite” will continue getting under the skin — and into the minds — of generations of moviegoers worldwide.

Most popular

- First hearing-impaired K-pop act hopes for 'barrier-free world'

- 'Mad Max' director impressed by 'cinema-literate' Korean viewers

- Romanian presidential couple visits national cemetery

- 'Korean mythology is just as wonderful as Greek and Roman'

- Hit drama 'Beef' wins awards from 3 major Hollywood guilds