-

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel

Korea.net's 24-hour YouTube channel- NEWS FOCUS

- ABOUT KOREA

- EVENTS

- RESOURCES

- GOVERNMENT

- ABOUT US

- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

|

Monthly KOREA’s August 2019 issue. ▶ Link to Webzine |

Flame-inspired Drawings

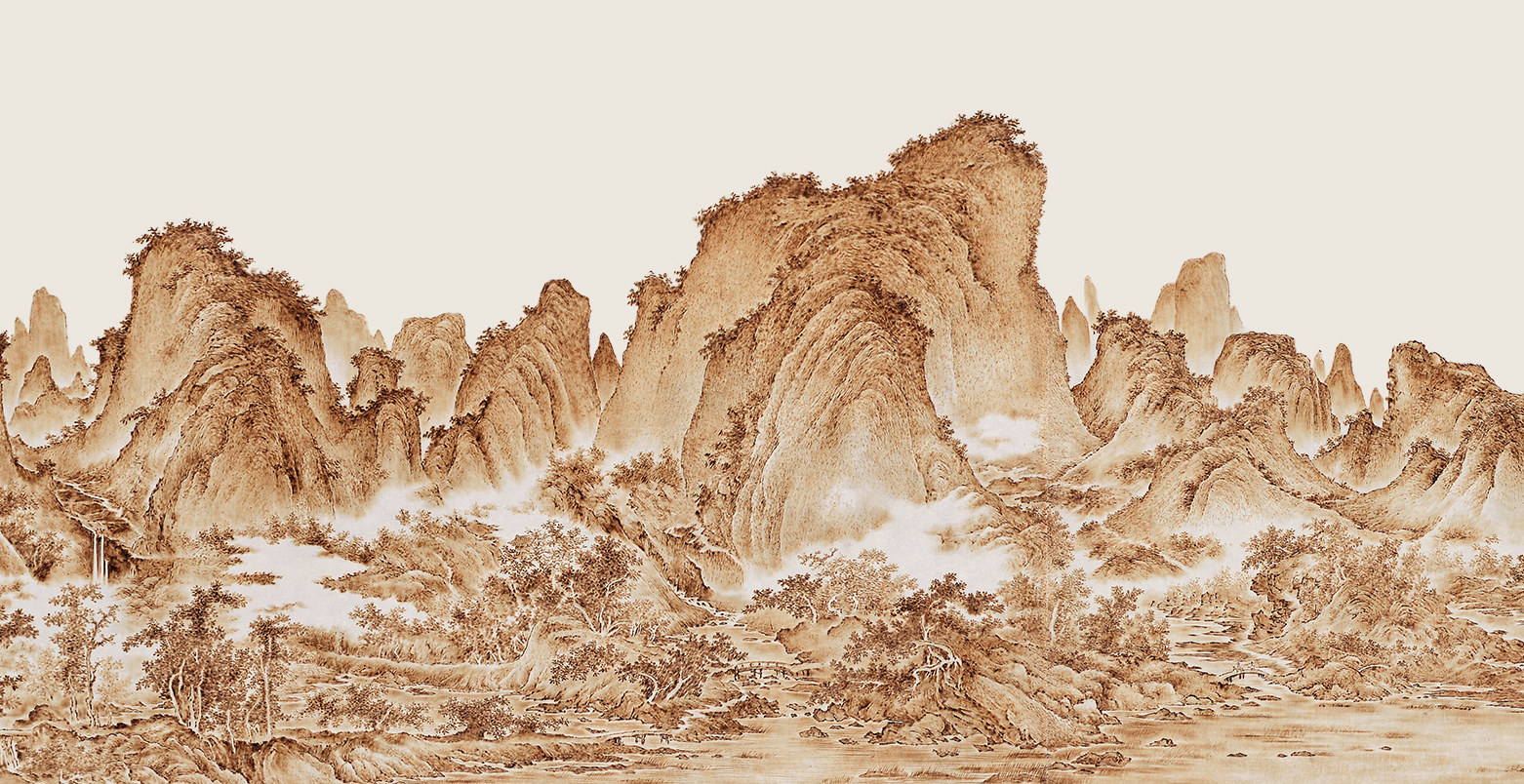

Sumukhwa (traditional ink-based painting) and nakhwa (Korean pyrography) share the same fundamentals but are separate genres of art. While the former utilizes the nature of paper to absorb water and has a long history as a widely known art, the latter focuses on paper’s flammable properties and is known to a minority due to a far shorter history. Nakhwa’s value to Korean art is indisputable, however, given its designation as an Intangible Cultural Heritage.

Written by Kim Samuel , Photographed by Studio Kenn

Nakhwa is a type of pyrography through which a painting is produced using a soldering iron on a canvas made of paper, silk, wood or leather, with the nicknames “iron painting” and “fire painting.” This art form almost went extinct until its artistic value was recognized in 2010, when nakhwa master Kim Youngjo was designated Intangible Cultural Heritage No. 22 of Chungcheongbukdo Province. In January this year, nakhwajang (wood burning technique) saw a huge boost in public awareness after being named National Intangible Cultural Heritage No. 136.

When nakhwa first came to Korea remains unclear but according to historical records, it is assumed to have come from China and blossomed during the mid to late Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). Geunyeokseohwajing (A Collection of Korea’s Paintings and Calligraphic Works), published by Oh Se-chang in 1928, contains records that a Jang of Andong, who was the biggest writer and artist of the time along with Sin Saimdang, was proficient in nakhwa. Based on this observation, the art form is believed to have been developed by women using a soldering iron normally utilized for housework. Park Chang-gyu, perhaps the most important figure in nakhwa, paved the way for this genre. Particularly skilled at nakjuk, a drawing on bamboo with iron, he further developed this technique on paper in 1837, which further solidified nakhwa’s lofty status in the Korean art world.

Nakhwa master Kim Youngjo starts a new work.

A soldering iron, too heavy to be used alone, requires a special tool to lift.

Fiery Energy

Nakhwa is similar to ink painting except the drawing tool is a soldering iron instead of a brush. The iron is seared with charcoal and its surface smoothened with traditional sandpaper made from straw rope. When dust is removed from the tool and the temperature is set, the artist can start drawing on a canvas such as Hanji (traditional Korean paper). The texture stroke of nakhwa is similar to that of ink painting including the bubyeokjun stroke, which is used to describe the rough textures of mountains or rocks using the flat side of the brush, and the woojeomjun stroke used for stipple painting with the pointy brush tip. The speed, temperature and pressure of the iron determine lightness and shade. Since any mark the iron makes is non-erasable, doing nakhwa properly requires intense focus and attention to detail.

In nakhwa, the shading typically created with black ink is replaced with burned brown shading for a more robust look and embracing the flame’s fiery energy. nakhwa’s artistic appeal was illustrated in a few Joseon records. For example, King Heonjong (1827-49) described the dragon on his cigarette pipe this way: “The scales seem alive.” And leading Joseon scholar Kim Jeong-hee also held nothing back in praising nakhwa technique.

Any flammable material can be used to create a wide range of themes for nakhwa like landscapes, flowers, birds, portraits, Buddhism and folk subjects. The versatility of this genre vaguely placed its classification between craft and painting, but its status has been solidified as a traditional style of painting thanks to its designation as a National Cultural Heritage.

These Starbucks tumblers and cups feature nakhwa designs.

Most popular

- First hearing-impaired K-pop act hopes for 'barrier-free world'

- 'Mad Max' director impressed by 'cinema-literate' Korean viewers

- Romanian presidential couple visits national cemetery

- President Yoon, Japan PM pledge better trilateral ties with US

- President, Romania pledge better defense, nuclear power ties