- 한국어

- English

- 日本語

- 中文

- العربية

- Español

- Français

- Deutsch

- Pусский

- Tiếng Việt

- Indonesian

|

Monthly KOREA’s April 2020 issue. ▶Link to Webzine |

Hansik in Media

The 2003 hit TV drama “Jewel in the Palace” stirred up culinary interest in the royal cuisine of the Joseon Dynasty. A booklet of recipes for about 70 royal dishes featured in the drama was published in both English and Korean, attesting to the historical series’ long-lasting popularity. Another blockbuster drama, “My Love From the Star,” left in its wake throngs of Korea-bound tourists on the quest for chimaek (a portmanteau of the terms “chicken” and “beer”), and “Parasite” (2019) drew global interest to Korean casual dining with a simple noodle dish.

Written by Lee Herim, food writer

An estimated 4,500 Chinese tourists in 2016 held a chimaek (chicken and beer) party on Wolmido Island off the coast of Incheon. © Yonhap News

Serving of Culture

When “Parasite” (2019) won four Oscars, my mind was filled with sliders (mini burgers) from the 2005 Hollywood film “Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle.” Starring Korean American actor John Cho as Harold and Indian American actor Kal Penn as Kumar, this road movie was set at a New Jersey branch of the fast-food chain White Castle.

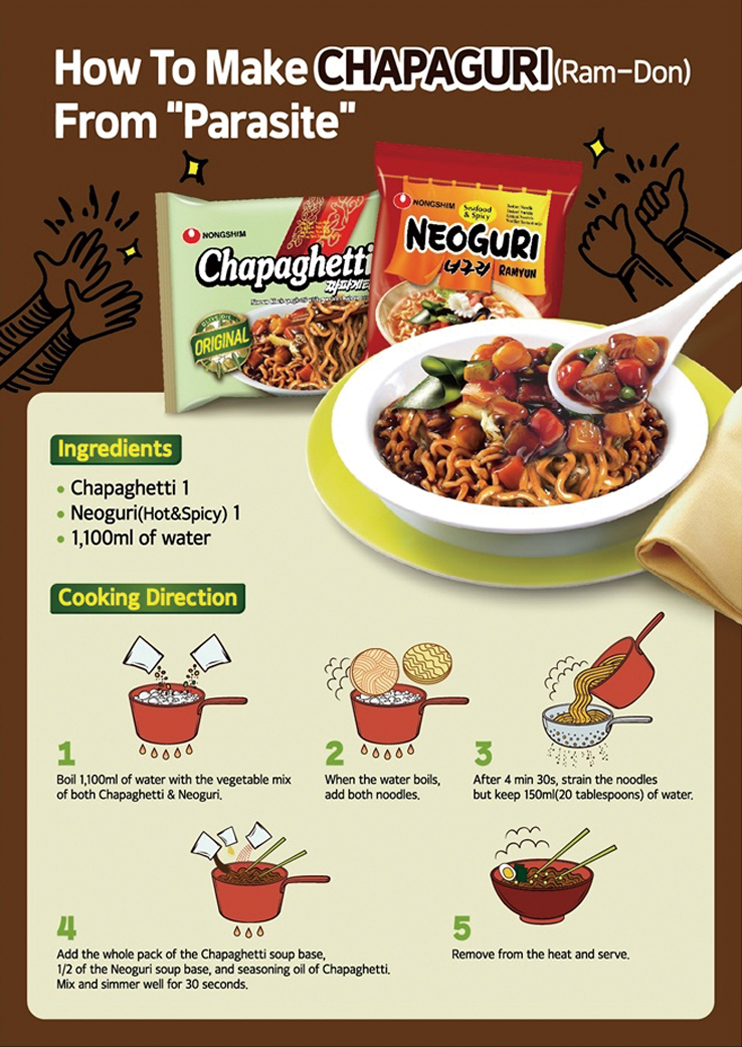

A global frenzy erupted over “Parasite” after the latter’s historic Oscar wins, with such fervor spilling over onto the “ramdon,” a noodle dish whose name is portmanteau of the words “ramyeon (instant noodles)” and “udon (thick wheat-flour noodles)” featured in the movie. Nongshim, the manufacturer of Chapagetti and Neoguri, two packaged noodle products comprising the mainstay of ramdon, promptly distributed multilingual recipes of the dish. In global hubs like London, New York and Tokyo, restaurants produced their own takes of the film’s sirloin ramdon.

The global popularity of “Parasite” led to translations of recipes of “ramdon,” a cross between Korean instant and long wheat-flour noodle dishes, in 11 languages. © Nongshim

Ramdon grew popular among netizens in 2009 after being featured in the reality TV show “Dad! Where Are We Going?” in 2013. This launched a nationwide trend of the fusion of Chapagetti and Neoguri. The humble mix of instant noodles, sure to whet the appetites of people across social classes, was a nondiscriminatory food choice, until “Parasite” director Bong Joon-ho introduced the idea of complementing the noodles with sirloin, a pricey food in Korea. The socioeconomic vanity of the film’s rich family is manifest in ramdon served with the meat.

Sliders in “Harold and Kumar” offer a similar metaphor. The White Castle branch in central Manhattan is dingy and probably grimy, too, and their sliders aren’t any better. The artificial flavor and aroma plus the brittle texture of the sliders are a disappointment at best. Customers there are more similar to the poor family in “Parasite” than the rich family. I began to realize why the film’s main characters, one born to an immigrant family headed by a white-collar worker and the other also to an immigrant family headed by a doctor, were fixated on White Castle as their destination. Undercutting the film’s rogue jokes and jabs at the racism and social inequity of American society is the bitter irony in the characters’ quest to reach White Castle. With a heavy heart, I watched the two lead characters merrily wolf down sliders. Afterwards, I’d spot White Castle sliders every now and then with dirt-cheap price tags in the frozen aisles of New York supermarkets.

Korean-style fried chicken is a globally recognized Hansik. © shutterstock

Conduit for Cultural Exchange

The English subtitles for “Parasite,” as well as those for other languages that stemmed from the English, employ the portmanteau “ramdon” to indicate the use of the Korean terms ramyeon and udon. Listening to the translator explain his intent to capture the implications of the products Chapagetti and Neoguri, I remembered that had Korean subtitles dubbed White Castle sliders “school-store hamburgers,” I would’ve never wasted my time at the fast-food joint during my limited time in Manhattan.

Understanding a language entails understanding the culture of the language’s home country. On the other hand, the ramdon from “Parasite” is an intuitive storytelling device. Topping off a mixture of two noodle types with expensive meat creates a dish representing the unlikely mingling of two families that are seemingly similar yet a world apart from each other. The metaphor for fusion also applies to Hansik. Rather than remaining static, Hansik continues to evolve in flexibly adapting to modern influences and variations.

Korean films and drama series are featuring a wider spectrum of Hansik, from traditional to modern variants. © pixta

Korea’s campaign to spread Hallyu worldwide first used to champion the promotion of kimchi abroad. © shutterstock

Even a cursory search for ramyeon on YouTube will result in a slew of inventive creations. The rise of eating streamers — and especially buldak bokkeum myeon (super spicy chicken fried noodles) — has put ramyeon at the forefront of an internet-fueled phenomena.

The campaign to spread Hallyu worldwide first used to champion the promotion of kimchi abroad. Today, many around the globe are well aware that Hansik comprises far more than just a spicy condiment. Even the most casual Korean fare is beloved by fans abroad, from specialty fried or seasoned chicken with a variety of sauces to instant ramyeon concoctions. As Korea’s culinary ambassador to the world, Hansik is seeing an ever-growing presence on the world stage.